The existence of orange cats dates back to at least the 12th century, but scientists have only had theories that a sex-linked genetic mutation is behind it. Now, new research has pinpointed the exact variant, and it involves a gene that has previously been unknown to impact pigmentation in animals. So while there are other orange-colored mammals, the ginger cat is one of a kind.

Researchers led by Stanford University, with a simultaneous study undertaken by scientists at Japan's Kyushu University, have cracked the code on what appears to be a one-of-a-kind pigmentation mechanism exclusive to cats. At Stanford, the team looked at 51 potential variants on the X (female) sex chromosome that male orange cats had in common, and was able to narrow it down to three, then one. This one variant, which appears as a deletion that causes a nearby gene to over-express, essentially serves as a switch to produce lighter features instead of the default brown or black fur color – which presents as orange in male individuals with this mutation.

“In a number of species that have yellow or orange pigment, those mutations almost exclusively occur in one of two genes, and neither of those genes are sex-linked,” said Christopher Kaelin, a senior genetics scientist and lead author of the Stanford paper.

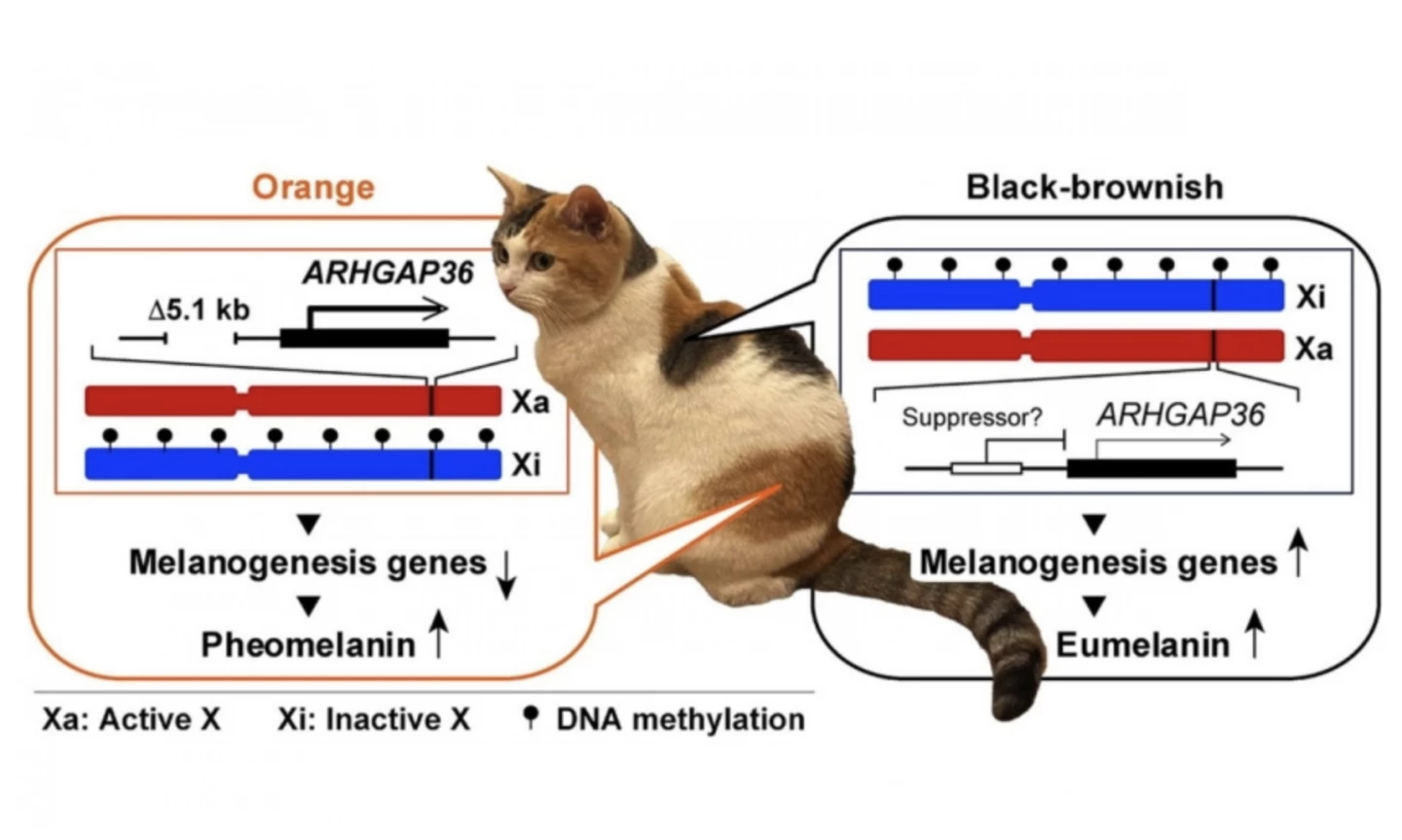

The scientists found that in orange cats' melanocytes – the pigmentation cells – the gene ARHGAP36 was more active, and all had the missing piece of code. And this gene was in turn instructing those melanocytes to produce the lighter features, including the ginger coat.

“Identifying the gene has been a longtime dream, so it’s a joy to have finally cracked it,” said Professor Hiroyuki Sasaki, lead author of the Kyushu University study – a cat lover and geneticist at the school's Medical Institute of Bioregulation.

Without getting too deep into the genetics, the X chromosome holds the code for black or orange pigmentation (white is driven by another mechanism). So a male cat (XY) with the variant can be entirely orange, yet female cats (XX) are incredible unlikely to inherit this mutation on both sex chromosomes. As such, they can have orange patches, while male cats will be orange or not orange, and no in between. This is also why calico and tortoiseshell coat colors – the two cat coats with some orange – are almost exclusively female.

“These ginger and black patches form because, early in development, one X chromosome in each cell is randomly switched off,” explained Sasaki. “As cells divide, this creates areas with different active coat color genes, resulting in distinct patches. The effect is so visual that it has become the textbook example of X-chromosome inactivation, even though the responsible gene was unknown.”

"This is something that arose in the domestic cat, probably early on in the domestication process," said Kaelin. "We know that because there are paintings that date to the 12th century where you see clear images of calico cats.”

Why it took so long to pin down is a good example of how slow science moves in general. Until half a decade ago, researchers didn't have the technology – including genome mapping and better DNA analysis – to produce a definitive answer. And this also makes it a very interesting period in research, as we see how machine-learning will advance often laborious and time-consuming genetics work.

“Our ability to do this has been enabled by the development of genomic resources for the cat that have become available in just the last five or 10 years,” Kaelin said.

The discovery of this ARHGAP36-activation mutation was a surprise, too – the gene is normally expressed in neuroendocrine tissue and can be a driver of tumors. Scientists didn't know it was active in melanocytes.

“At the time we found it, the ARHGAP36 gene had no connection to pigmentation,” Kaelin said. “ARHGAP36 is not expressed in mouse pigment cells, in human pigment cells or in cat pigment cells from non-orange cats.

“The mutation in orange cats seems to turn on ARHGAP36 expression."

Fortunately for orange cats, the mutation is in a non-coding part of the DNA, which means while it influences ARHGAP36 expression, it doesn't directly code for proteins.

“This is key,” said Sasaki. “ARHGAP36 is essential for development, with many other roles in the body, so I had never imagined it could be the orange gene. Mutations to the protein structure would likely be harmful to the cat.”

As to what drives this mutation, unlike in wildlife where variants will evolve for adaptive purposes – think a herd of zebras and how their stripes can "jam" the visual channels of predators – the orange cat was probably a rare type that was then bred by humans into worldwide prevalence. As to whether this mutation also affects personality, scientists believe this is unlikely. While they can't rule out the existence of other variants, it would appear these "friendly agents of chaos" might simply be the result of them being male.

“The expectation, based on our observations, is this is highly specific to pigment cells,” Kaelin said. “I don’t think we can exclude the possibility that there is altered expression of the gene in some tissue we haven’t tested that might affect behavior.

“There are not many scientific studies of the personality of orange cats,” he added.

That said, ARHGAP36 is expressed in other parts of the body – including in hormonal glands and the brain – but more research will be needed to determine if it has any influence on behavior.

“For example, many cat owners swear by the idea that different coat colors and patterns are linked with different personalities,” said Sasaki, whose team's research was actually crowdfunded by orange-cat lovers. “There’s no scientific evidence for this yet, but it’s an intriguing idea and one I’d love to explore further.”

The research was published in two papers, one from the Stanford team and one from Kyushu University, in the journal Current Biology.

Sources: Kyushu University, Stanford University