The most abundant metal known to man is iron. It's everywhere. Not just on Earth, but in space as well. Astro engineers have just figured out how to use iron – or nearly any metal for that matter – as plasma rocket fuel.

We already know that some metals can be violently flammable. Lithium reacts with water and burns quite intensely. Magnesium and titanium are common in fireworks for their intense flames and sparks. Aluminum, which makes up about 8% of the metals found in the Earth's crust is already used in solid rocket propellants.

But iron? While iron oxide is a key ingredient to thermite, it's not something one generally thinks of as a fuel source.

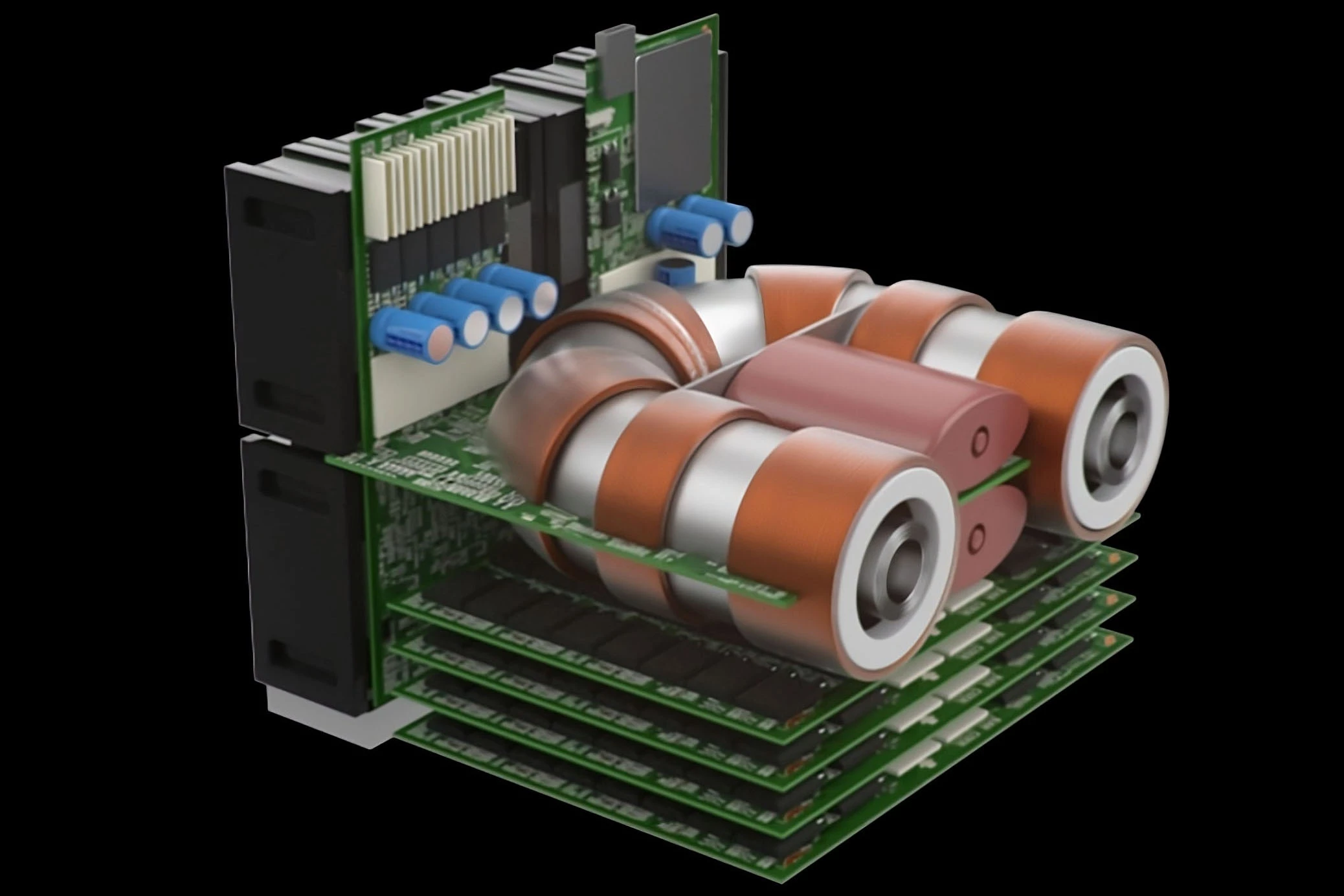

Astronautical engineers at Magdrive have developed a unique plasma thruster for use in space that's capable of using nearly any metal type as the fuel source, which means spacecraft would not have to return to Earth for refueling. Instead, comets, asteroids, moons or anything else floating in the vast expanses of space can simply be harvested for their metal contents to be used as fuel.

They call it the Super Magdrive.

The process starts with solar panels that collect and store energy in capacitors. The stored energy is then discharged at a very high rate – over 1,000 volts – to ionize the metal. This process creates a high-density and high-temperature train of plasma "bullets" in a confined area that can be accelerated and "shot out" directionally using magnetic fields to produce thrust.

Conventional chemical rockets would still be required to get the vehicle into space. Plasma rockets simply do not have enough thrust to get off the ground, let alone leave Earth's atmosphere. Once in the vacuum of space, however, plasma thrusters would have no issue in propelling and steering craft.

The Super Magdrive is said to generate thrust "an order of magnitude higher than similarly sized electric propulsion systems." In scientific terms, that generally means a factor of ten times more. That being said, Howe Industries is developing a Pulsed Plasma Rocket engine design to have 100,000 N (73,756 lbf) of thrust and specific impulse of 5,000. We haven't seen thrust figures for the Super Magdrive yet.

Scientists from the University of Southampton have been working with UK-based Magdrive on validating the plasma propulsion system thrust capabilities.

"Spacecraft have limited amounts of fuel because of the enormous cost and energy it takes to launch them into space," said lead scientist Dr. Minkwan Kim, of the University of Southampton. "But these new thrusters are capable of being powered by any metal that can burn, such as iron, aluminum or copper. Once fitted, spacecraft could land on a comet or moon, rich in these minerals, and harvest what it needs before jetting off with a full tank."

For now, Magdrive is focused on satellites. Using the Super Magdrive technology, it believes fuel costs can be significantly reduced as well as lighter payloads to keep satellites safe in their intended orbital operations by providing thrusters that use easily attainable and abundant fuel: metal.

Dr. Kim added "The system could help us explore new planets, seek out new life, and go where no human has gone before – enabling never-ending discovery."

In January of 2023, "Operation Get it Up" saw the launch of the first Super Magdrive aboard the SpaceX Falcon 9 Transporter-6 mission. Initial reports confirmed successful deployment, however, no further updates on performance have been provided. We do know that Magdrive intends on launching a plasma thruster five times more powerful than the last for testing in June of 2025 dubbed operation "So Much for Subtlety."

Source: University of Southampton