In another potential aerospace application for 3D printing, Boeing has filed an application with the US Patent Office for a way to make artificial "ice." The company isn't planning on making novelty ice cubes for the first class passengers (yet), but has come up with a way of printing plastic and composite shapes that can be tacked onto the wings and other surfaces to simulate icing conditions. According to Boeing, this will help to streamline and reduce the cost of the aircraft certification process.

If you've ever been out on a clear winter morning, you may have seen the trees and grass covered with a glittering display of ice crystals. These are produced when supercooled water droplets touch a solid surface and suddenly crystallize. On a meadow, this process is charming and begs for a decent camera. On aircraft, it's a deadly hazard as the ice builds up into mounds on the leading edges of the wings, degrades the aerodynamics of the plane, and increases the risk of a fatal stall.

Because of this, the US FAA and other national and international aeronautical bodies require that all new aircraft be certified to operate safely in ice conditions. This is done by taking the candidate aircraft and placing it inside a supercooled wind tunnel, where the plane's surfaces are allowed to build up masses of ice. These are then measured and reproduced in glassfiber and resin, which is roughened to the same texture as ice, and then mechanically attached to the aircraft. With these artificial ice shapes, as they are called, bolted on, a pilot then takes the plane up to show that it can still function under this unpleasant load.

Boeing says that this process has a great many drawbacks. It's slow, costly, imprecise, doesn't allow for control of important variables, and can damage a very expensive aircraft. The company's answer is to introduce 3D printing into the testing to create artificial ice shapes out of resins and other materials that are tailored to the specific airplane and to answer specific questions.

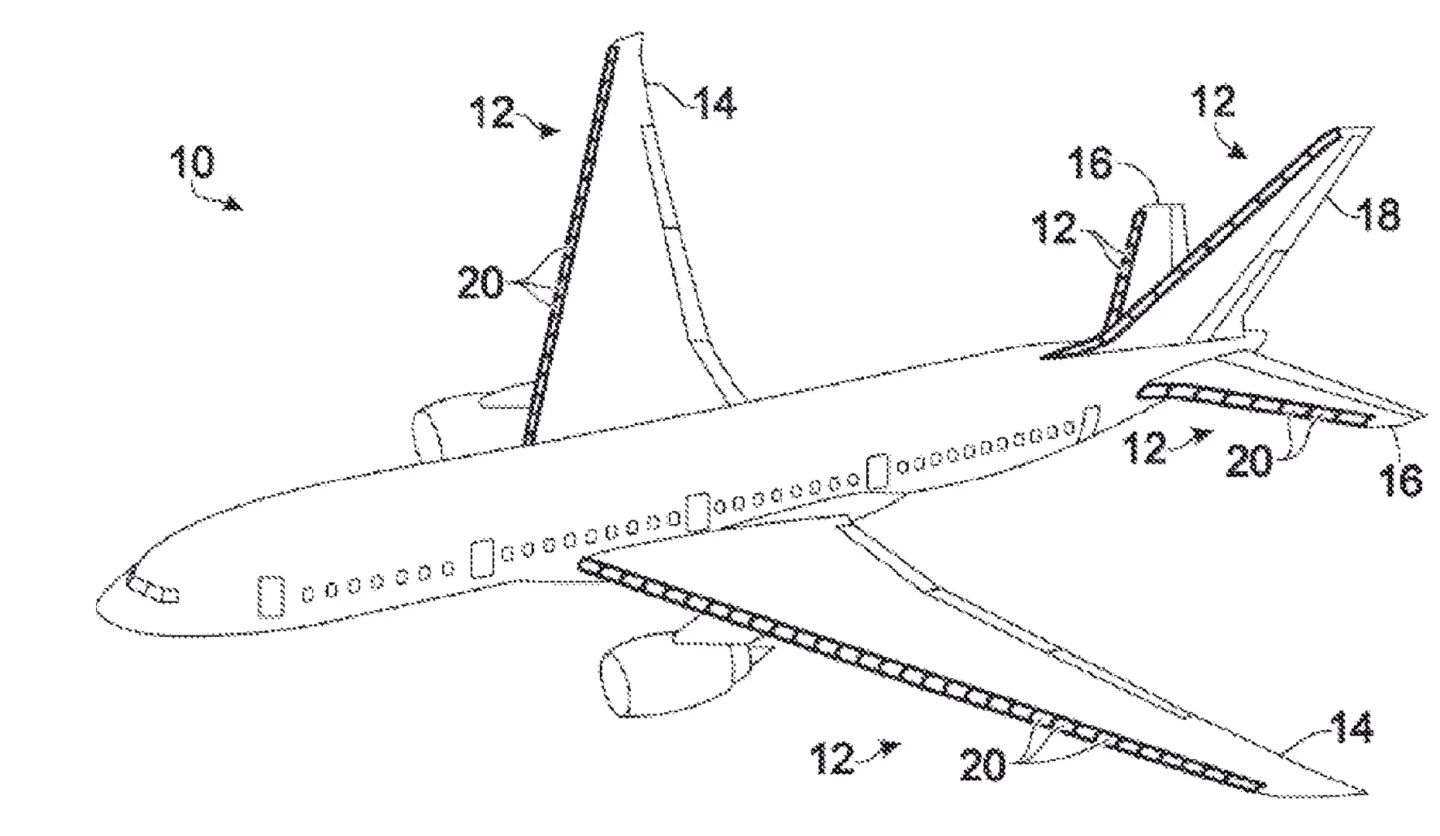

According to the patent application, the production of the artificial ice begins with a computer model of the aircraft. The shapes are designed to fit precisely onto the airfoil surfaces, where they are attached to the leading edges of the wings, stabilizers, and rudder using a double-sided adhesive instead of bolts. This not only creates a firmer hold, but disrupting the adhesive lets the shapes come away easily after the tests are completed.

The ice shapes themselves are designed in a computer, assigned various properties, such as density and texture, then built up in the CAD files in a series of layers to produce a complex interior structure that mimics actual icing conditions. These can be replicated at will from the files, so there's a much greater degree of control. The ice shape can be of a desired thickness, rigidity, or whatever else is needed to assess the aircraft's ability to cope with various conditions.

Boeing says that the shapes can even be printed with identification codes and markers to make sure they're put in the right place and line up properly. The entire process is based on a high-level flowchart designed to reduce the fabrication to digital files that can be plugged into any number of 3D printing methods using plastics, metals, composites, or other materials as the medium, either by additive printing, milling, or a combination of the two to create the final shape.

Source: US Patent Office via Aeropatent