From penicillin to rapamycin, the route to discovering remarkable medicines has often been a fortuitous one. Now, researchers are hoping that another surprise find, once again linked to bacteria, can be harnessed for its medical potential and even be used to destroy cancer cells.

In a new study, scientists from the University of Queensland have found that the venom found in the bristles of the asp caterpillar (Megalopyge opercularis) can punch holes in cells in the same way that the sickness-causing E. coli and Salmonella bacterial toxins can.

Fascinatingly, the asp has retained this molecular hole-punching trait for more than 400 million years, after acquiring it through a transfer of genes from bacteria. In evolutionary biology terms, it suggests it's a powerful survival mechanism worth holding onto for the species. Now, it could also prove mighty for us, with the potential to use these toxin behaviors to produce cancer-killing treatment and more.

“Toxins that puncture holes in cells have particular potential in drug delivery because of their ability to enter cells,” said Andrew Walker from the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland (UQ). “There may be a way to engineer the molecule to target beneficial drugs to healthy cells, or to selectively kill cancer cells.”

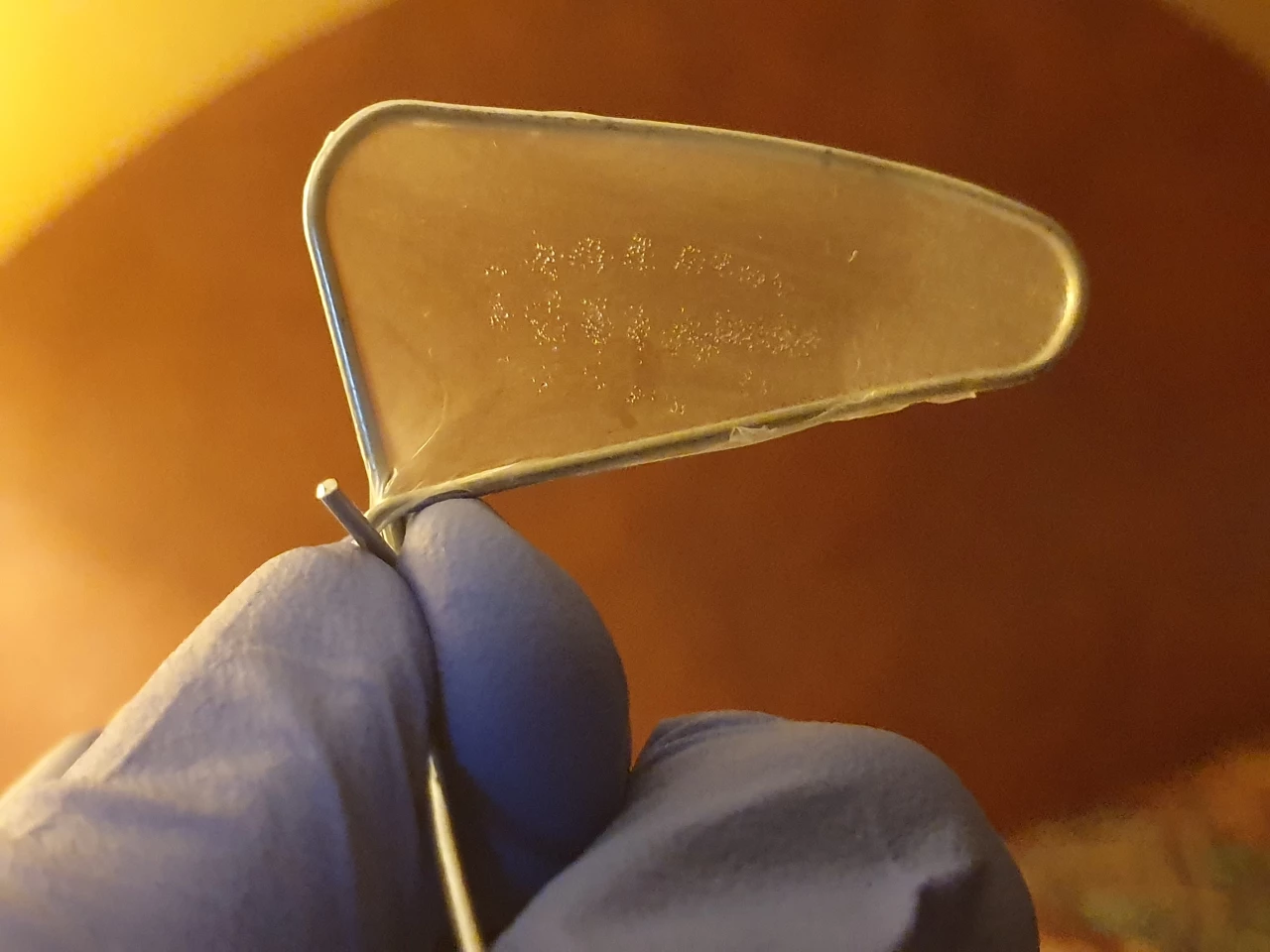

The asp caterpillar, which has many common names and has even been jokingly called the Donald Trump caterpillar, is the larval form of the Southern flannel moth and is found across the US, predominantly in the southern states. And it packs a painful sting, delivered by its skin-piercing venom barbs hidden among fuzzy-looking bristles. The side-effects of the sting vary, from a very unpleasant burn-like caterpillar-shaped mark, to more severe reactions that have seen people present to the emergency room.

“Many caterpillars have developed sophisticated defenses against predators, including cyanide droplets and defensive glues that cause severe pain, and we’re interested to understand how they are all related,” Walker said.

Walker, Professor Glenn King and a team from the Institute for Molecular Bioscience believe that the way the toxin acts – much like the illness-causing bacterial toxins, which bind to the surface of a cell and form donut-like structures that puncture holes – has huge potential for medical use.

What’s more, it opens the door to much more research, with caterpillar venom particularly understudied compared to snakes and spiders.

“We were surprised to find asp caterpillar venom was completely different to anything we had seen before in insects,” Walker said. “Venoms are rich sources of new molecules that could be developed into medicines of the future, pesticides, or used as scientific tools.”

This research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

See the caterpillar in action, and a rundown of the study, in this video below.

Source: University of Queensland