Ötzi the Iceman is one of the most well-studied individuals in human history, but there always seems to be more to learn about him. A new genomic study has now found that he didn’t look the way previous studies had imagined him – instead he was bald, his skin was darker, and he had an ancestry that was far more exotic and isolated than previously thought.

In September 1991, two hikers discovered a human body in the Alps near the Austria and Italy border. At first they assumed they’d stumbled on an unlucky modern mountaineer, but on closer, scientific investigation, it was determined that the chap had died about 5,300 years ago. In the three decades since his discovery, Ötzi has been studied extensively, with scientists able to figure out what he ate, how he dressed, how he lived and how he died.

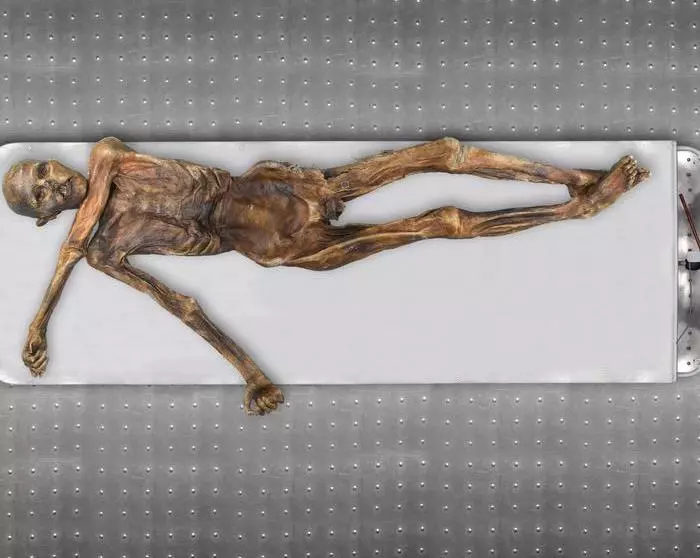

His full genome was published in 2012, allowing scientists to reconstruct an image of what he might have looked like. From that data, Ötzi was imagined as a fairly light-skinned man with a bushy beard, a thick head of unkempt hair, deep-set eyes and wrinkled skin beyond his 45 years of life. But a new study, using more comprehensive genomic analysis techniques, upends much of that picture.

The updated description indicates Ötzi had darker skin than modern Europeans, and had gene variations that suggested male pattern baldness. This would explain why no head hair was discovered along with the body – previous studies had presumed that the hair had just been lost to time. His genetics also predisposed him to type 2 diabetes and obesity, although it was unlikely those would have been a problem for him living in a time before fast food and desk jobs.

“The genome analysis revealed phenotypic traits such as high skin pigmentation, dark eye color, and male pattern baldness that are in stark contrast to the previous reconstructions that show a light-skinned, light-eyed, and quite hairy male,” said Johannes Krause, lead author of the study. “The mummy itself, however, is dark and has no hair.”

But the most surprising finding was Ötzi’s ancestry. The team found that about 90% of the Iceman’s ancestry came from early Neolithic farmers from Anatolia, a region in west Asia that contains much of modern-day Turkey. Western hunter-gatherers comprise the remaining portion, but there was no trace of genes from eastern Steppe Herders, which were reported in the 2012 genomic study.

“We were very surprised to find no traces of Eastern European Steppe Herders in the most recent analysis of the Iceman genome; the proportion of hunter-gatherer genes in Ötzi’s genome is also very low,” said Krause. “Genetically, his ancestors seem to have arrived directly from Anatolia without mixing with hunter gatherer groups.”

The team attributes this earlier mix-up to contamination by modern DNA, as well as advances in sequencing technology and a more detailed library of ancient genomes to compare Ötzi to. No doubt this famous mummy will continue to be studied for further insights into the early peoples of Europe.

The research was published in the journal Cell Genomics.

Source: Max Planck Institute