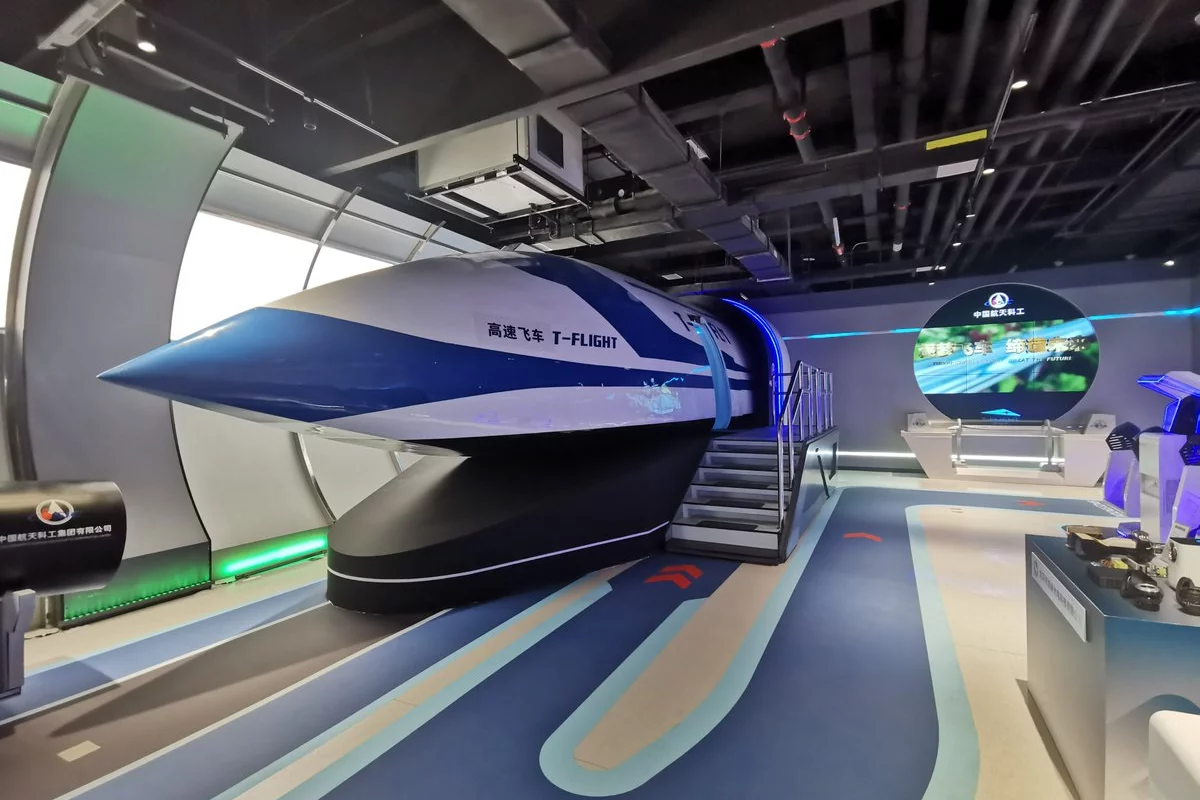

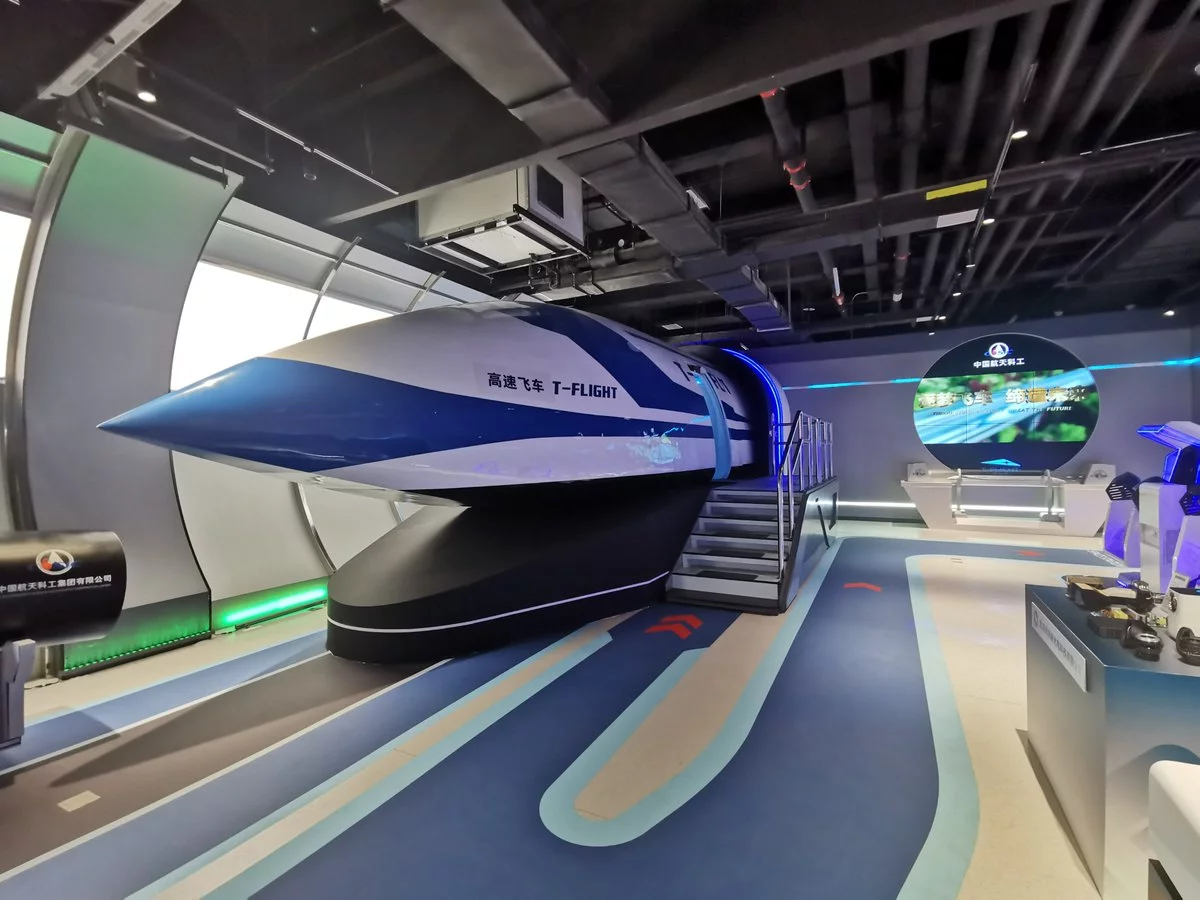

In February of this year, we reported on the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, and its phase one testing of a low-vacuum-tube hyperloop-style maglev ultra-high-speed (UHS) train. In initial 1.24-mile-long (2-km) tests, the T-Flight hit a whopping 387 mph (623 km/h).

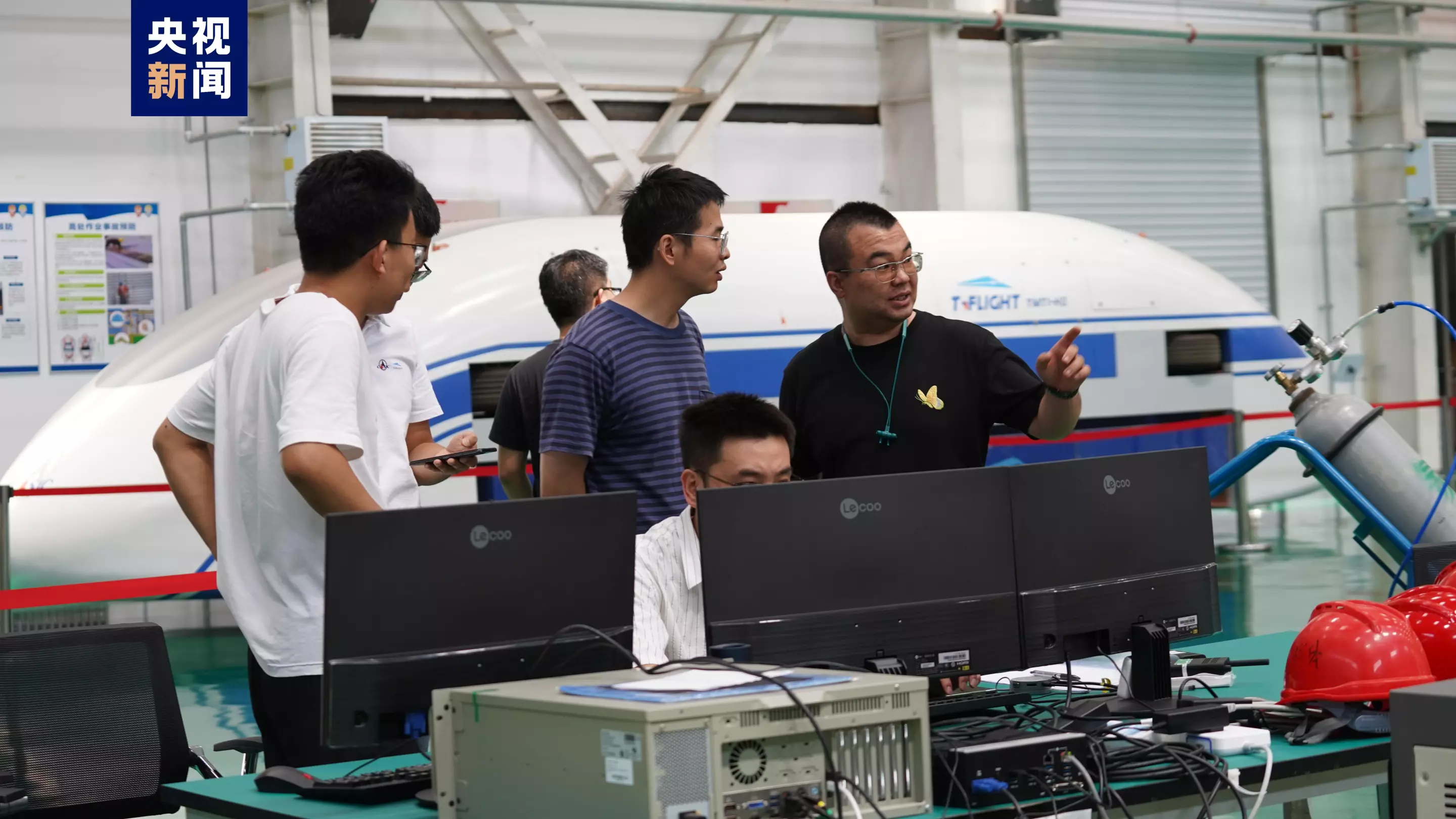

On its last go-around in October of 2023, it ran the fairly short track under non-vacuum conditions. This week, CASIC – unironically known for being China's largest maker of strategic and tactical missiles – has just successfully tested the UHS maglev under low-vacuum conditions on that very same track with successful results. According to CGTN, "the test showed that the maximum speed and suspension height of the vehicle were consistent with the preset values."

The test showed that all systems were nominal, and the train's speed and height above the track lined up with the preset values of the test – which were not disclosed. CASIC was able to verify that all large-scale vacuum-related systems were also in working order during the test. All systems, check!

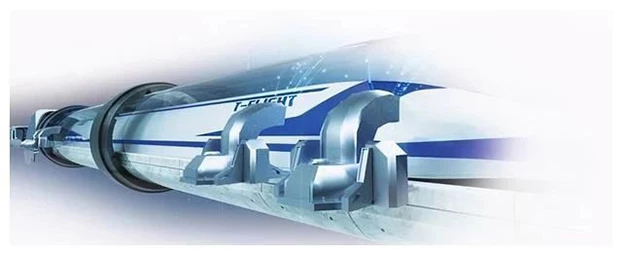

The idea of high-speed vacuum-tube transport has largely petered out in the West, but it's still an intoxicating idea. With little-to-no atmosphere, aerodynamics and wind resistance become almost completely a non-factor. Not to mention friction, drag and heat, as the train effectively floats in the air, touching nothing at all, powered and levitated by magnetic repulsion.

Frictionless maglev trains have of course been around for some time now. Japan's L0 Series Maglev, built in 2012, holds the record for being the fastest train in the world, clocking in at a speedy 374 mph (602 km/h). And China already has the second fastest, built a few years ago in 2021, currently clocked at only 1 mph (1.6 km/h) slower than the Japanese train.

The T-Flight has the advantage of being in a low-vacuum tube, where outside atmospheric forces will have little effect on the train's speed or stability, depending on the amount of vacuum. Normal atmospheric pressure at sea level is 14.7 psi (1 bar), whereas "low-vacuum" could be from 1 psi (0.07 bar) to around 13.7 psi (0.9 bar). We don't have the exact figures used in their test, but an educated guess would say it's closer to the lower end of the scale.

The goal of the T-Flight maglev train system is to connect megacities via an ultra-high-speed railway capable of getting passengers from cities such as Beijing to Shanghai in as little as an hour and a half. For reference, that's a 680-mile (1,100-km) journey that takes 4.5-6.5 hours on existing high-speed rail. Even flights take a little over two hours, plus commutes at either end. The fastest traditional trains take 12 or more hours.

CASIC plans to run the T-Flight at its full 621-mph (1,000-km/h) top speed in the second phase of testing, which will require an extended track some 37 miles (60 km) long. That's about 100 mph (161 km/h) faster than the typical cruise speed of the most common airliner in the world; the Airbus A320.

According to a CASIC video from six years ago, there could also be a phase three, targeting 2,485 mph (4,000 km/h). That's not a typo. Mind you, six years ago, the group also said phase two would target 1,242 mph (2,000 km/h), which seems to have been walked back.

Even so, the T-Flight has already gone faster than the world's fastest maglev train, on a comically short track, and without the aid of a low-vacuum environment. In a low-vacuum environment, with some room to stretch its legs, it'll undoubtedly go much faster.

China certainly has the population to make advanced mass transit projects economically viable – but it remains to be seen whether the country has the will and wherewithal to push the insane expense of a super-long-range vacuum tube through to completion. Every capitalist attempt thus far has failed.

And the safety questions remain; what happens if the tube depressurizes and throws unexpected variables into the aerodynamic equations? Can you really fire passengers through a low-vacuum tube at these speeds and expect them all to remain in a solid state? Is this all just a front for a giant railgun project that'll rain carriage-sized supersonic projectiles down on hapless enemies, as my colleague has mused, or will China persevere and deliver the hyperloop that Elon promised?

We're not sure how much CASIC has spent on the development of T-Flight thus far, or how much it will cost to complete, but with nearly a billion and a half inhabitants in China potentially ready to ride, and a Chinese state-owned company with annual revenues over US$30 billion in charge of making it happen, this very well could be a project rifled through to completion.

Source: Xinhua