In what many of us would consider a true public service to one of the world's best food groups, scientists have flicked the switch on a mechanism that causes cold-stored potatoes to produce the carcinogen acrylamide. Growing these genetically tinkered potatoes could eradicate known cancer risks associated with darkened chips, making them much healthier regardless of processing.

"This discovery represents a significant advancement in our understanding of potato development and its implications for food quality and health,” said Jiming Jiang, a Research Foundation Professor at Michigan State University (MSU). “It has the potential to affect every single bag of potato chips around the world.”

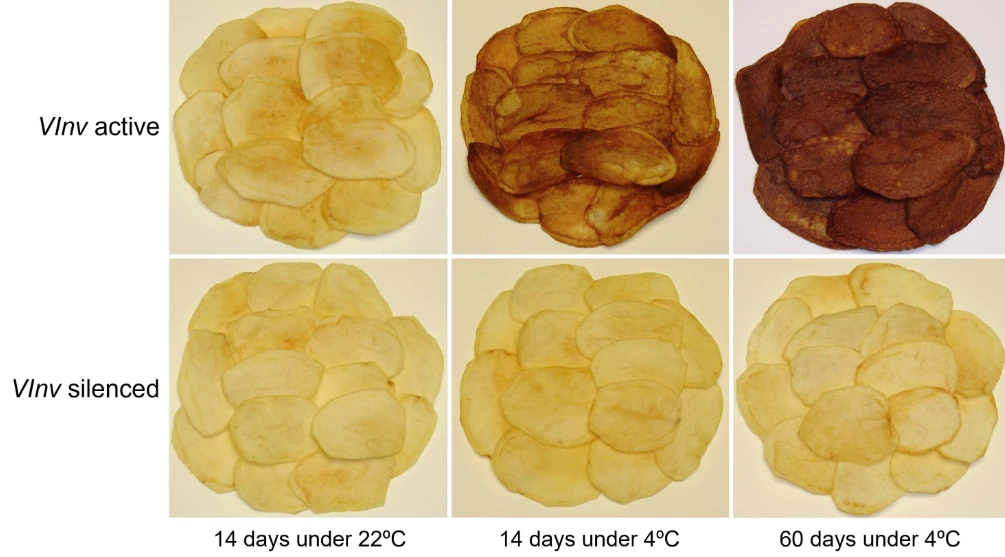

The US potato industry brings in US$240 million annually, and demand for taters in all their wonderful processed shapes and sizes is year-round. As such, a certain amount of stock in season is sent to cold storage to supply the demand. However, thanks to a normal biological function in the root vegetable, low temperatures trigger a mechanism that converts starches to sugars. When processed, these tubers that have experienced cold-induced sweetening (CIS) appear darker when cooked.

Unfortunately, it's more than potato-skin deep, as this darkened chip is a crispy red flag – it indicates elevated levels of acrylamide, a chemical that has been associated with increased cancer risk due to its carcinogenic properties.

The good news? MSU scientists doing God's work, Jiang and David Douches have found a way to get to the root of the problem, identifying the gene that regulates the temperature-driven 'on' switch for sugar conversion. It means that potatoes grown with their potato vacuolar invertase gene, or VInv, inhibited could be cold-stored without the need to address potential acrylamide accumulation during cooking – something that could also save time and money for producers. The finished golden-fried chip is also much more appealing to consumers.

“We’ve identified the specific gene responsible for CIS and, more importantly, we’ve uncovered the regulatory element that switches it on under cold temperatures,” explained Jiang, who has had the rather enviable career of working with spuds for more than two decades. “By studying how this gene turns on and off, we open up the possibility of developing potatoes that are naturally resistant to CIS and, therefore, will not produce toxic compounds.”

What's more, the scientists say this is not some potato pie in the sky idea; producing this 'healthier' spud is in the near future, with the team now looking at breeding techniques in the greenhouses of Douches, who runs MSU's potato breeding and genetics program.

“All our facilities are on campus so the research work can be done efficiently,” Douches said. “With our collaboration, we were able to produce a finding that paves the way for targeted genetic modification approaches to create cold-resistant potato varieties.”

The study was published in the journal The Plant Cell.

Source: MSU