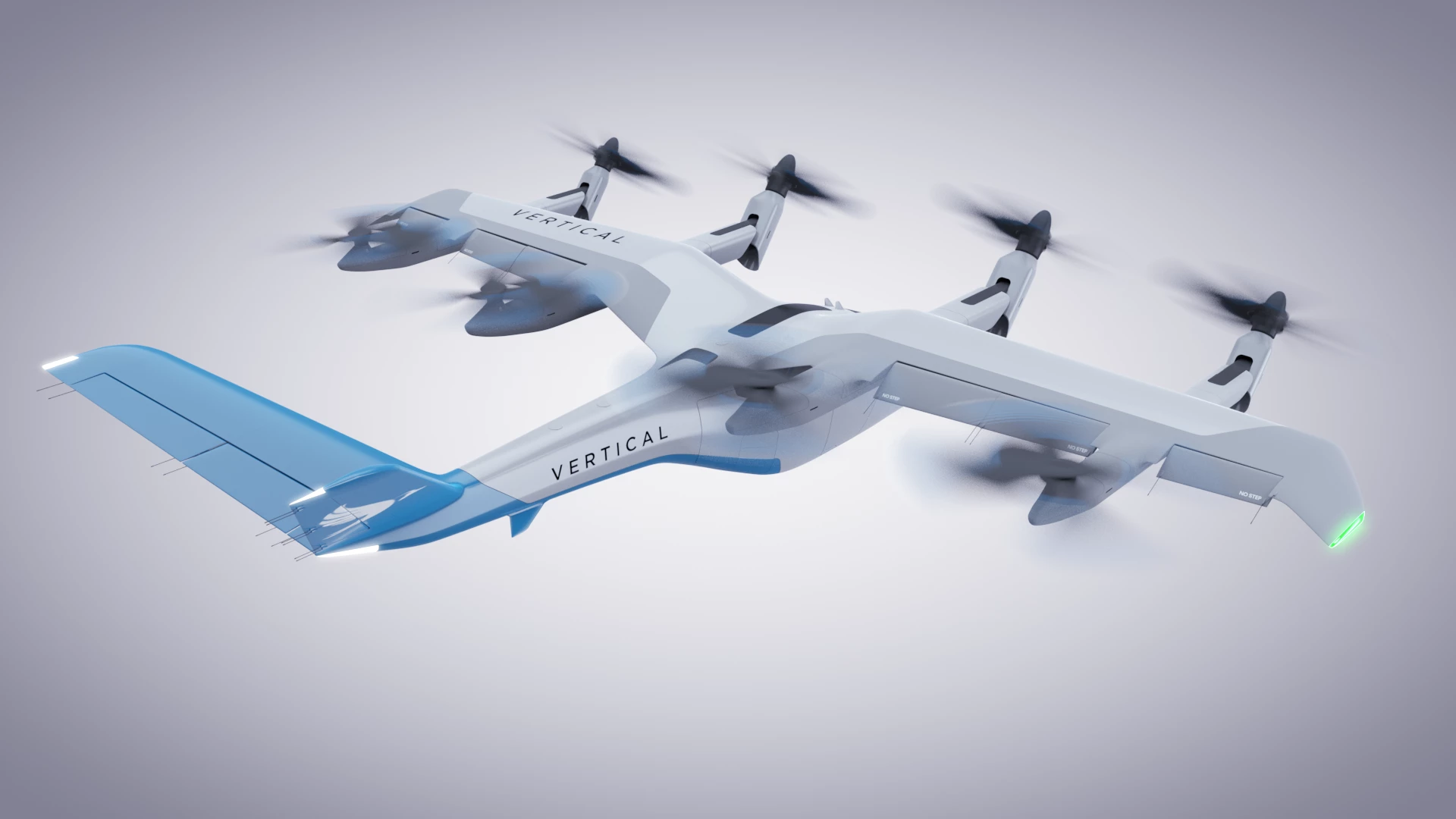

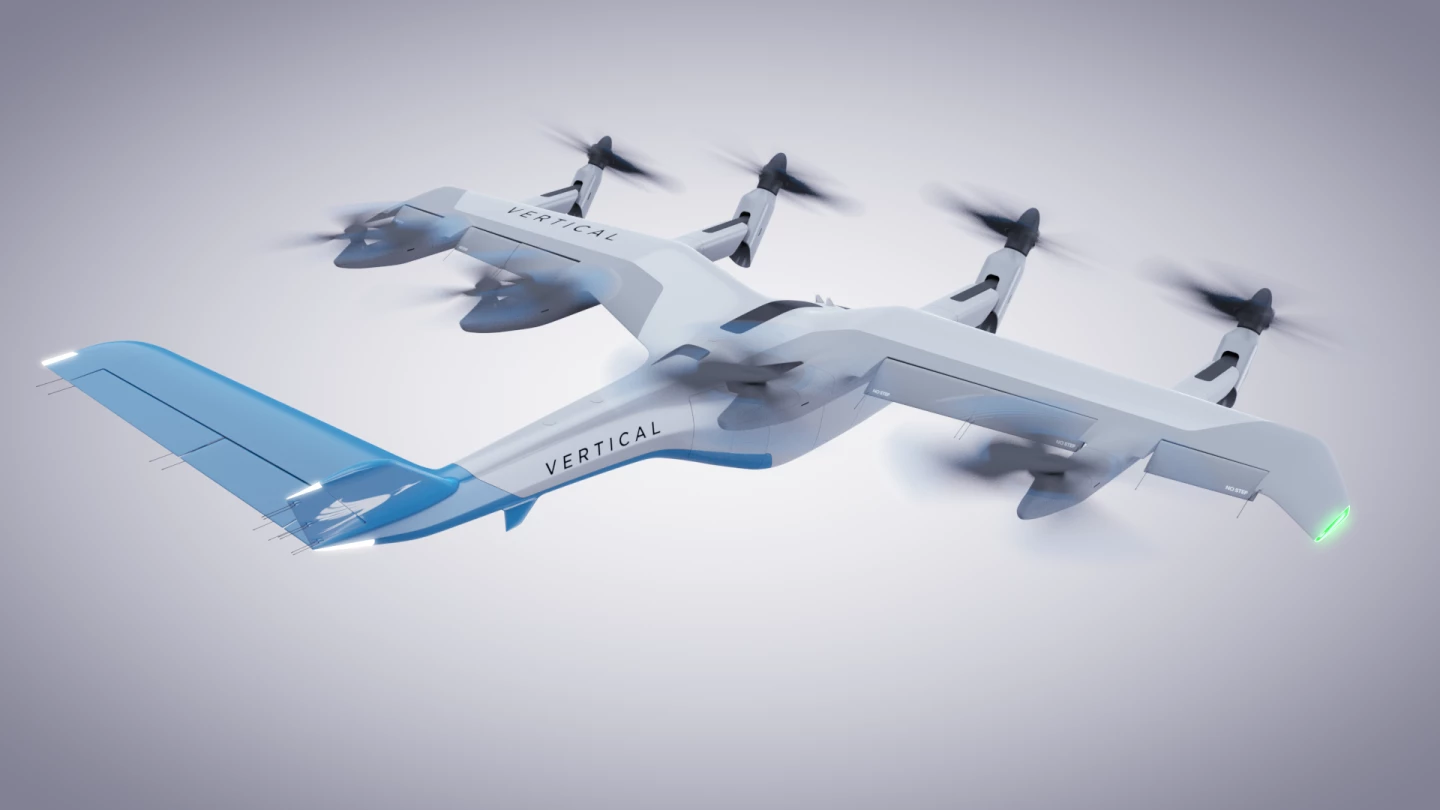

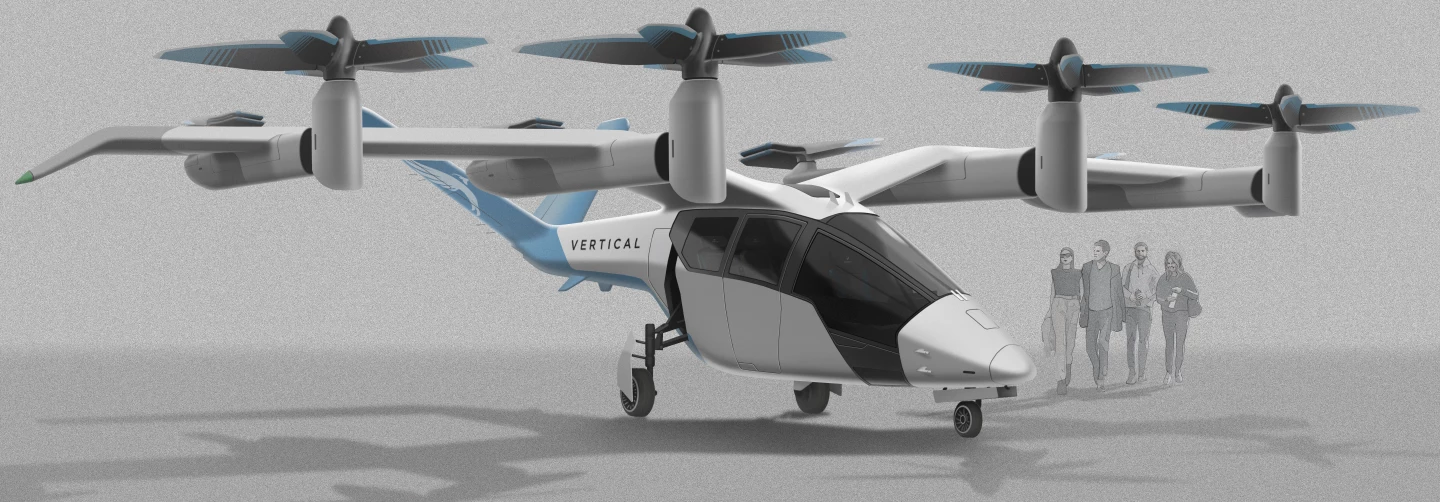

Last week, British company Vertical Aerospace unveiled a new electric VTOL air taxi design, moving out of the realms of simple multicopters and into the efficient, complex, longer-range world of tilt-rotor aircraft.

The VA-1X uses four tilting rotors on the leading edge of a long wing, with another bank of four rotors behind that stay in a vertical takeoff orientation, but separate and dovetail together to reduce drag once the aircraft gains enough horizontal airspeed to fly efficiently on the wing. The team expects a top cruise speed of around 150 mph (241 km/h), and a range of up to 100 miles (161 km) between charges from its lithium-based battery pack. It's designed to take off and land on a standard sized helipad, but much more quietly.

The company says the VA-1X is "set to be the world first certified winged all-electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) aircraft," which made us wonder, among other things, how Vertical Aerospace feels it will beat other companies like Lilium and Joby to the punch despite the fact that they're already well into testing of their transitioning eVTOL aircraft designs.

So we arranged a chat with Vertical Aerospace Chief Engineer Tim Williams, who joined the company a few months ago after some ten years as a Chief Engineer at Rolls-Royce, where he was accountable for a wide range of combat, transport and helicopter engines. What follows is an edited transcript.

Loz: Congratulations on your new concept, very nice looking aircraft you've got there!

Tim Williams: Thanks, yeah it is! We've put a lot of work into it, and there's still a long way to go, but it's shaping up to be really good.

How long's it been on the drawing board for?

We've been working through a number of different concepts since October/November last year. We've tried a few and discarded a few, and taken something that looked promising, and iterated a bit more, and finally we ended up with what we've got now. Quite a lot of consideration has gone into it

When you say you went through some other ideas and discarded them, is that something you're willing to talk about? There are so many different solutions popping up in this field.

There are, yeah. In terms of our previous aircraft, we started some three years ago with an aircraft called the POC, which was a four-rotor ducted quadcopter. We never intended that to be our final solution, just one of the building blocks on our journey.

Then we did an aircraft we called Seraph about a year ago, which was a 12-bladed multicopter. Again, that was to understand redundancy in the system, and how the aircraft behaves, and how a flight control system would behave, and again, that was just a building block.

We always realized that we wanted something with a really useful range, a hundred miles or so, and a fairly decent speed. So we've looked at lift and cruise-type configurations where you have fixed lift rotors, and then when you transition, you turn on a cruise propeller. The problem with that sort of design is that you end up carrying quite a lot of parasitic weight, because each system is only designed for one phase of flight.

We iterated around that for a while to see what the pros and cons were, and then we looked at this tilt rotor concept, and we concluded that the tilt rotor was the most viable.

These things are incredibly sensitive to weight. They're not like conventional aircraft. Weight is so, so, so critical, so to eliminate that parasitic weight, the tilt rotor concept shone through to us.

OK. And you've gone with an interesting configuration there, with two banks of rotors. One bank is tilt-capable and the other can fold up. What do you call the way those rear rotors stack up?

We have a scissoring mechanism. In conventional flight, they'll stow, if you like, into an aligned position, and be parked to reduce aerodynamic drag from those rear rotors when we don't need them in the cruise configuration.

In an ideal world, we'd like to eliminate those rotors and do everything with tilting rotors, but the size of the rotors just gets too big, and if you increase the number of them, the weight you're carrying around gets too big as well. There's a delicate sweet spot in trying to sort these configurations out.

Yeah. I think the Joby aircraft, they're tilting all their rotors, they've got two on the back wing.

Yes, they have quite a lot of smaller rotors. We think they're probably carrying a mass penalty for that.

They've got six, four along the front wing and two along the back. It's fascinating to see how many different approaches there are. In most fields, you end up with a configuration that ends up killing everything else, but because it's so early in the eVTOL game right now, there's all sorts of ideas out there. In Joby's case, maybe they're carrying extra weight because of those tilting rear rotors, and that's a problem you guys are solving with these scissoring props.

There's so many things that are going to define success in this industry. Useful range, payload capability, and to open up the market, noise has to be absolutely nailed.

We're really trying to focus on noise in this aircraft. Our working example is that initially we think these aircraft might displace conventional helicopters.

In London, there's a heliport at Battersea, and it's limited in flight numbers per day, purely because of noise regulations. We're targeting an aircraft that's something like 30 times quieter than a conventional helicopter. If we can get that kind of noise reduction, it really opens up that heliport for far more use. That's one of our first use cases that we're pursuing.

Right. So one of the drawbacks of a tilt rotor design is that things get a bit crazy in terms of the flight dynamics when you transition between those modes. I note you guys are hooking up with Honeywell for your flight control systems, that's a name I'm starting to see pop up around a few eVTOL applications. What can you share about what they're up to with eVTOL flight control systems?

Honeywell is putting a lot of emphasis on this new urban air mobility market. They're putting a lot of focus on it. They've developed a rather neat-looking flight control system that's very small and compact, designed specifically for this sort of market.

We've worked very closely with them to optimize our system. We have a system test bench in our facility in Bristol where we're simulating the page of the flight control system, and response to various inputs, and the motions of the actuators and that sort of thing.

I can't give too much away about what's in their system, but it's widely used, it's had a lot of use on military aircraft. I think it was designed initially for military aircraft, so it's very good at controlling complex flight systems.

Do you mean military tilt-rotor aircraft like the Osprey VTOL?

I'm not sure, I've got a feeling it might've been developed for one of the JSF variants, whether it was the F-35 or one of the others in the competition. I'm not sure.

But it uses what they call dynamic inversion technology, so it basically takes a model of the aircraft and looks at what happens to the aircraft under certain inputs, and then reverses it to tell you what sort of inputs you need to make the maneuver you're actually after. So it's quite a complex system.

So the idea for you guys is to keep the pilot controls fly-by-wire, very simple. Can you maybe talk about what the experience of flying one of these might be like?

Well, clearly we're hoping to have a pretty smooth passenger experience. We have no experience of actually flying one as yet, but we have what we consider to be a very realistic simulator put together for our aircraft, incorporating that Honeywell flight control system.

Our CEO Michael was in the office – clearly, we've been working under lockdown restrictions for quite a period of time, but Michael was in the office a couple of weeks ago and the guys were in there getting the simulator up and running, so he took the opportunity to quickly hop in and fly the aircraft.

Now, Michael's not a pilot, but he described it as incredibly easy to fly. Felt very natural, with minimal control inputs. Our focus is not to de-skill the pilot, but to reduce their workload as far as we practically can. And it seems from Michael's feedback, that might be the case.

We have a pilot that we work with quite closely, who's been helping to develop the simulator tool. He's been very complimentary, saying it's very easy to fly and very smooth.

OK! I wanna pick up on something in your press release about certification, that this is on track to become the world's first certified eVTOL. What do you feel gives you guys the leg up in that regard?

We've been working with the European regulators, EASA, for some time. One of the things we did early on was to engage with EASA to understand what their requirements would be in this field. This is back before they even realized this market was starting to develop.

So we've been working with them for quite some time. They've complimented us on our approach. They have said to us that they feel we're probably one of a handful of companies in Europe that has a credible route to certification.

EASA have subsequently issued a document that they call their special conditions for eVTOL. SC eVTOL. That was issued last year, and it sets out the conditions for eVTOL aircraft.

The requirements are commensurate with the safety requirements, for example, for a large passenger aircraft. We chair a number of the working groups that are consulting on these regulations, and are helping to define what are considered to be acceptable means of compliance against these regulations.

So I think we have a really good relationship with EASA. They know what we're doing, we're helping to shape the regulations and define levels of safety.

When I say they know what we're doing, for example, we had a big battery test last year. We got some cells in a battery pack, and did a drop test, and we invited EASA along to witness that test. It was a successful test. We also did a thermal runaway test, where we basically pointed a flame at the battery and let it burn to see what would happen. Again, they witnessed that test, and they were very complimentary of our approach to addressing safety and reliability in the aircraft.

So it's that openness, that relationship with the regulatior and strict adherence to their regulations that gives us confidence that we've got a clear route to certify the aircraft.

Do you have a sense for when the rule books will be written?

Well, as I say they've written the special condition, and it's been out for consultation. I think the consultation period has closed, so I'd expect the full set of regulations to be available, probably not this year but probably early next year. Certainly within the time frame that we're looking to certify in.

In the meantime, we're busying ourselves putting our organization together so we can apply for design organization approval, or DOA approval, with the regulator. That's another clear step towards certification, and as part of that journey, we recently passed through checkpoint two, which is one of their review checkpoints to approve us as a design organization.

That gives us confidence that we're on track to do this, to get things aligned and ensure we meet the regulations.

Right. One little safety issue that just keeps on pinging off my radar is what happens in a total failure during the vertical takeoff part of a flight. Some of these aircraft have ballistic parachutes, but they just don't work if you're not high enough. Do you guys have a solution for that? What are you looking at?

Well, what we're trying to do is to build in significant levels of redundancy into the system. So our aircraft will have multiple battery packs; you're unlikely to have al the battery packs failing at one time. You're unlikely to have all your motors failing at the same time. We designed the placement of the rotors in such a way that if a rotor were to fail, it's unlikely to cause a cascade failure on other rotors.

So while these failure cases can't be ruled out, we've tried to design the system such that the likelihood of those happening are incredibly low, in the order of one times ten to the minus nine. So that's a level of safety on par with or better than what you'd expect from a large commercial airliner.

In that scenario, you're going to struggle, but what we try to do is make the likelihood of that incredibly low.

OK. I've heard some fairly outlandish ideas off the record about how to deal with it, but redundancy seems to be what most companies in your position are pushing for.

That was one of the things we did with the Seraph last year, shutting down one motor during flight to understand how the rest of the system would respond. We designed the system such that in the event of a single rotor failure, the other seven can take up that additional eighth of the load. We designed the batteries so there's capacity in each battery pack to accommodate the failure of another, and the systems will swap over.

Speaking of batteries, I guess energy density being what it is with lithium, I'm questioning whether it's going to be commercially viable to go live with a lithium-powered eVTOL, even in four or five years, even if there are a couple of leaps in battery technology. The charging times are so long, the ranges are so short, the batteries are so heavy. Have you guys looked into hydrogen? I know there's a few companies pushing hard on that front.

Yep, we have. We continue to do so. I think, and it's just my opinion, that in the longer term that's likely to be where we end up. Either something hydrogen powered or more of a hybrid type approach.

Right now as we work towards certification, we're designing around battery technology that we know is available. But for a similar weight, a hydrogen fuel cell would increase our range by a factor of two if not more. So rather than looking at London to Brighton, which is the use case we put in our press release, we're starting to look at something like London to Paris.

So you can start looking at building a market around the big city pairs with hydrogen power. So it's something we're actively working on, and we want to explore whether we can drop that technology into our prototypes a couple of years down the line.

I guess if it's just a powertrain, you guys can prototype and certify on lithium, and then swap out the guts of it down the line.

(Laughs) Well, it's not quite that simple, but yes. That might be the an approach that we'd consider using.

It must be a very exciting little niche to be in at the moment. So much innovation going on, so many different solutions, the race to be first ...

Yeah! I've been at the company now about four months after a 33-year career at Rolls-Royce. When I was approached about this role, it was like do you want to design an aircraft that's never been done before, using technology that doesn't really exist, to fly in an airspace that people haven't really thought about using … what's not to like about it?

Yeah, it's an incredibly exciting arena to be fortunate enough to work in. And the pace of change is just phenomenal.

As somebody who's just covering this space, things are flying at us all the time, if you'll excuse the pun. It seems like every couple of months there's some brand new big idea.

There's some great solutions out there, and there's some weird and wacky ones out there too. I'm sure quite a few of these will fall by the wayside. We're just trying to set ourselves up as robustly as possible to make sure we're not one of them!

Absolutely! So 2024 is the target date?

Yep.

And at that point, the plan is to basically start replacing helicopter services. Will you guys be running your own service, or concentrating on selling airframes?

We'll be selling. We're hoping to be collaborating with a ride-sharing type service or somebody else who can put the infrastructure in place.

There are two immediate markets, the intra-city market – I'm not sure that the infrastructure will be in place for that market by 2024 – and the inter-city flights from one city to another. I think that market might be the first one that opens up, and that's where we anticipate we'll be able to displace conventional helicopters.

Clearly, we'll be ready for either, but I guess it's the pace at which the infrastructure gets developed – the vertiports, the airspace control systems, those sorts of things.

So Vertical Aerospace has no interest in getting its own app up and running and selling services directly. That's interesting, a lot of these other companies seem pretty keen on grabbing that, becoming the brand that people go to, maybe interfacing with ride share. Is it just a matter of simplicity for you guys?

I'd say it's sort of stick to your knitting, really! We see ourselves as an aerospace engineering company, that's what we think we're good at. There are other people far better and more qualified to do apps and infrastructure.

Fair enough, that covers most of the questions I had. Is there anything else you'd like to touch on while I've got you?

Nope, I think we've covered everything really. Obviously we're incredibly pleased with the response we've had to our announcement last week, and now we're busying ourselves trying to build an aircraft so we can get flying next year!

Cheers to that! Thanks so much for your time!

Source: Vertical Aerospace