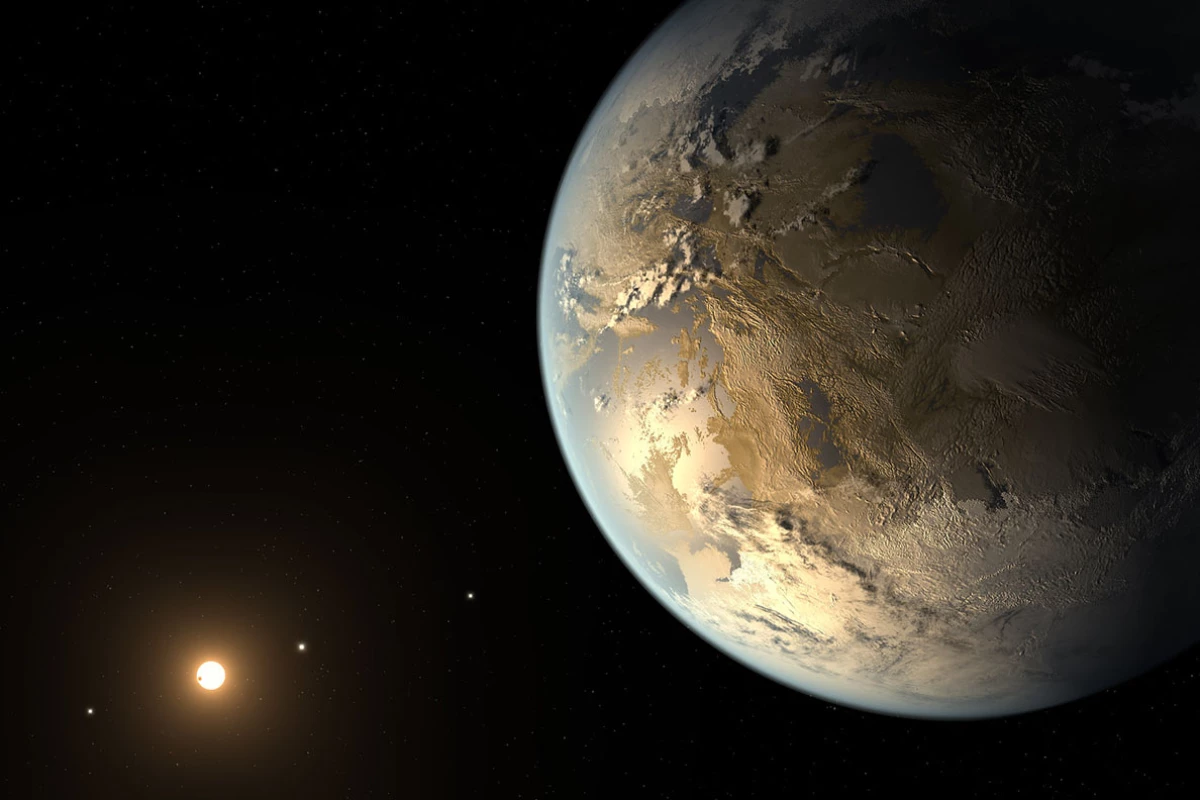

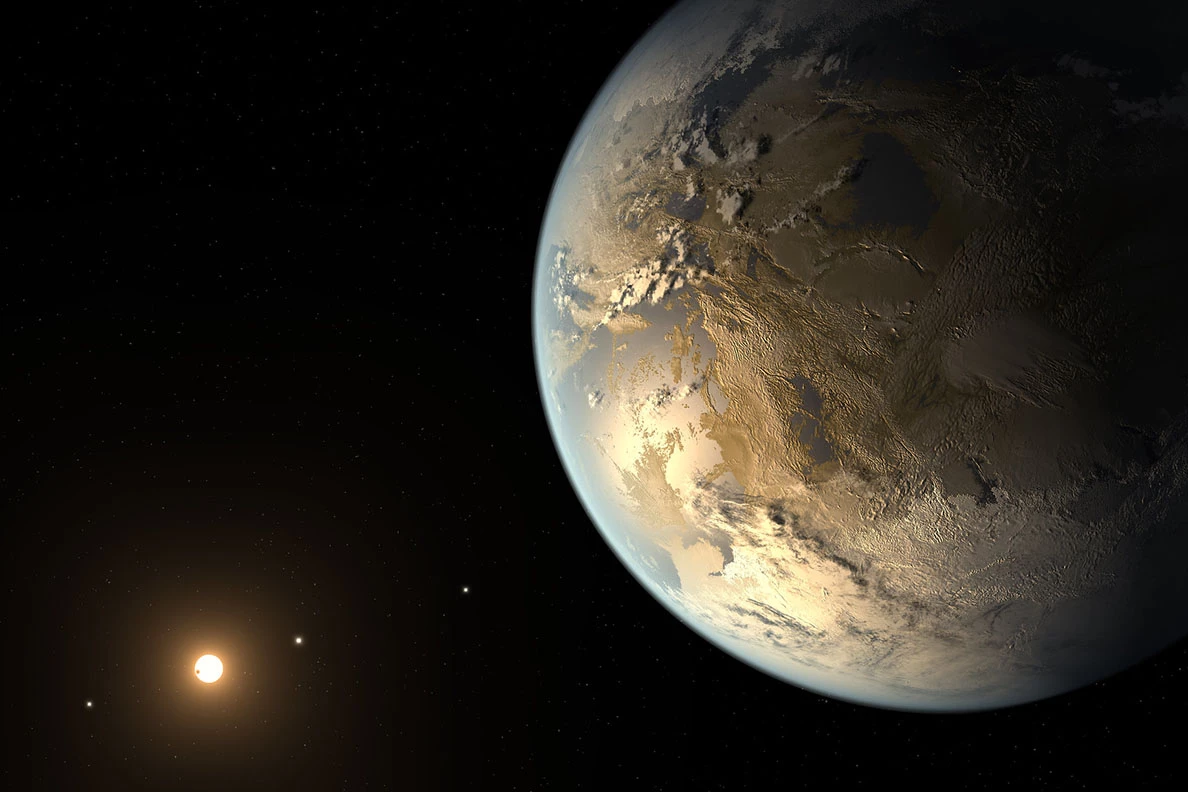

A team of scientists led by Washington State University (WSU) geobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch has identified two dozen exoplanets that could be more favorable to life than the Earth. Based on data from the Kepler mission, these super-habitable worlds may have conditions more suitable for sustaining life for a longer period of time than our planet.

One of the major questions vexing modern science is whether there is life elsewhere in the universe. While no direct evidence of such life has been discovered, exoplanet-hunting missions like Kepler have changed many of our ideas about how planetary systems are formed and have provided scientists with the means to think about life beyond our solar system without leaning so heavily on conjecture and speculation.

Out of the more than 4,000 exoplanets found so far, a number have been deemed to be habitable, though this is a somewhat misleading term. It doesn't mean a planet where one could land and start homesteading. It means a rocky planet that is in the right orbital region around its star where the temperature is moderate enough for liquid water to exist on its surface without freezing or boiling away. To give an idea of how generous this is, Earth is habitable under these criteria, but so are Venus and Mars, which are scarcely garden spots.

Now, WSU has refined the search a bit and have come up with 24 candidate exoplanets that are not only habitable, but potentially more habitable than the Earth. Situated more than 100 light years from the Sun, these exoplanets culled from the Kepler Object of Interest Exoplanet Archive of transiting exoplanets were selected because they have some properties that might make them better able to sustain life.

One thing that the researchers suggest could make a planet more habitable would be its sun. The usual assumption is that an orbit around a G-type star like the Sun would be the best place to find a habitable planet. However, such stars only have a lifespan of about eight to 10 billion years, and it took four billion for anything other than the simplest of life to evolve on the Earth. A K-type dwarf star, on the other hand, would be cooler and less massive than the Sun, but it would have a lifespan of up to 70 billion years – allowing for a much longer time for life to emerge and develop.

Another pair of factors would be size and mass. Part of the reason the Earth is habitable is because it's large enough to be geologically active, giving it a protective magnetic field, and has enough gravity to retain an atmosphere. According to the team, if a planet was 10 percent larger, it would have more surface area to live on. If it was 1.5 times as massive as the Earth, its interior would retain more heat from radioactive decay, would remain active longer, and hold onto its atmosphere for a longer time.

In addition, if a world was 5° C (8° F) warmer than the Earth and had more water, it would enjoy the biodiversity of a rainforest over much of the planet.

The team says that none of the 24 planets found have all of these characteristics, but one has four of the critical factors. At any rate, all 24 could be the focus for later telescopic studies.

"It’s sometimes difficult to convey this principle of super-habitable planets because we think we have the best planet," says Schulze-Makuch. "We have a great number of complex and diverse lifeforms, and many that can survive in extreme environments. It is good to have adaptable life, but that doesn’t mean that we have the best of everything."

The research was published in Astrobiology.

Source: Washington State University