A German research team has prototyped an extraordinary heating/cooling system that stresses and unloads nickel-titanium "muscle wires" to create heated and cooled air at twice the efficiency of a heat pump or three times the efficiency of an air conditioner. Crucially, the device also uses no refrigerant gases, meaning it's a much more environmentally friendly way to heat or cool a space.

The device is based on a peculiar property of certain shape-memory metal alloys that spring back into shape after being deformed. In some cases – particularly with nickel-titanium, also known as nitinol – these metals absorb significant amounts of heat when they're bent out of shape, and then release that heat when they're allowed to revert to their normal shape. The difference between the loaded wire and the released wire can be as much as 20° C (36° F).

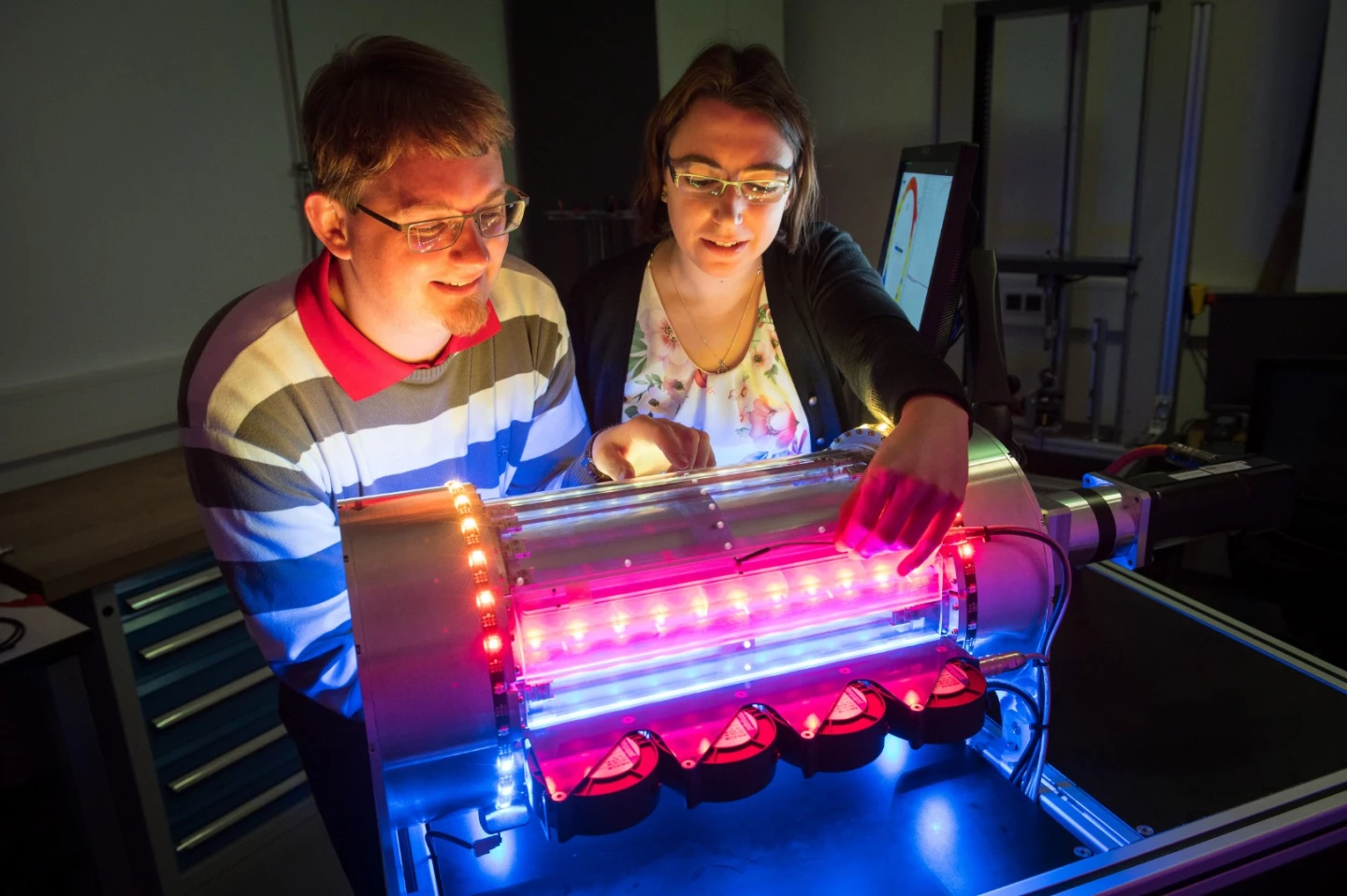

The cooling device is thus quite simple in concept. It uses a rotating cylinder covered in nitinol wire bundles. The wires are loaded up as they pass through one side, sucking heat out of the air and storing it up. Then as they rotate past the other side, they're allowed to snap back into shape, dumping the heat on the second side. Air is blown through chambers on each side, giving you one feed of heated air and another feed of cool air.

The Saarland University team has been experimenting with the device to figure out the optimal convergence of wire loading, rotational speed, and how many wires should be in a bundle to create the biggest possible heat differential between the two sides from a given energy input.

And the results seem very exciting. The Saarland University team claims that "the heating or cooling power of the system is up to thirty times greater than the mechanical power required to load and unload the alloy wire bundles" depending on the type of alloy used. They say that this makes their new system more than twice as good as a conventional heat pump and three times as good as a conventional refrigerator.

"Our new technology is also environmentally friendly and does not harm the climate, as the heat transfer mechanism does not use liquids or vapors," says Professor Stefan Seelecke, the university's Chairman of Intelligent Metal Systems. "So the air in an air-conditioning system can be cooled directly without the need for an intermediate heat exchanger, and we don't have to use leak-free, high-pressure piping."

The idea of achieving an air cooling or heating effect simply by bending and unbending little pieces of metal sounds bizarre. What about metal fatigue? How long will those alloy wires last in these variable temperature environments before they get brittle and break off?

Well, that's one area where nitinol is very different from other metals. Indeed, it's most famous for its use in medical devices, particularly implantable ones such as stents, where its remarkable flexibility allows a stent to bend, crush, stretch and twist with the artery as the body moves.

Verdict Medical Devices summed up nitinol's fatigue properties thus: "it is by far the most resistant metal known to high-amplitude strain-controlled fatigue environments. Several applications … employ nitinol solely because of its extraordinary fatigue resistance."

The cooling device described above would appear to fit the description of a high-amplitude, strain-controlled application. But, of course, it'll be up to the researchers, or a future commercial team, to demonstrate how long you can expect your nitinol reverse cycle air conditioner to last.

It certainly looks like an exciting piece of technology, with the capability to reduce energy use in heating/cooling as well as taking refrigerant gases out of the equation.

Source: Saarland University