There are all kinds of critical infrastructure lying beneath the surface of our oceans – road and rail tunnels connecting land masses, pipelines for oil and gas, power cables connecting islands and countries, underwater research stations, and submerged dams and hydroelectric installations.

This is all painstakingly built and maintained. Engineers contend with the harsh environmental conditions in the water, figure out access to project locations, and deal with the limitations of materials that have to withstand corrosion and pressure underwater.

The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) wants to know if there's an easier way to go about maritime construction – could we simply 3D print such projects beneath the waves?

So in 2024, it issued a challenge to develop a three-dimensional concrete printing (3DCP) method and material variant that could work underwater. Oh, and the material had to incorporate seafloor sediment, so as to reduce the need to transport large quantities of it to the offshore location each time something needed to be built.

Researchers from the David A. Duffield College of Engineering at Cornell University stepped up to compete against five other teams in cracking this puzzle. Led by civil and environmental engineering professor Sriramya Nair and joined by interdisciplinary collaborators, the Cornell team branched its work 3D printing large-scale concrete structures using a 6,000-lb (2,722-kg) robotic system, and developed a novel two-stage 3DCP method.

The two-stage system overcomes a major difficulty in underwater construction: preventing the weakening of the material when the deposited cement particles fail to bind together tightly. This is usually addressed with what are called admixture chemicals – but those greatly increase the mixture's viscosity, to the point that the 3D printer can't pump it out.

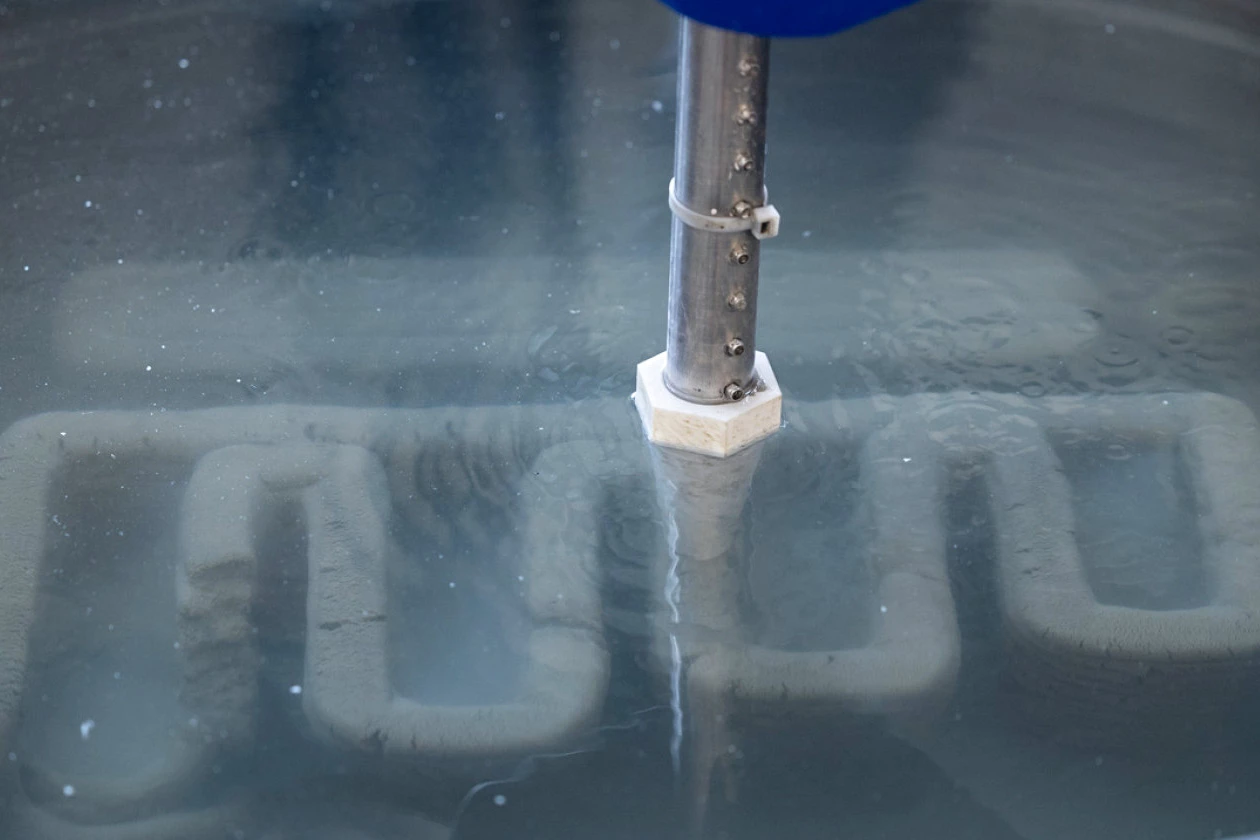

The team's solution involves injecting an admixture at the nozzle; this allows for the concrete material to be pumped smoothly and to rapidly solidify upon deposition. Since it's added in this two-stage process instead of being mixed into the base mixture, it allows compensation for temperature fluctuations and variations in printing speed and layer deposition rates. The team noted in a paper that appeared in Cement and Concrete Composites last November that this ensured precise and efficient construction.

"It turned out, with our mixture we could actually 3D-print underwater by making adjustments to account for continuous water exposure," said project lead Nair.

The team received a US$1.4-million grant last May for its research. It's since demonstrated numerous test prints in a large tub of water in a Cornell lab, where it can assess the strength, shape and texture of each arch of concrete being deposited.

To replicate this sort of monitoring offshore and underwater – where fine seafloor sediments can make the water cloudy and hard to see through when disturbed – the researchers built in a control box mounted on the robot arm with sensors that check for print quality, i.e. how the layers are deposited. This allows them to make adjustments to the printing setup in real-time.

The competing teams in the 3DCP challenge will face off next month as they 3D print an arch underwater and see which one turns out the best. The Cornell team is racing against the clock to bring together all its innovations in a bid to take home the prize. We'll keep an eye out for the results in March – stay tuned for updates.

Source: Cornell University