The James Webb Space Telescope has been used to confirm the existence of an exoplanet for the first time. Known as LHS 475 b, this Earth-sized world is a cosmic stone’s-throw away and is likely the first of many planet discoveries by Webb.

Over 5,000 exoplanets – worlds that orbit a star other than the Sun – have been discovered to date, but that number could soon skyrocket thanks to James Webb’s more sensitive instruments. To test out its power, a team of astronomers pointed it at a star system where another telescope, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), had previously spotted evidence of a planet.

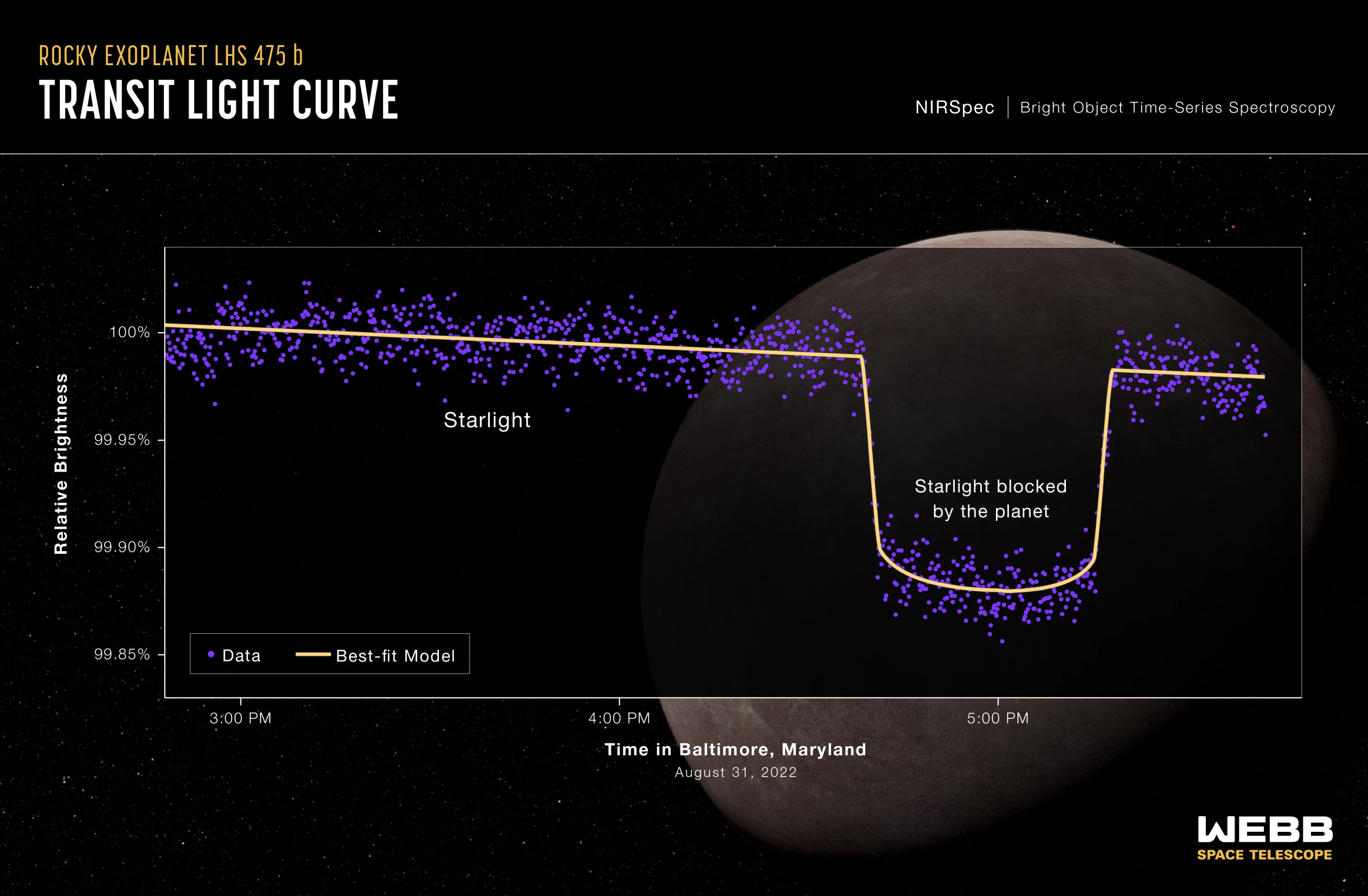

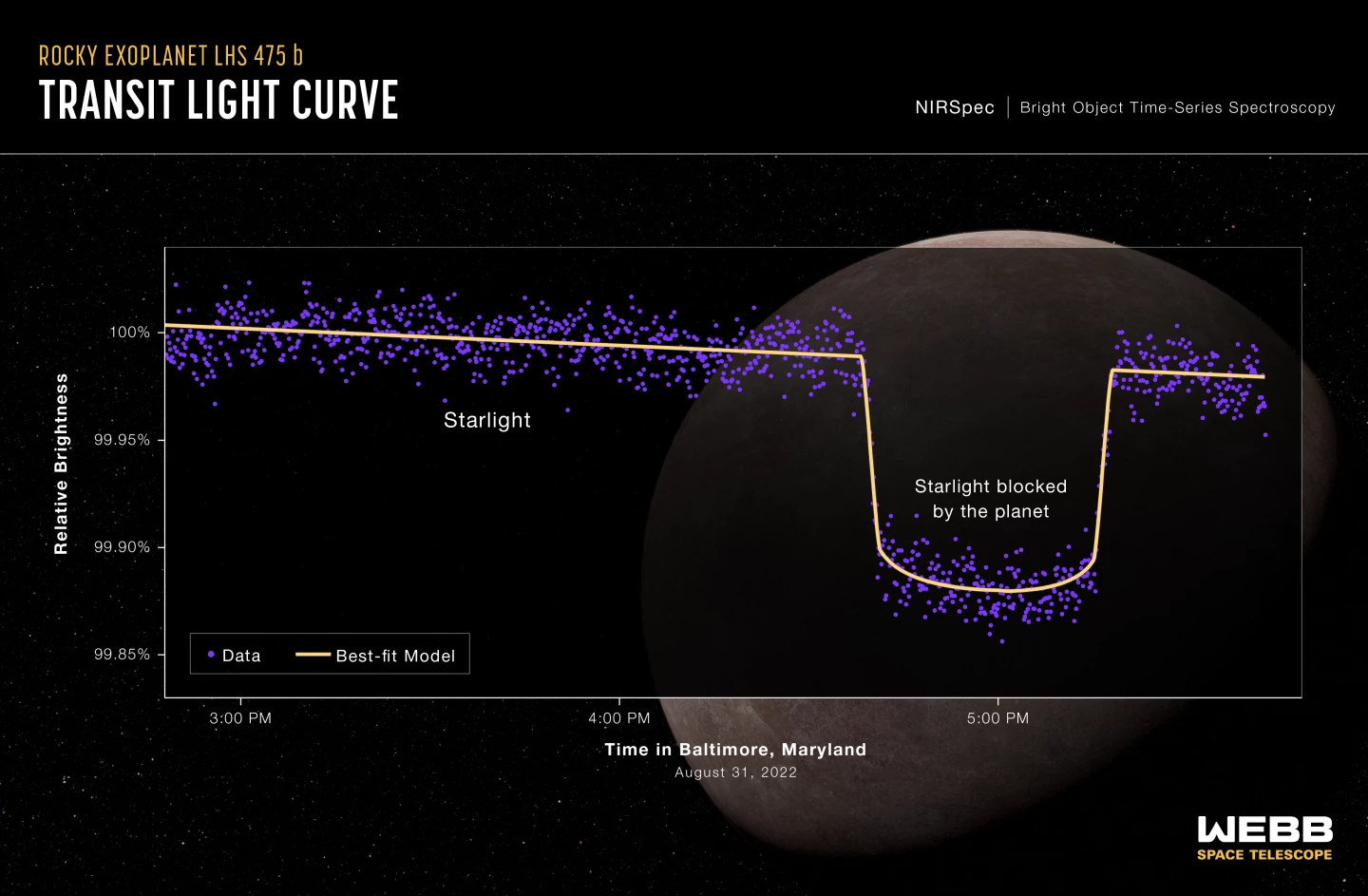

TESS and many other instruments detect exoplanets using what’s called the transit method. Essentially, if you watch a star for long enough, you might see dips in the brightness of its light, and if these happen on a predictable pattern, they can indicate that a planet is passing in front of the star.

TESS had seen an inkling of this around LHS 475 but couldn’t confirm the presence of a planet, so the team trained Webb on the system. And sure enough, after just two transits, the instrument was able to confirm the exoplanet, demonstrating its power.

The new world was dubbed LHS 475 b, and orbits a star just 41 light-years away in the constellation Octans. It completes an orbit once every two days, and appears to be 99% the diameter of Earth. While it’s tucked in very close to its host star, it may still orbit within the habitable zone, since the star is a dim, cool red dwarf.

Don’t be fooled into thinking this is a nice, pleasant Earth twin, though. LHS 475 b is much hotter, by a few hundred degrees, and may either have an atmosphere of pure carbon dioxide or no atmosphere at all.

To investigate further, the scientists are scheduled to examine the planet with Webb in more detail later this year, to study the composition of its atmosphere. This is a major step towards the telescope’s goal of seeking out signs of life on exoplanets.

“These first observational results from an Earth-size, rocky planet open the door to many future possibilities for studying rocky planet atmospheres with Webb,” said Mark Clampin, Astrophysics Division director of NASA. “Webb is bringing us closer and closer to a new understanding of Earth-like worlds outside our solar system, and the mission is only just getting started.”

The research was presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society on January 11.

Source: NASA