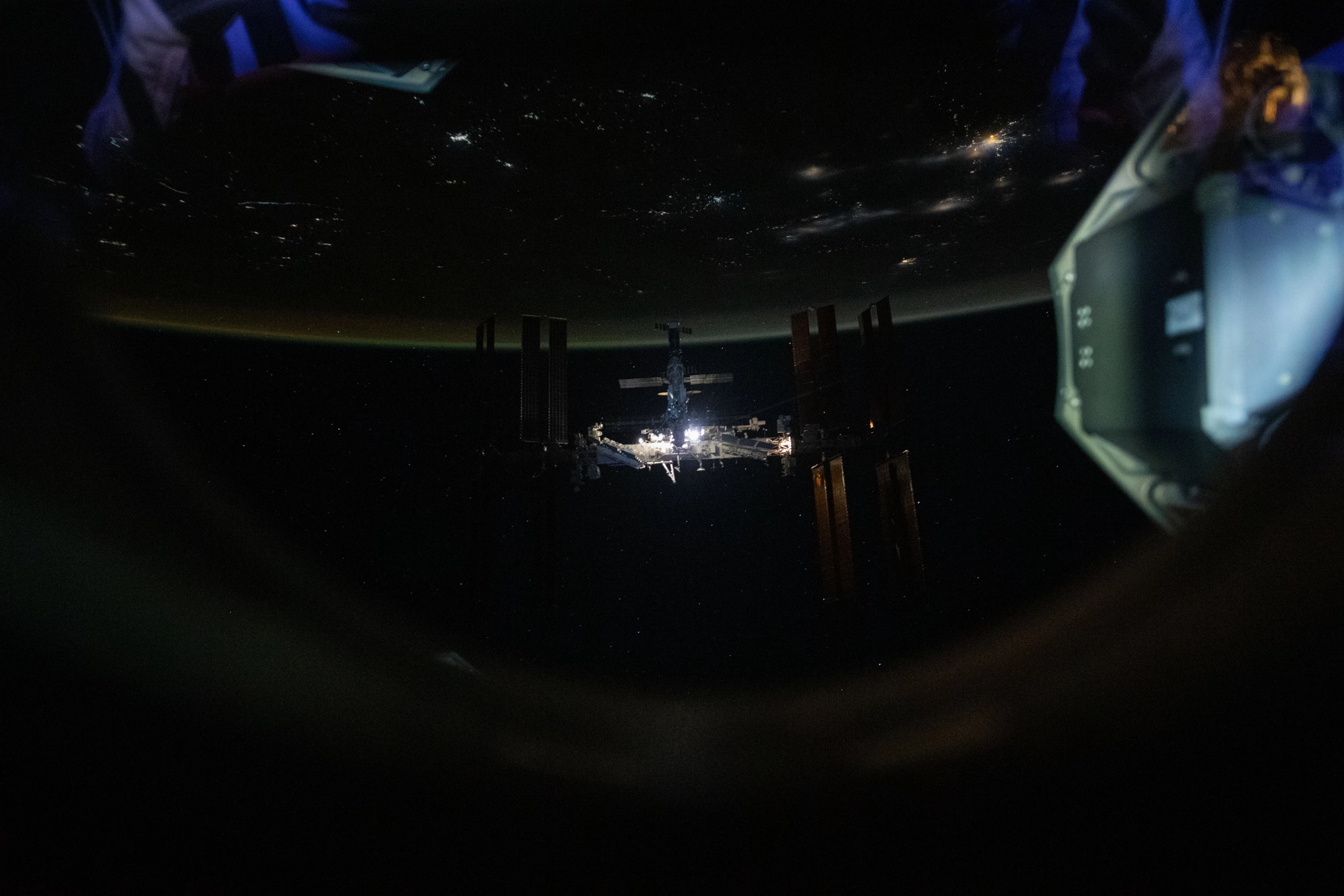

NASA has released its updated plans that outline the International Space Station's (ISS) final years leading up to its eventual disposal in 2030, when it will plunge into the Earth's atmosphere and burn up somewhere over the South Pacific Ocean.

Ever since it was first announced in the 1980s, the project that would eventually become the ISS has been plagued by controversy, radical changes to its mission, uncertainty as to how long the United States would remain involved in the station's running, and even how long the space lab would even exist.

The idea of an American space station began life in the mind of rocket pioneer Werner Von Braun, who saw it as a base from which crewed missions to Mars and beyond could be assembled and launched. In fact, the Space Shuttle was given the green light to ferry supplies needed for the station and the building of Mars ships.

That plan rapidly fell by the wayside when the Nixon administration postponed the Mars mission indefinitely, but, in the 1980s, the station was back on track. Officially, it was America's answer to the Soviet's Salyut space stations, though some cynics said that it was just somewhere for the Space Shuttle to go.

As time went on, Japan and ESA entered a partnership with NASA to supply modules for the station, and in 1993 Russia signed on for what was now the International Space Station – partly as a sign of solidarity between the US and post-communist Russia, but also as a way to keep Russian space engineers employed at home rather than selling their skills abroad.

Over its career, the question has remained as to the future of the ISS. Would it be abandoned in 2016? 2020? 2025? Would it make it to 2030, but without American participation for the last five years, or would Russia reclaim its modules to build its own station?

With the Biden administration committed to keeping the US involved in the ISS program through 2030, NASA has now outlined the last eight years of the station's life and how the lab will be disposed of.

Leaving aside a long list of experiments, initiatives, budget items, and general platitudes about helping all humanity, ISS operations until 2030 will involve a number of steps, some of which are already underway. New equipment, for example, is being installed in the station to keep it fully functioning, and engineering evaluations are ongoing to make sure that the ISS remains structurally sound, though NASA says that the thermal and gravitational stresses are taking their toll and the station will not remain safe beyond the end of the decade.

Another part of the plan is to move away from the ISS being a purely government-run station to being one involving more and more private businesses. As part of this, NASA is funding various projects to enhance private industry's knowledge, skills, and experience in working in low-Earth orbit so it can take responsibility for tasks other than running experiments or ferrying crews from American soil to the station.

The eventual goal is for companies to build their own space stations, beginning with private modules that will be installed on the ISS for testing and evaluation before undocking to form the core of new stations. By 2030, NASA will be sending its astronauts to these stations or hiring private astronauts to carry out services for the space agency.

Without saying it in so many words, America's vision is for low-Earth orbit to be the domain of private companies who will work for NASA as well as other customers as the agency focuses its human spaceflight program on the Moon and Mars, with perhaps a national space laboratory in Earth orbit.

As to the ISS, the plan is to carry on with normal operations, though from 2026 on the lab will be allowed to gradually lose altitude. From June to November 2030, three additional uncrewed Progress cargo ships will dock with the station and use their engines to slow down the ISS. The exact timetable will depend on solar activity, which can expand the Earth's atmosphere and increase drag.

When the station reaches an altitude of 280 km (174 miles), it will pass the point of no return and it will not be possible to return it to a safe orbit. After the final engine burns, it will plunge into the Earth's atmosphere in a controlled reentry that will see it break up over the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area (SPOUA), where any unconsumed parts of the station will fall into the sea.

"The private sector is technically and financially capable of developing and operating commercial low-Earth orbit destinations, with NASA’s assistance," said Phil McAlister, director of commercial space at NASA. "We look forward to sharing our lessons learned and operations experience with the private sector to help them develop safe, reliable, and cost-effective destinations in space. The report we have delivered to Congress describes, in detail, our comprehensive plan for ensuring a smooth transition to commercial destinations after retirement of the International Space Station in 2030."

The announcement of the official extension of the ISS mission through 2030 can be seen in the video below.

Source: NASA (PDF)