For over a year, NASA's Curiosity Mars Rover has been investigating the clay-bearing unit in the Gale Crater. Now the space agency has announced that the intrepid explorer is on the move again, starting a summer-long journey to a higher part of Mount Sharp dubbed the "sulfate-bearing unit."

The Curiosity Mars Rover has been on the Red Planet since 2012, but only reached its primary destination of Mount Sharp in the 96-mile-wide (154-km) Gale Crater two years later. Since early 2019, the unmanned explorer has been investigating a region called the clay-bearing unit. And by May, it had analyzed drilled samples and found them to contain the highest amounts of clay minerals found on Mars up until that point.

It later caused some excitement among scientists when a large methane spike of around 21 parts per billion was detected, and then baffled researchers by revealing huge seasonal changes in oxygen levels.

Back in March of this year, the mission team sent Curiosity up a steep slope at the northern end of a slope with a sandstone top called the Greenheugh Pediment to take a look at the terrain they'll encounter later in the mission. Near the top, the rover discovered nodules which suggest that there was water in the crater longer after ancient lakes had gone.

"Nodules like these require water in order to form," pediment detour lead Alexander Bryk said. "We found some in the windblown sandstone on top of the pediment and some just below the pediment. At some point after the pediment formed, water seems to have returned, altering the rock as it flowed through it."

If life was ever present in this region of Mars, the discovery of the nodules extends the period for when conditions might have been right to support it.

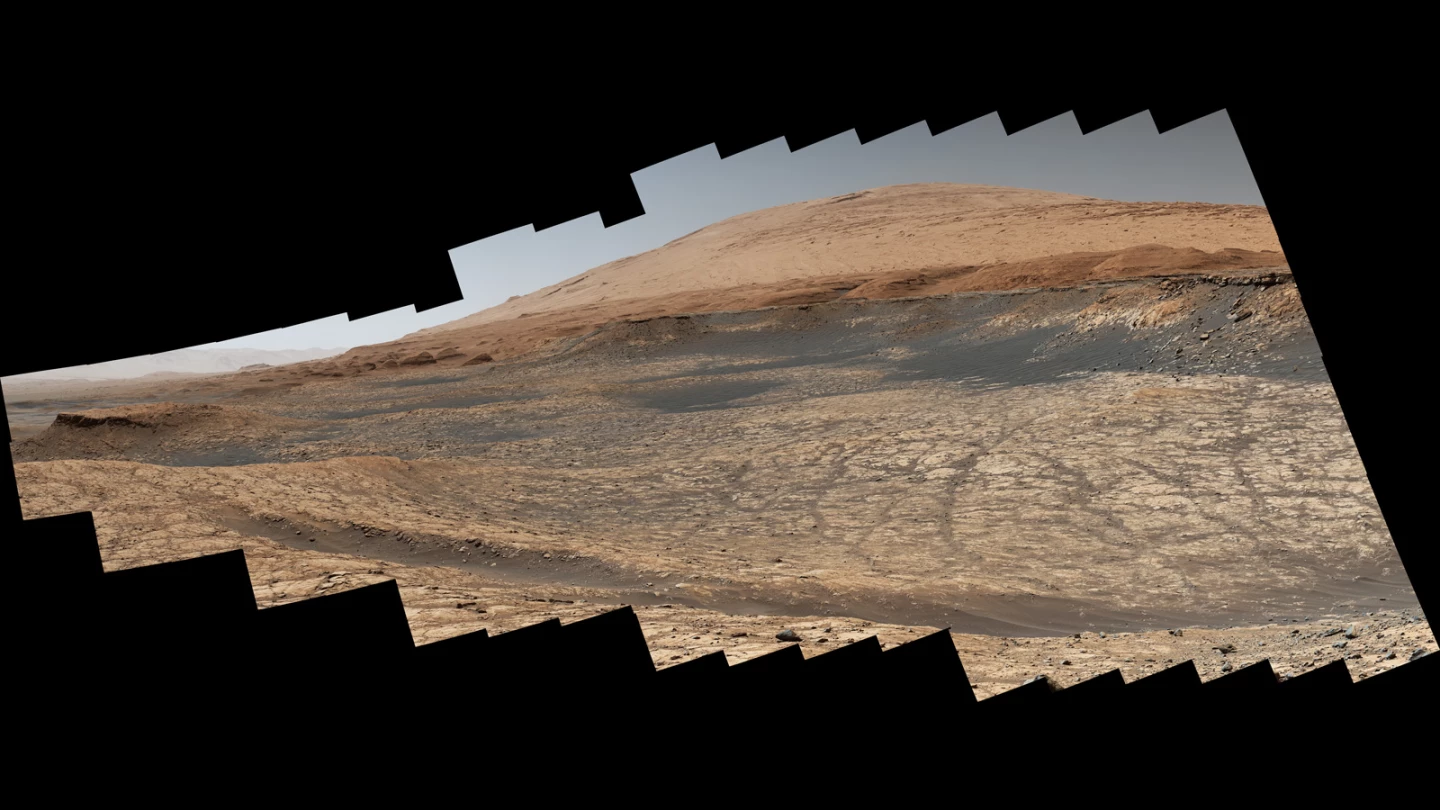

Curiosity has also found time to snap a number of impressive panoramas, and has just taken another to mark the start of its mile-long journey around an area of deep sand to get to its next stop on its seven-year mission – an area of Mount Sharp dubbed the sulfate-bearing unit.

Sulfates are known to form around water as it evaporates, so scientists are hoping that the new region will offer up clues about how the climate changed nearly 3 billion years ago.

The mission team expects the rover's top speed will fall somewhere between 82 and 328 feet (25-100 m) per hour, and for some of the journey, Curiosity will drive itself.

"Curiosity can't drive entirely without humans in the loop," said lead rover driver Matt Glidner who, like other members of the mission team, is working remotely from home due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. "But it does have the ability to make simple decisions along the way to avoid large rocks or risky terrain. It stops if it doesn't have enough information to complete a drive on its own."

It is hoped that Curiosity will reach its new destination by our early (northern) fall, though there may be stops along the way for the odd drilling opportunity if something interesting presents itself.

Source: NASA