Now this is the sort of application of AI that really intrigues me. Researchers have developed DolphinGemma, the first large language model (LLM) for understanding dolphin language. It could help us translate what these incredible creatures are saying, potentially much faster than we ever could with manual approaches used over several decades.

“The goal would be to one day speak Dolphin,” says Dr. Denise Herzing. Her research organization, The Wild Dolphin Project (WDP), exclusively studies a specific pod of free-ranging Atlantic spotted dolphins who reside off the coast of the Bahamas.

She's been collecting and organizing dolphin sounds for the last 40 years, and has been working with Dr. Thad Starner, a research scientist from Google DeepMind, an AI subsidiary of the tech giant.

With their powers combined, they've trained an AI model on a vast library of dolphin sounds; it can also expand to accommodate more data, and be fine tuned to more accurately representing what those sounds might mean. "... feeding dolphin sounds into an AI model like dolphin Gemma will give us a really good look at if there are patterns subtleties that humans can't pick out," Herzing noted.

Dolphins typically communicate with each other using a range of whistles (some of which are names), echolocating clicks to help them hunt, and burst-pulse sounds in social contexts.

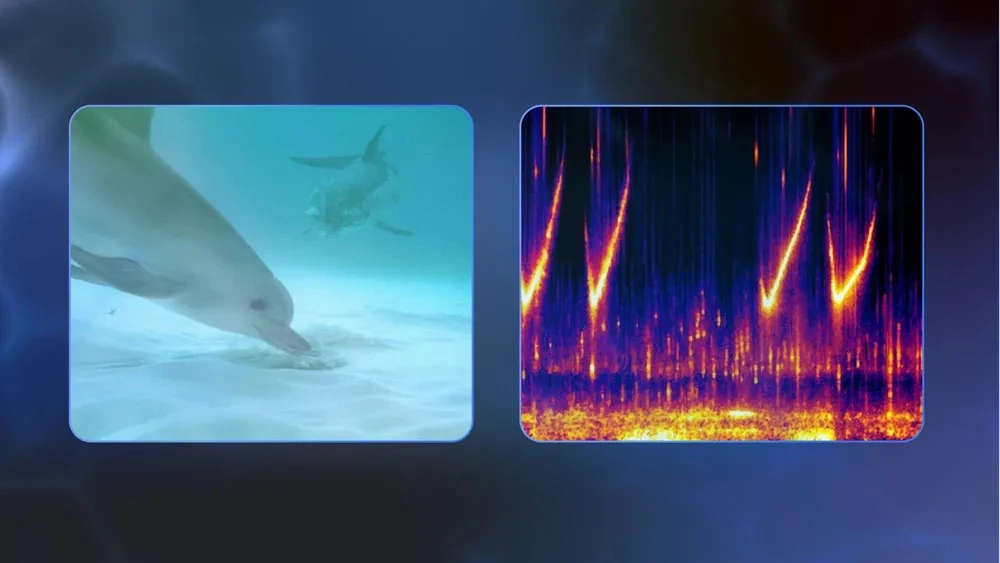

Since the 1980s, researchers have recorded these sounds using hydrophones (underwater microphones), analyzed them to find similar patterns with spectrograms (visual representations of sound that show how the frequency content of a signal changes over time), and then experimented with dolphins by playing those sounds back to observe their behavior. That's a whole lot of manual work to develop a catalog of dolphin sounds.

The team's LLM, which is built upon the foundational tech that powers Google's Gemini models and its popular chatbot, uses sophisticated audio tech to represent dolphin sounds as tokens. It's trained extensively on WDP’s acoustic database of wild Atlantic spotted dolphins, and processes sequences of the sounds they've produced to identify patterns and structure.

Google notes that it can practically predict the likely subsequent sounds in a sequence, similar to how you get suggestions when you're searching for something online or composing an email and need help completing a sentence.

Creating a secret language

What if we wanted to go beyond simply observing dolphins talk to each other, and see if we could communicate with them in a shared language? That's what WDP has been exploring in parallel for the last several years with Starner's help. He's not just an AI whiz, but also one of the pioneers behind the pathbreaking Google Glass wearable.

Previous rudimentary systems to communicate with these animals involved a large dolphin-nose-sized keyboard mounted to the side of the boat back in the 1990s. The idea was that the researchers would interact with the dolphins while passing around attractive toys, and play artificial dolphin whistles linked to each large key with a symbol on it. They imagined the dolphins might point at those keys to request toys. Here's what that looked like (starts at 6:43 in Herzing's TED talk from 2013):

Since that wasn't as interactive as the researchers hoped, they switched to an underwater keyboard they could swim around with. While it didn't exactly result in an actual back-and-forth, it did show that the dolphins were attentive and focused enough to engage in learning to converse. So in 2010, WDP began collaborating with Georgia Institute of Technology – where Starner is a professor – to develop new tech for two-way communication.

Together with Herzing, Starner created CHAT (Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry) devices to enable two-way communication with dolphins. These large wearables, built around an underwater computer, featured hydrophones to detect and record dolphin vocalizations, speakers to play artificial whistles in the water, and a specialized interface that divers could use underwater.

The system worked by detecting specific dolphin whistles and associating them with objects or concepts. Researchers could also trigger artificial whistles using the interface, essentially "speaking" to the dolphins using sounds they could potentially learn to associate with specific objects.

Since those early days, the team has been updating the hardware and incorporating AI in it. Using Google Pixel phones in their wearables, the researchers have been carrying out a similar routine as with the earlier CHAT system:

- Demonstrate an action to dolphins, like handing over a toy, and play a sound over the underwater speaker to associate with it.

- Use wearable gear to identify the mimicked sound made by the dolphins who observed this.

- Inform the researcher (via bone-conducting headphones that work underwater) which object the dolphin "requested."

- Enable the researcher to respond quickly by offering the associated toy, reinforcing the connection.

With a prediction-capable AI model at the heart of it, this system is designed to help the researchers react to the dolphins faster and more naturally. The use of off-the-shelf smartphones means CHAT now uses a lot less power, can be maintained more easily, and is smaller than the previous version.

Herzing's organization will deploy DolphinGemma this field season, and this new model should accelerate the team's efforts to study and document the behavior of Atlantic spotted dolphins. Google says it will make DolphinGemma an open model around the middle of the year, meaning that it will be more widely available to researchers elsewhere in the world. The company says it should be possible to adapt it for use with other cetacean species, like bottlenose or spinner dolphins, with a bit of fine-tuning.

"If dolphins have language, then they probably also have culture," Starner noted. "You're going to understand what priorities they have, what do they talk about?" That could give us a whole new perspective on how intelligent species in the animal kingdom communicate and how their societies operate.

Source: The Keyword (Google)