In one small step for humankind, scientists have seen a fertilized mouse egg develop naturally and normally into early embryonic form. While a long way to go, it’s a positive sign that mammalian – namely, human – reproduction can take place in space.

The research team, from the University of Yamanashi, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and government-funded research institute Riken, launched 720 frozen two-cell mouse embryos into space aboard aboard SpaceX CRS-23 on August 29, 2021.

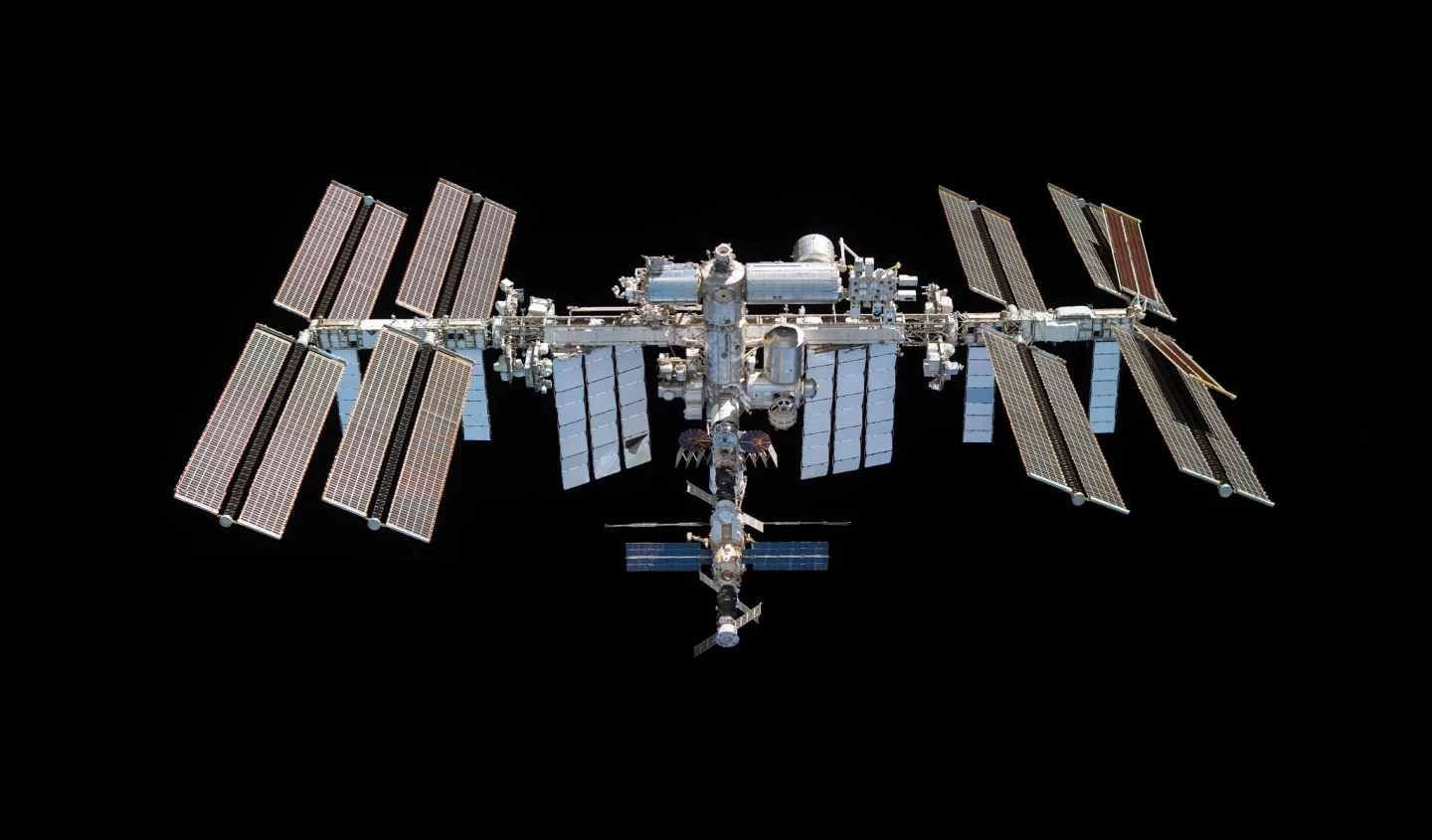

As part of the simply named project “Space Embryo”, the scientists also designed a device that allowed astronauts to easily handle the precious scientific cargo, which was thawed and cultured on the International Space Station (ISS). Astronaut Akihiko Hoshide, on a long-term ISS mission, handled the experimental stage in early September, preparing the embryos in several different gravitational conditions, before they were couriered back to Earth a few days later for testing.

In the laboratory, the Japanese team were pleased to see that the embryos had undergone the normal division of early embryonic development and had formed blastocysts with an inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE). As an embryo develops, the ICM will ultimately form the fetus, while the TE will form the placenta.

Because of the way the ICM clusters at one spot in the blastocyst cavity during this pivotal early stage of embryonic development, the scientists were concerned that an environment lacking gravity may have a harmful impact on these minute biological natural processes.

Most pleasingly, the embryos cultured under microgravity (also known as zero gravity) developed in a similarly ‘normal’ way to those cultured in artificial gravity settings.

“The embryos cultured under microgravity conditions developed [normally],” noted the team, led by University of Yamanashi professor Teruhiko Wakayama, in a statement.

While scientists have hatched newts and killifish in microgravity space before, there has been little work on mammalian reproduction due to many difficulties involved in breeding in this environment.

As well as the normal processes, the lab determined there were also no significant changes in the state of the DNA and genes within the blastocysts.

“In the future, it will be necessary to transplant the blastocysts that were cultured in ISS’ microgravity into mice to see if mice can give birth,” the team added.

The research was published in the journal iScience.

Source: University of Yamanshi, Riken, via phys.org