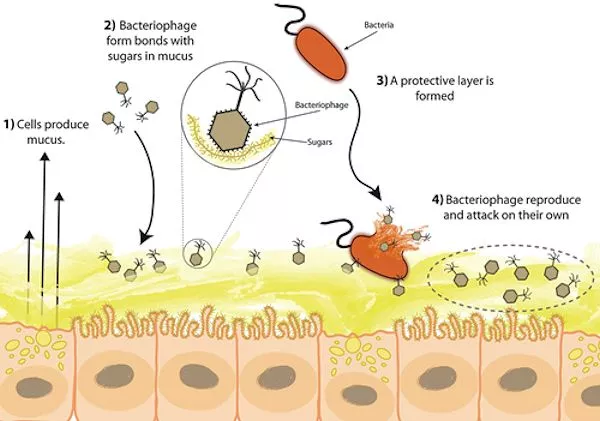

Though not something people like to ponder, the purpose of mucus as a protective barrier that keeps underlying tissues moist and traps bacteria and other foreign organisms is well known. However, researchers at San Diego State University (SDSU) have now discovered that the surface of mucus is also the site of an independent human immune system that actively protects us from infectious agents in the environment.

Mucus is produced by tissue that lines the inner surfaces of the body which come into contact with the outer environment. The mouth, nose, sinuses, throat, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract all possess mucus-producing tissue. The mucus layer has long been identified as providing protection against the outside world, but in a rather passive manner.

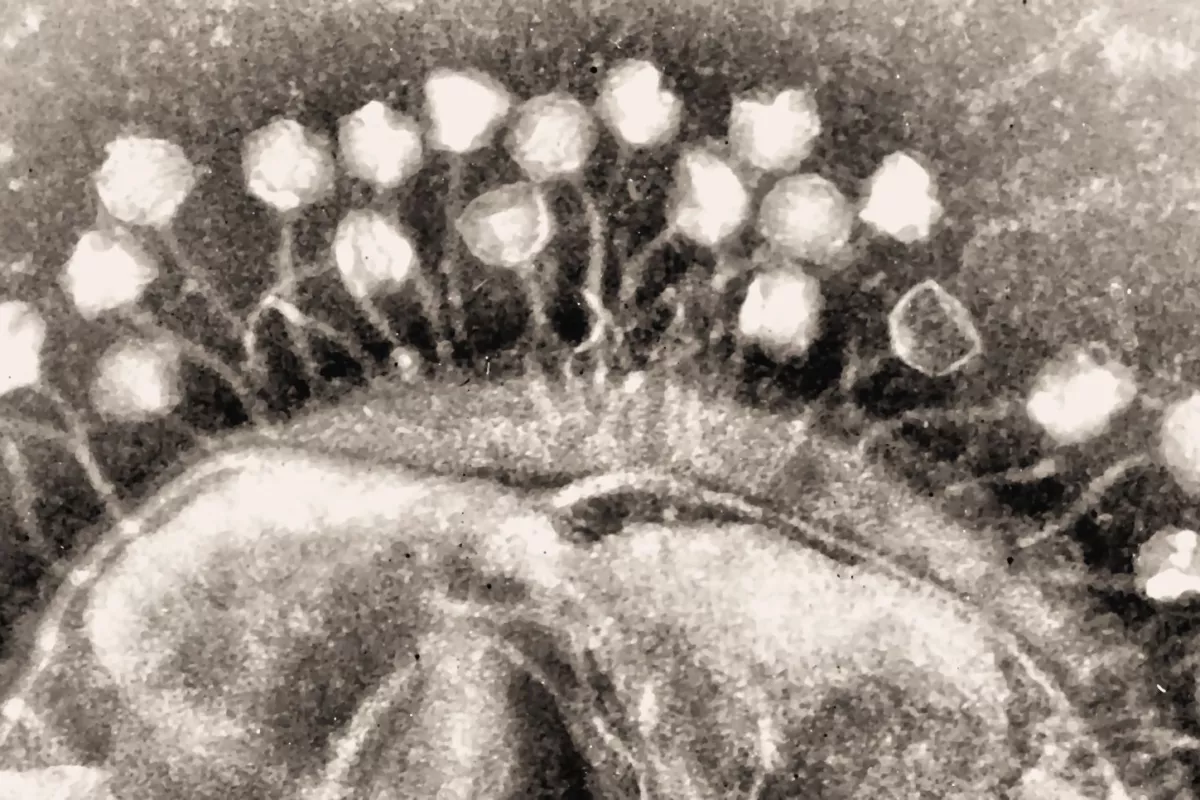

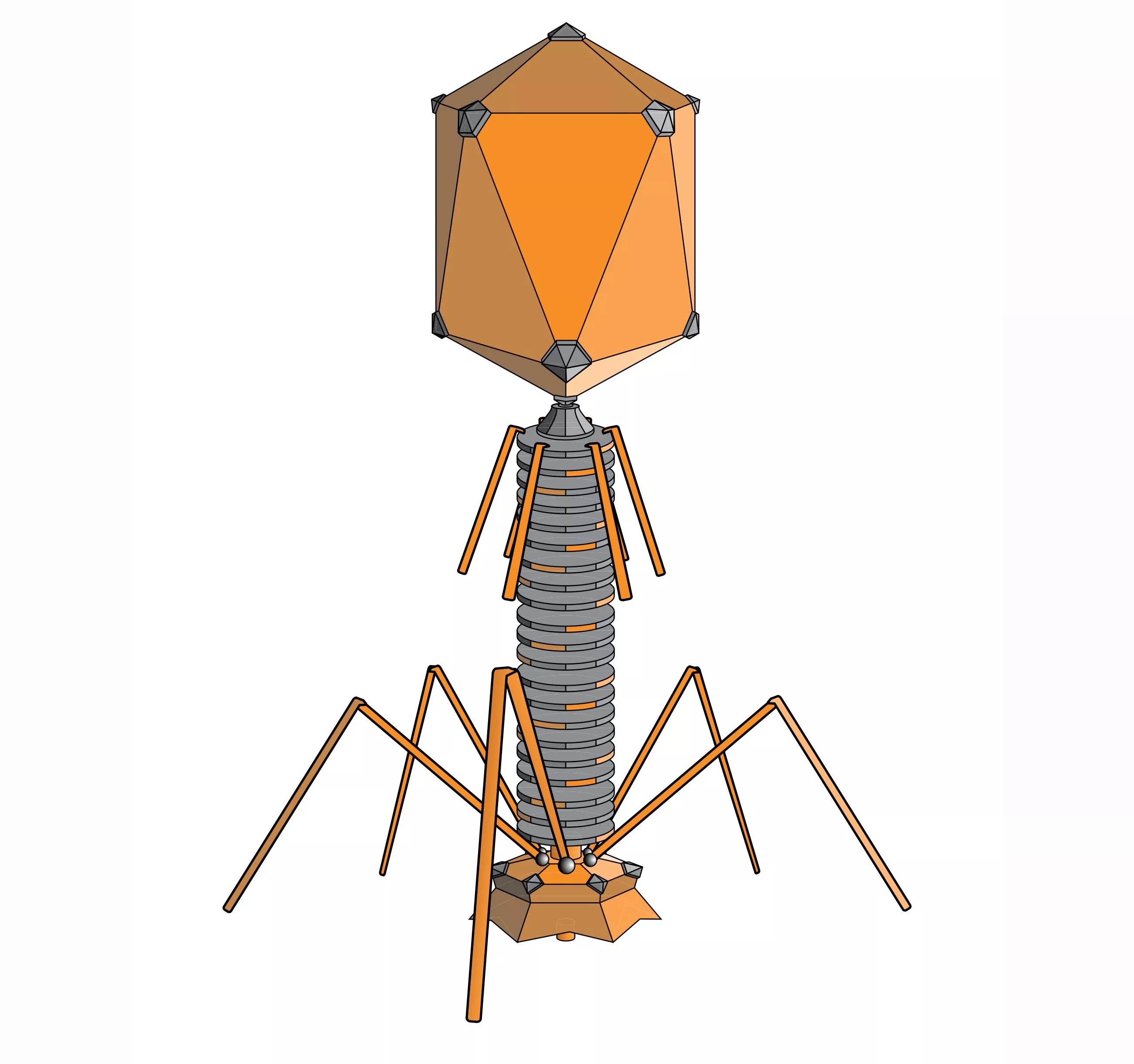

No longer. An SDSU research team led by biology post-doc Jeremy Barr has discovered that a previously unsuspected immune system is active on the surface of the mucus layer. This immune system consists of a layer of bacteria-infecting viruses (bacteriophage), that actively attack and kill infectious (and harmless) bacteria as the viruses multiply.

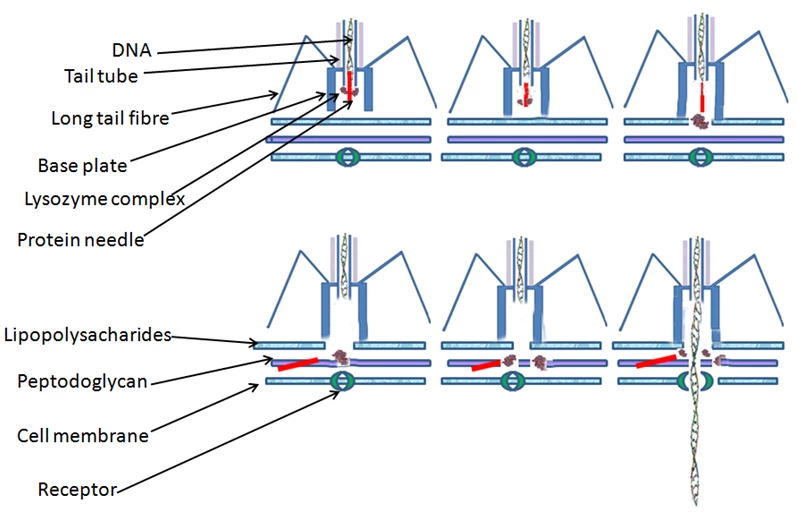

When bacteriophage comes in contact with the surface of a layer of mucus, they bond to sugar molecules, which causes the viruses to adhere to the mucus surface. When such a layer was exposed to E. coli bacteria, the SDSU researchers found that the bacteriophage immediately attacked and killed the E. coli. The bacteriophage layer acts as a powerful anti-microbial barrier that protects animals from infection and disease.

To double check this hypothesis, cells not coated by mucus were also exposed to E. coli. The cell death rate was three times greater for the non-mucus coated cells than for those coated with mucus.

Many varieties of bacteriophage are collected on the mucus layer of animals from the environment. These take on a role to defend the animal from infection by killing infectious intruders. The bacteriophage find the mucus layer to be a pleasant environment, where they find comfortable living conditions and plenty of food and hosts for replication of the bacteriophage: a win-win situation for all.

“This discovery not only proposes a new immune system but also demonstrates the first symbiotic relationship between phage and animals,” Barr said. “It will have a significant impact across numerous fields.”

Source: San Diego State University