Researchers at the University of Bristol have formed a company to commercialize highly efficient diamond-based betavoltaic battery technology that turns nuclear waste into a self-sustaining energy source – one that can last for potentially thousands of years without ever needing a charge.

The concept is this: you take particular types of nuclear waste from nuclear power stations – specifically parts of the graphite moderators and reflectors that have been exposed to fuel rod radiation and that have themselves become radioactive in the form of carbon-14.

Carbon-14 is a reasonably safe type of nuclear waste; it emits mainly beta particles, or high-energy electrons, and these don't get far or penetrate into skin. These electrons can be harvested to produce electricity, and instead of placing a collector near the sample, the Bristol team developed a process to convert that carbon-14 into a diamond form.

A carbon-14 diamond, it turns out, can basically generate and collect charge in one spot, greatly reducing the loss factor experienced if those beta particles have to travel any distance. It's also an excellent heat sink, and diamond's ultra-rigid structure and unbeatable hardness also gives you a high degree of mechanical safety because very little can break it.

The next step is to stack up lots of these carbon-14 betabatteries into cells, which could provide a constant power output. Where high power discharge is required, each cell could be accompanied by a small supercapacitor. The C14 diamond will fill up the supercapacitor with a trickle charge lasting potentially thousands of years, and the supercapacitor could offer an excellent quick-discharge capability due to its high power density.

These batteries won't give you an everlasting phone, or charge-free electric car, mind you; the quantities of energy generated are far too small. Instead, they have outstanding potential in a range of low-power devices and sensors, or higher-powered devices that draw power very rarely.

We spoke with with Morgan Boardman, an Industrial Fellow and Strategic Advisory Consultant with the Aspire Diamond Group at the South West Nuclear Hub of the University of Bristol.

He is also – and this is much less of a tongue twister – the CEO of a new company called Arkenlight, which has been created to commercialize the Bristol team's diamond battery technologies, among other radioisotope-driven power sources.

We present an edited transcript of the full interview below.

Loz: I thought I should reach out to you guys to ask what your thoughts are on what these devices are are capable of, how it works, what the limiting factors might be and a realistic expectation for where this might go commercially.

Boardman: Well, carbon-14 diamond material, in and of itself, has a limit on what can be produced in terms of electricity. That's from the diamond lattice itself. Once you begin to look at energy harvesting, capacitance, how the diode is structured, there are scalable possibilities as to what one could do, but they're still only going to be within a limited range.

But we're still very excited for a number of reasons. You mentioned the University of Bristol, and the University developed the patent which allows for the implantation or infusion of radionuclides into a diamond material. This is a game-changer for one reason specifically: up until now, betavoltaics have always relied upon a discrete radioactive source and harvesting capability. The radioisotope has been separate from the harvesting mechanism over there.

Even if you put them right next to one another, as the Russians did with the nickel-63, you still had a minor gap in between. And that gap, considering the extraordinarily short distance that beta particles can travel, gives you a huge drop in efficiency.

So you have several choices. You can go with a much stronger isotope source, which of course obviates the ability of humans to use them unless they're very well trained and it's a highly regulated environment. Or, and this is what we hit upon – and it was almost accidental – you can incorporate the radioisotope directly into the harvesting mechanism. That's what we've done, and that's what we've patented. We've had that patent published.

The second thing is that this is a major game changer. We now have efficiencies where this becomes commercially relevant. It would still be considered a microbattery, but say for example, 200 microwatts. That's how much energy is needed to power a pacemaker.

One could not power a defibrillator, because that requires a burst of sudden energy, a long way beyond what a pacemaker does. Pacemakers monitor pace, and it's a lower impulse. Defibrillators require a lot of energy, right now, and even with a capacitor, if somebody was having a major issue, it wouldn't recharge itself quickly enough to be ready to go again five minutes after you last used it.

In terms of actual use applications, we really see our first market for this as in connecting nodes within a mesh network, or along any kind of communication line, that provide data to create a contextually rich data environment.

The buzzword today is IoT. We're talking about creating industrial applications for, say, meteorological services, if they wanted to be able to measure temperature of ocean water at depth as compared to just at the surface. Right now they're using satellite hyperspectral imaging, and occasionally they send out a researcher to actually go out into the water, go down to a certain depth and collect a temperature.

But we could create mesh networks that could stay static, more or less, at depth, and give them consistent readings whenever they need them. We're also looking at applications for industry in, say, smart concrete. Or for security, being able to have a sealed tag and an RFID on a container that's persistent, and not dependent on any external power source. Assets that might be left under care and maintenance, say, specifically in the nuclear industry, they could be monitored from a security perspective – say, for the seal on the container – for a very long time.

And that's where we feel this will be really useful. And then, take the remote on your television. There's a consumer-based thing we could power. It doesn't take that much power when you press a button on a remote. This could be the kind of thing where you buy the battery, and hand it down through the generations. Here's great-grandpa's telly remote battery, kids. Try not to lose it behind the couch!

We consider it a multi-purpose technology within the microbattery market. If you look at microbattery applications, these serve almost all of them. I would also say, it's not just carbon-14. There are other isotopes which are perhaps better suited for applications that don't need a super-long battery life, and will spend a lot of time close to humans.

From the radiation point of view, these devices can be shielded so no radiation will reach the outside. But what's the potential impact of a particular isotope being leaked? With carbon-14, if that isotope was in, say, a gaseous state, it could bond with living beings and cause problems. That's in the worst possible case – in our application the C-14 is in the form of solid diamond so it can't be extracted and absorbed by a living being.

So we're extraordinarily cautious when it comes to humans and productization; safety is paramount. We would rather use something like tritium for products that are meant to be used close to people. Because hydrogen-3, tritium, passes from the human body very quickly, a few days max.

Carbon-14 also has a much lower capability in terms of the current it can produce. Tritium is energetically much higher, but it has a shorter life span. Its half-life is 12.5 years, compared to C14's 5,730 years. Let's say your requirement is 100 microwatts, and you want it to last 24 or 36 years. We'd just have to double or triple the mass of the device to maintain the current for that period.

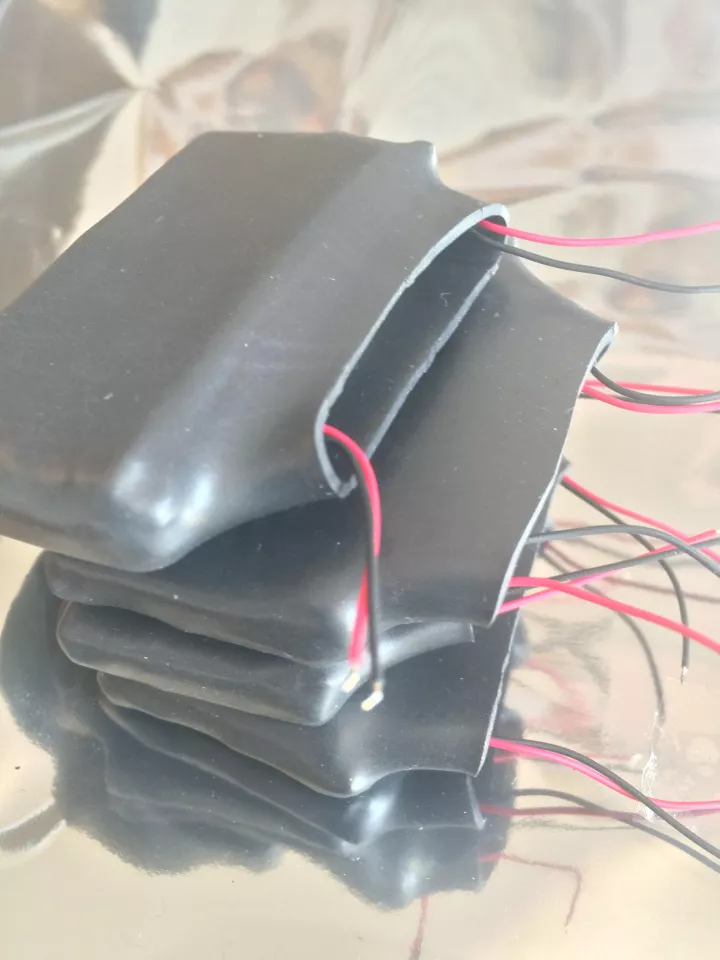

Another thing to consider is that we're talking about extraordinarily small batteries to start with. For a single microwatt, we're talking about something 4 mm x 4 mm (0.15 x 0.15 in) in width and length, that's very, very shallow. The size of a fingernail, but thinner. You can mechanically stack these in any number.

The thing I think that's really a differentiator for us is that the fit and forget aspect of this will be extraordinarily useful. As we've seen in the last six months, conditions in the world can be changeable and chaotic. Industry needs to persist and continue. We need businesses and services to continue, and I think a lot of people are looking at options now in the industrial IoT sector.

IoT was a buzzword six years ago, even 10 years ago, and it gained a lot of traction. It plateaued a bit as people who ran major companies started to find they didn't really know how to use this new tool. They didn't know how to fully utilize all the data they had.

Really clever ones did, but not everyone. And that's typical with new technologies. First there's the buzz, everybody wants it, then it flattens as everyone says "what am I supposed to do with it?" And then the magic happens, everyone understands it and it takes off.

That's where we're at right now in terms of this kind of application. People are intuiting that the world in its current status needs mesh networks with smart nodes that go to an edge controller, that can facilitate automation, that can facilitate an easier, safer, cleaner, more productive workplace for the humans that are interacting with it.

There are so many other ways to look at this as well, when it comes to protecting our environment, medicine, security as I said. I think we're going to see this mesa we've hit with adoption really taking off because of the conditions we're now facing in the world.

Already, Gartner and Deloitte had foreseen that the IoT sensor space is going to grow exponentially. There was one market report I read that assumed there would be an 11 trillion dollar market for IoT devices and sensors by 2025. That was as recent as last year, just before COVID.

I don't know how those forecasts have changed, but even if I take a very conservative look at it and say industrial IoT is going to be up to a trillion. How many of these things could be powered by either distributed power systems over node networks, or by a composite of our batteries together? Well, that'll decrease our possible market significantly. Maybe it's 10 percent of that. And we want to capture maybe 0.01 percent of that. So we're talking about a very modest approach.

So the real thing here is you're talking about a technology that was developed at the University of Bristol by some of the top tier professionals in the world, we have engaged a lot of engineers and physicists around us. We're working with a team of what I can say are very competent business professionals, who are very serious-minded and conservative. We have developed this into a business model that we're now commercializing with our partners both in government and in the private sector. I think that substantiates our claim going forward.

So can you give me an idea, for a given weight of carbon-14, what the constant power output might be?

Well, a device that's 10-mm (0.39-in) square, and less than 0.5 mm (0.019 in) in depth, would yield tens of microwatts. The amount of carbon-14 you'd need to power a cell phone would be about the size of a tub of vegetable spread. It can be done, but the physical bounds of carbon-14 diamond would require a mass greater than the phone itself. We do have some ideas about how to address this, but we're talking 20-50 years of additional research between ourselves and the electronics industry.

As I said, we could easily power small devices; that is, those that require less than a milliwatt in power. But one thing would come up: the cost would be significant. To use these for medical, IoT and security applications, they would have to be cost effective - space and military could cost more, but their needs are so specific that they would probably be willing to bear the cost in exchange for their challenging requirements being met.

Even if there were a significant breakthrough in capacitance capability, the physical bounds of the energy density per volume of C-14 would be a limiting factor that would make some things impossible unless one were willing to accept other limitations.

For example: claims by other contenders that they could power a cell phone or automobile, I would say yes – if the consumer is willing to have a battery that weighs more than the device being powered, in the case of energy-hungry devices.

Other companies seem ready to be optimistically euphemistic in their claims, but we've not seen a lot of proof in the pudding. We haven't seen photographs, we haven't seen proof of patents. We haven't seen anything consummated in the public about their relationships.

If you look at us, the UK's Atomic Energy Authority has, on their government website, pieces about how they're happy to be working with us on the battery product. That adds a credible weight. All I'm saying is we're substantiating our claims in this manner. So the challenge to others would be OK, talk is one thing, now let's see it!

Right. So Arkenlight. No website for us to link to for you guys?

No. We've been working together in pre-commercial development for the last year. Arkenlight currently consists of 12 individuals, three of us are businesspeople, there are three engineers and the other six are physicists. We've been working steadily and with a great deal of commitment on this. This doesn't include the allocation of resources the UK AEA has put forward, I believe they've spent a modest amount of money on allocating time from their engineers. Their staff have been very supportive, we've been working with them in our creative teams to define the business case as much as we can.

We've been on a roll as Arkenlight since early last summer, and there's a lot of boxes I had to tick before I could go out in good conscience and register Arkenlight as a business entity. I had a lot of stakeholders, this is a grand vision, it's going to be huge, so it substantiates a lot of back work to make sure it is, in fact, doable. We needed a validated business plan and proposition.

So we've got the ticks in the boxes and we reached a milestone recently. We registered the shell of Arkenlight to receive the IP from the University of Bristol, and also to place shareholders. For example, the AEA will be a minority shareholder to provide goodwill and link us together. The UK really needs some strong wins right now, and we anticipate we can deliver that, not only for the morale of the country but to drive the economy and create jobs.

But no, we don't have a website. [Editor's note: this is no longer the case] I try to be as impeccable as possible in my representation. I didn't want to put a website up until we were registered. I didn't want to register until we knew we could do what we were claiming we could do. So we're a little behind the gun on that. So it's a cart before the horse situation, we're putting the website together now. I guess we're being discreet about how we fundraise. We're not running around banging pots and pans and screaming into the bushes for people to give us money. We'd rather move quietly and competently than to showboat.

What's your timeline looking like?

In terms of when you can actually have one? Well, let's say you have a Toshiba appliance in your house that employs sensors, and those sensors are hard to reach, and you don't wanna have to replace batteries in them all the time, and they're not on mains and they need to have resilience in a power outage. Let's say that's the issue. The first time I think you'd have this Toshiba device in your house, with the sensors, with our battery in it, will probably be as early, I think, as the later part of 2023.

NASA uses what it calls a TRL, or Technology Readiness Level, from one through nine. One being 'this is just an idea I had in the bathtub, and I've scribbled it on the wall with my wife's lipstick' - that's TRL 1. TRL 9 is 'it's on a spaceship, it's out there in space, astronauts are using it, and it's done so well that we're putting it in instant packages you can use for a drink for your kids at home.' TRL 1 is a fantasy, TRL 9 is deployed.

I'd say we're at a TRL 4 with our carbon-14 battery. We've got a physical proof of concept, and we're validating, testing, changing and iterating through the experimental process to get us toward a serial prototype that would put us at TRL 6.

We have another product called a betalight voltaic, which is interesting in itself, and which we've been selling. So that one is a TRL 9. We've been selling them as batteries for sensor pods into the nuclear industry. This product uses tritium in a different way; it's not a betavoltaic device. Its form factor is significantly bigger than a tritium betavoltaic with a similar power output.

Betalight voltaics have been around for a while, but our branded version has a much higher power density than previous versions, and it makes up to 35 microwatts. This is our minimum viable early stage product, and we've already got it out in the marketplace. That one is in direct competition, say, with companies like Widetronics, Betabatt or Citylabs. Those are serious people, they know what this stuff is about and they've been doing it for a very long time.

And then there's the tritium diamond betabattery, which is a slightly lower TRL than the C-14 battery. After all, we were funded to produce the carbon-14 betabatt early on by the government. They had an early interest in that for applications in the nuclear sector.

But it's basically the same architecture, the same concept, it's just some minor differentiations in the technical application. We actually anticipate we might be out there even sooner with the tritium one then the carbon-14 one. That's the one we see as being the Holy Grail of what we want to put out in the market, based on what I talked about earlier in terms of power output and safety around living creatures.

So carbon-14 can obviously be converted into a diamond form, can you do the same with tritium, or am I missing something here?

You can. It's not the same process, but even still, we hold the patent on placing radioisotopes into diamond to generate current, and this process is also included in that patent.

We thank Mr. Boardman for his time and assistance.

Source: Arkenlight