Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin have created a mind-reading AI system that can take images of a person’s brain activity and translate them into a continuous stream of text. Called a semantic decoder, the system may help people who are conscious but unable to speak, such as those who’ve suffered a stroke.

This new brain-computer interface differs from other ‘mind-reading’ technology because it doesn’t need to be implanted into the brain. The researchers at UT Austin took non-invasive recordings of the brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to reconstruct perceived or imagined stimuli using continuous, natural language.

While fMRI produces excellent quality images, the signal it measures, which depends on blood oxygen levels, is very slow, as an impulse of neural activity causes a rise and fall in blood oxygen over about 10 seconds. Because naturally spoken English uses more than two words per second, each brain image can therefore be affected by more than 20 words.

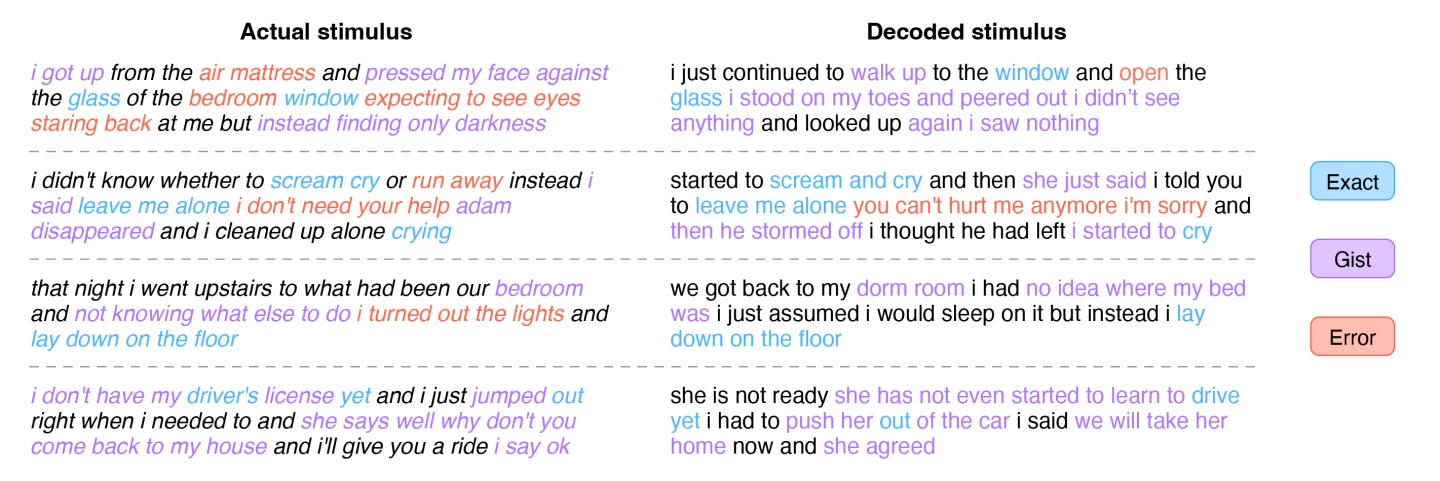

That’s where the semantic decoder comes in. It uses an encoding model similar to that used by Open AI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard that can predict how a person’s brain will respond to natural language. To ‘train’ the decoder, the researchers recorded three people’s brain responses while they listened to 16 hours of spoken stories. The decoder could predict, with considerable accuracy, how the person’s brain would respond to hearing a sequence of words.

“For a noninvasive method, this is a real leap forward compared to what’s been done before, which is typically single words or short sentences,” said Alexander Huth, corresponding author of the study.

The result does not recreate the stimulus word for word. Rather, the decoder picks up on the gist of what’s being said. It’s not perfect, but about half the time, it produced text that was closely – sometimes precisely – matched to the original.

When participants were actively listening to a story and ignoring another story being played simultaneously, the decoder was able to capture the gist of the story being actively listened to.

As well as having participants listen to and think about stories, they were asked to watch four short, silent videos while their brains were scanned using fMRI. The semantic encoder translated their brain activity into accurate descriptions of certain events from the videos they watched.

The researchers found that willing participation was key to the process. Those who put up resistance during the encoder training, such as deliberately thinking other thoughts, produced unusable results. Similarly, when the researchers tested the AI on people who hadn’t trained the decoder, the results were unintelligible.

The UT Austin team is aware of the potential for malicious misuse of inaccurate results and the importance of protecting people’s mental privacy.

“We take very seriously the concerns that it could be used for bad purposes and have worked to avoid that,” said Jerry Tang, lead author of the study. “We want to make sure people only use these types of technologies when they want to and that it helps them.”

Currently, the decoder is not usable outside of the lab environment because of its reliance on fMRI. The hope is that the technology can be adapted for use with more portable brain imaging systems such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

“fNIRS measures where there’s more or less blood flow in the brain at different points in time, which, it turns out, is exactly the same kind of signal that fMRI is measuring,” Huth said. “So, our exact kind of approach should translate to fNIRS.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, and the video below shows how the semantic decoder uses recordings of brain activity to capture the gist of a silent movie scene.

Source: University of Texas at Austin