Modern Mars is a barren world, drier than any desert on Earth. But geological evidence shows that this wasn’t always the case – in the distant past the Red Planet had flowing water. It’s long been thought that ancient Mars was warm and wet, but a new study has found evidence that it was instead covered in ice sheets, and much of its water was glacier run-off.

There’s no shortage of evidence that Mars was once much wetter than it is today. Between orbiters in the sky and rovers on the ground, we’ve seen signs of ancient oceans, shorelines, lakes, rivers and flood plains.

All of this has led scientists to hypothesize that Mars used to be far more Earth-like, with a warm, temperate climate and regular rainfall. But now a new study, from researchers at the University of British Columbia, has found that this story doesn’t account for all of the structures seen.

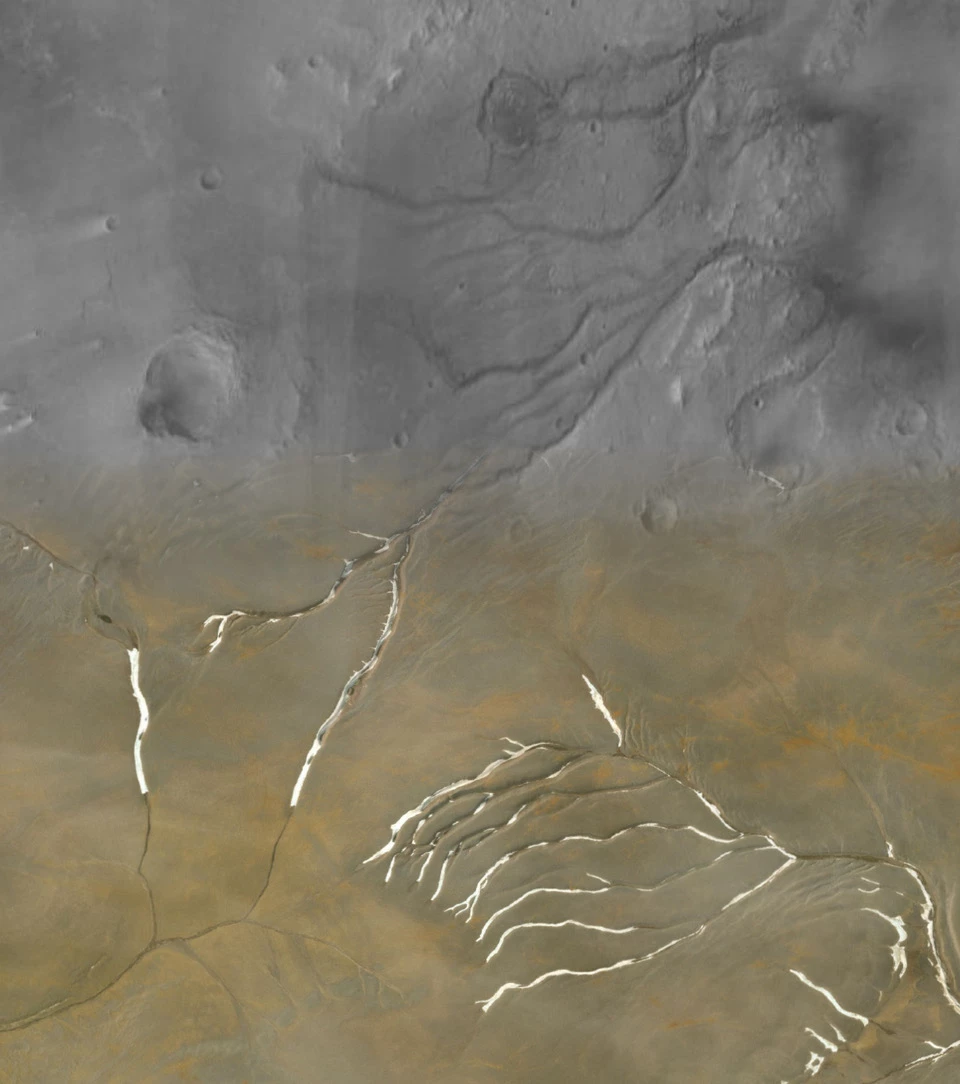

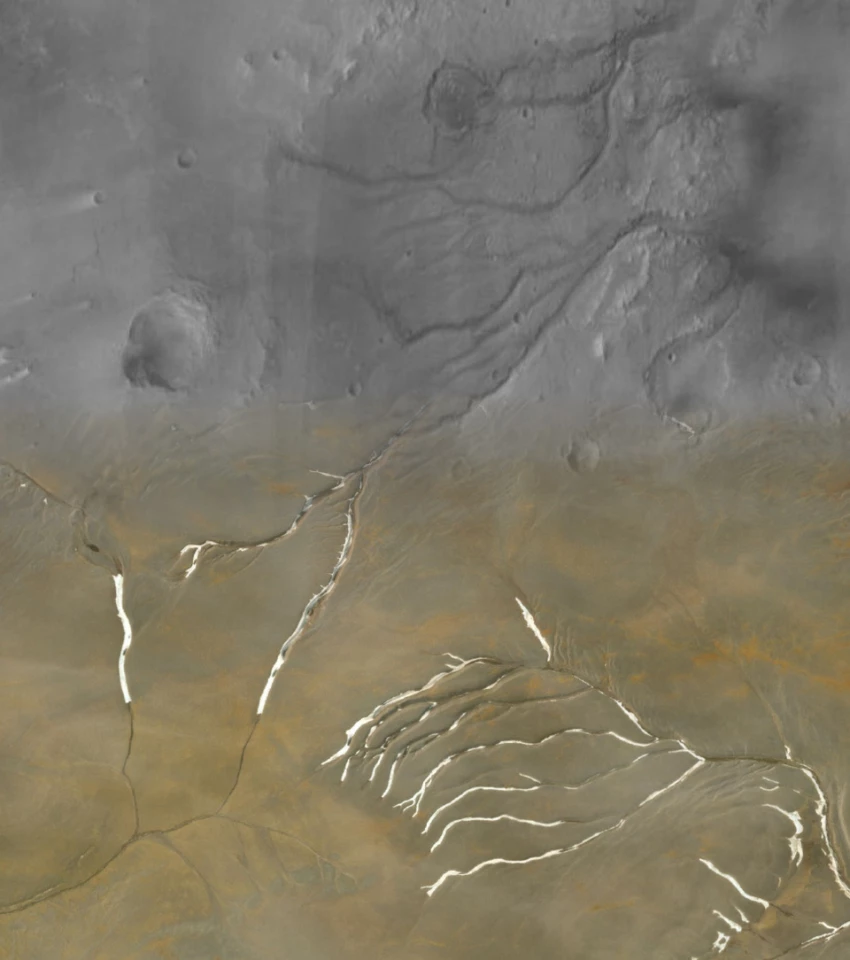

“For the last 40 years, since Mars’s valleys were first discovered, the assumption was that rivers once flowed on Mars, eroding and originating all of these valleys,” says Anna Grau Galofre, lead author of the study. “But there are hundreds of valleys on Mars, and they look very different from each other. If you look at Earth from a satellite you see a lot of valleys: some of them made by rivers, some made by glaciers, some made by other processes, and each type has a distinctive shape. Mars is similar, in that valleys look very different from each other, suggesting that many processes were at play to carve them.”

To investigate, the researchers used an algorithm that studies the shape of valleys and figures out the erosion process that most likely created them. The team put this algorithm to work analyzing over 10,000 Martian valleys.

The researchers found that only a fraction of the valley networks studied match the patterns expected of surface water erosion. Instead, many of the others resembled run-off channels that form underneath glaciers, as meltwater drains away.

This scenario also helps plug a major plot hole in the previous warm-and-wet hypothesis. At the time these channels formed – around 3.8 billion years ago – the Sun was much quieter, and Mars’ climate should have been very cold.

“Climate modeling predicts that Mars’ ancient climate was much cooler during the time of valley network formation,” says Grau Galofre. “We tried to put everything together and bring up a hypothesis that hadn’t really been considered: that channels and valleys networks can form under ice sheets, as part of the drainage system that forms naturally under an ice sheet when there’s water accumulated at the base.”

The idea that Mars was mostly icy and not a warm paradise might seem to pour cold water (so to speak) on the chances of ancient life on the Red Planet – but the team says the opposite is true. They say the ice sheet would have stabilized the water supply, and could have protected any life from solar radiation. That’s a job our magnetic field does well, but Mars is lacking such protection.

The research was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Source: University of British Columbia