Fourth Power says its ultra-high temperature "sun in a box" energy storage tech is more than 10X cheaper than lithium-ion batteries, and vastly more powerful and efficient than any other thermal battery. It's hoping to prove it with a 1-MWh prototype.

As a grid-level energy storage solution, Fourth aims to compete with big lithium battery arrays in the short-duration 5-10 hour range – basically storing excess solar energy during the heat of the day for use in the evening and at night when generation drops off. But the company says it's also relevant up to the 100-hour stage, which would cover the "several days of bad weather and poor renewable generation" case.

This is one of a number of thermal energy storage companies coming up out of Massachusetts and backed by Bill Gates's Breakthrough Energy Ventures fund. You might remember Antora Energy from a few months ago, with its ultra-hot carbon block batteries and high-efficiency thermophotovoltaic energy converters, for example.

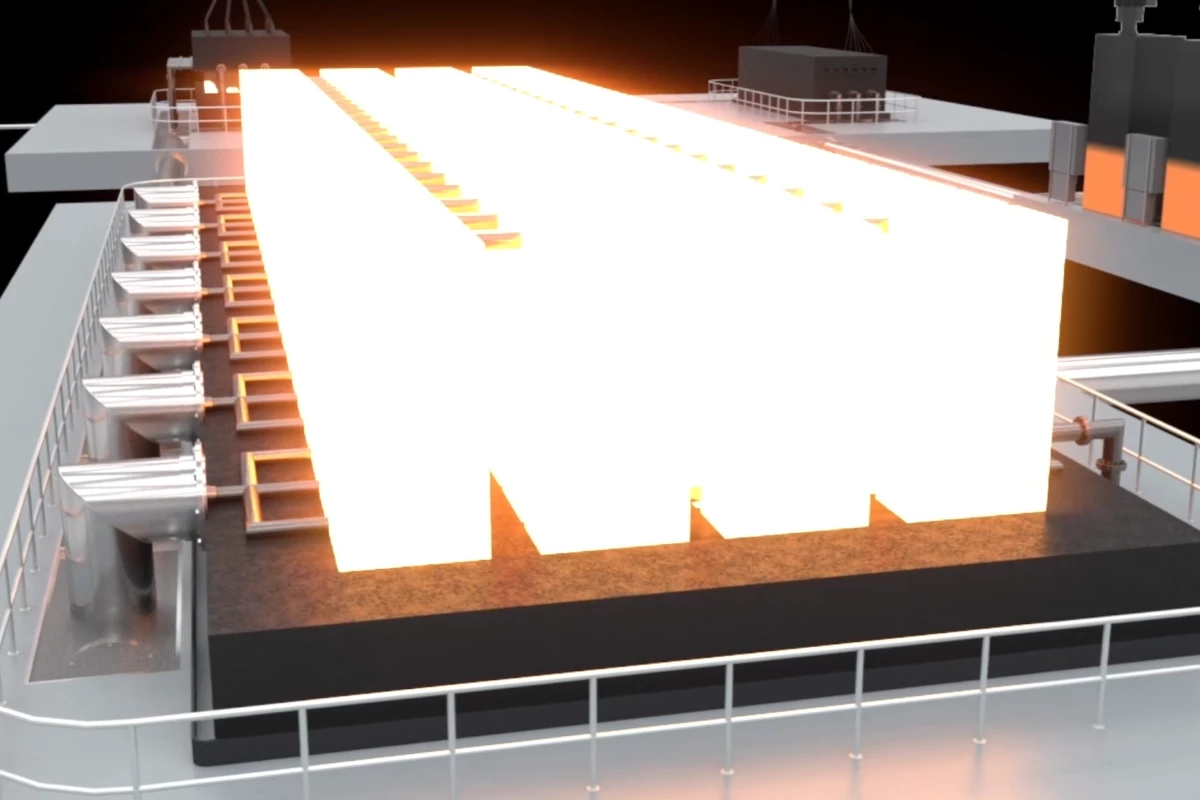

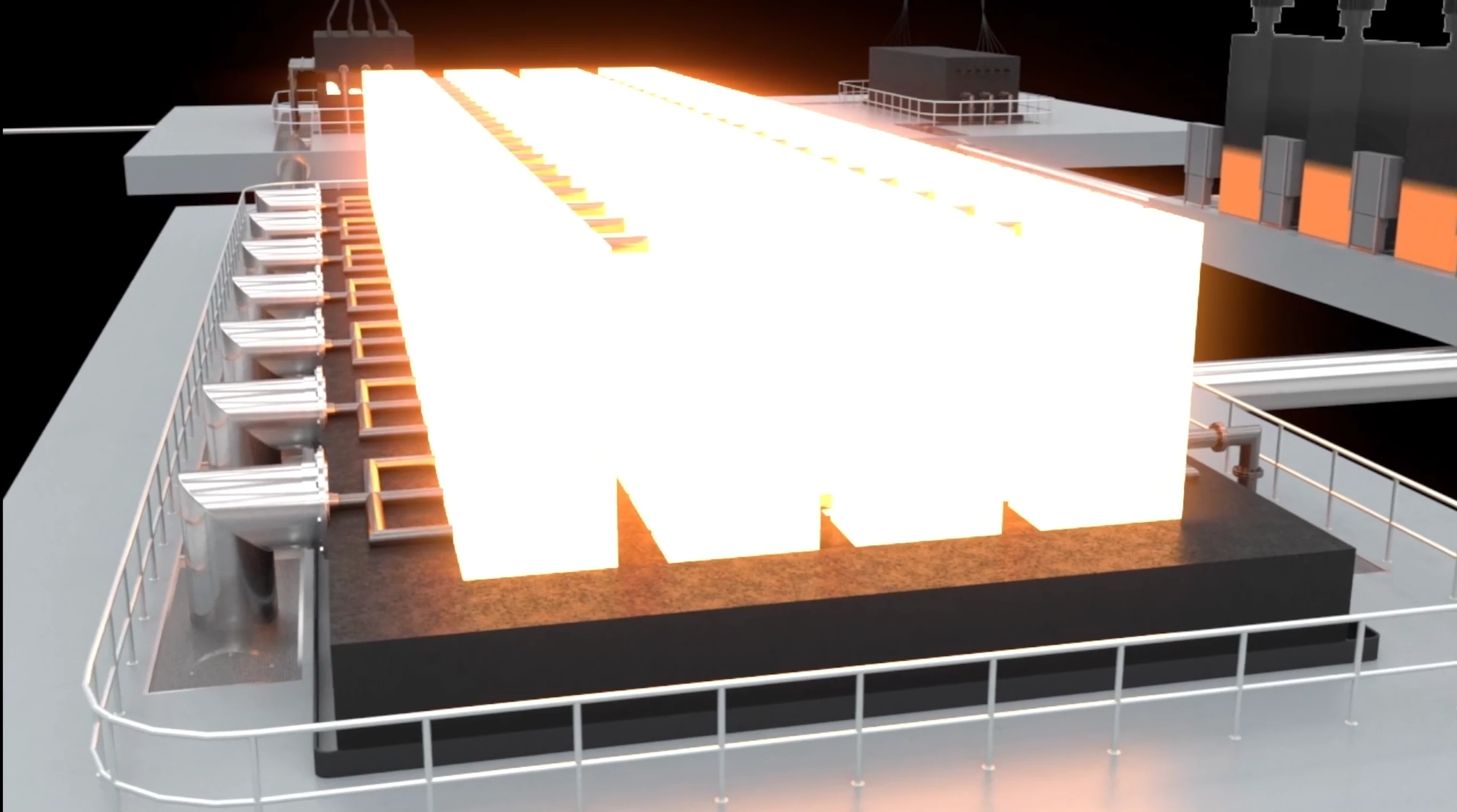

The idea is simple enough: you take excess renewable energy and use it to heat something up inside a heavily insulated storage system. Both Antora and Fourth use big, super cheap and abundant blocks of graphite for bulk energy storage – in Fourth's case, heating them up as high as a white-hot 2,500 °C (4,530 °F).

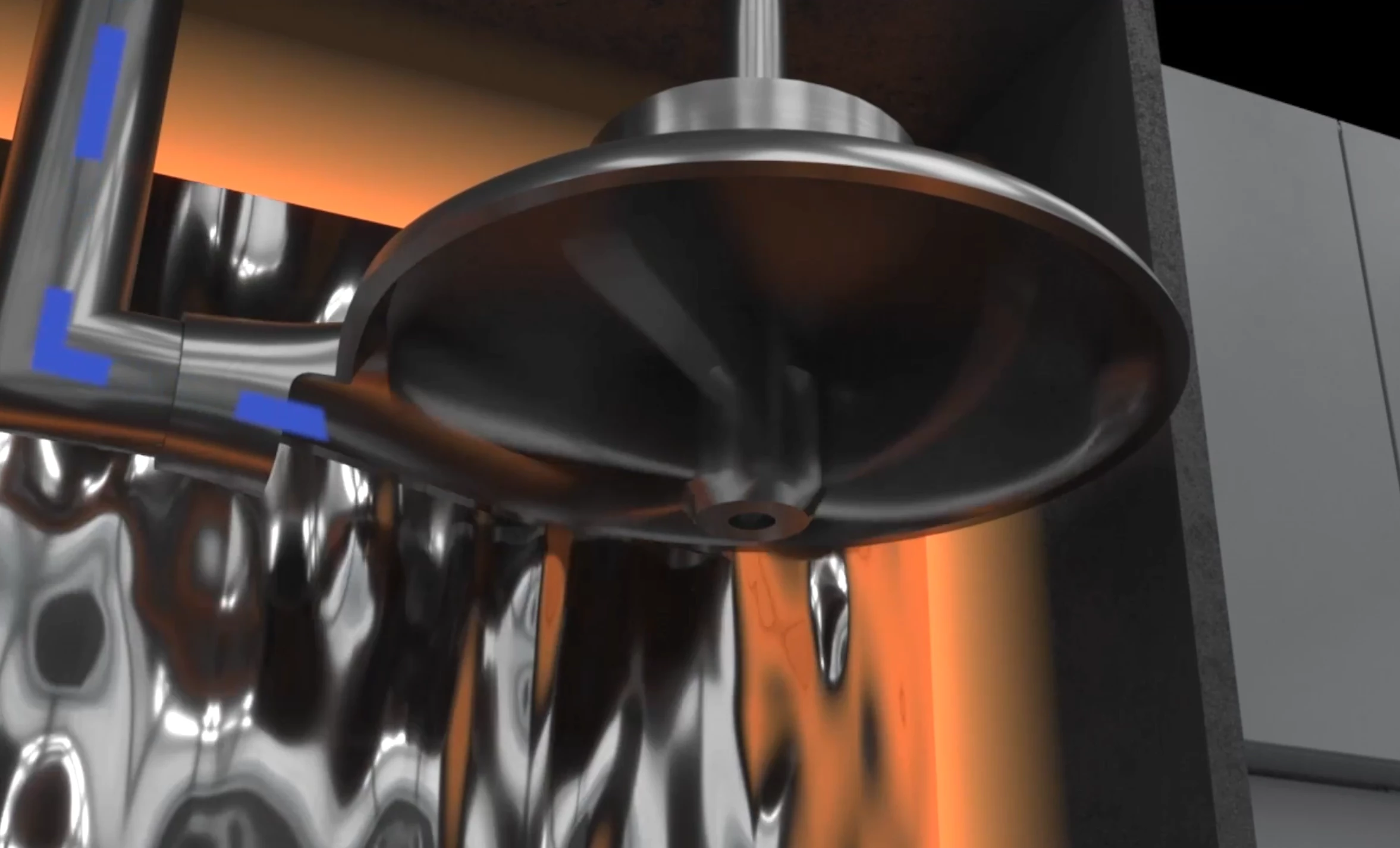

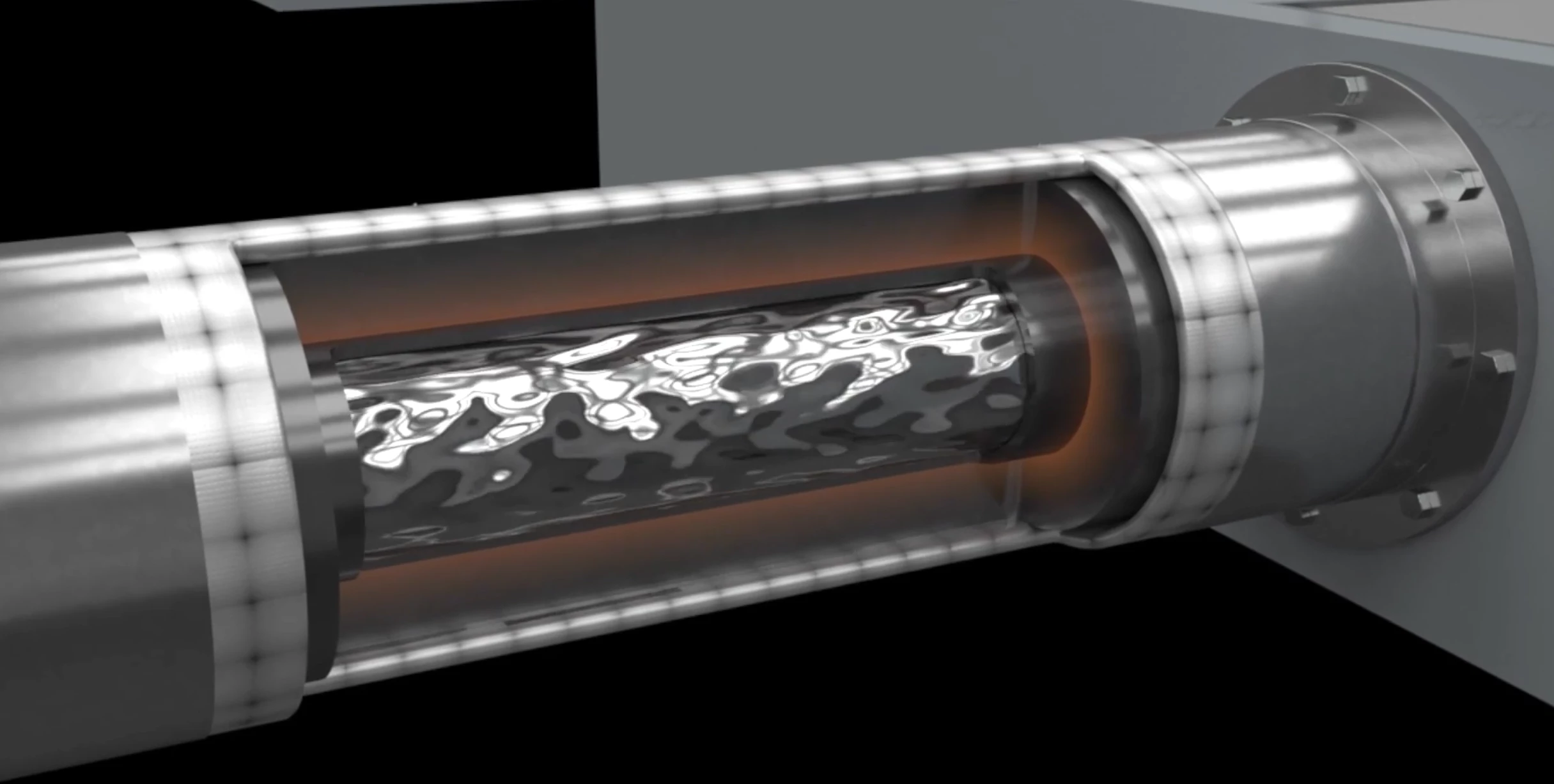

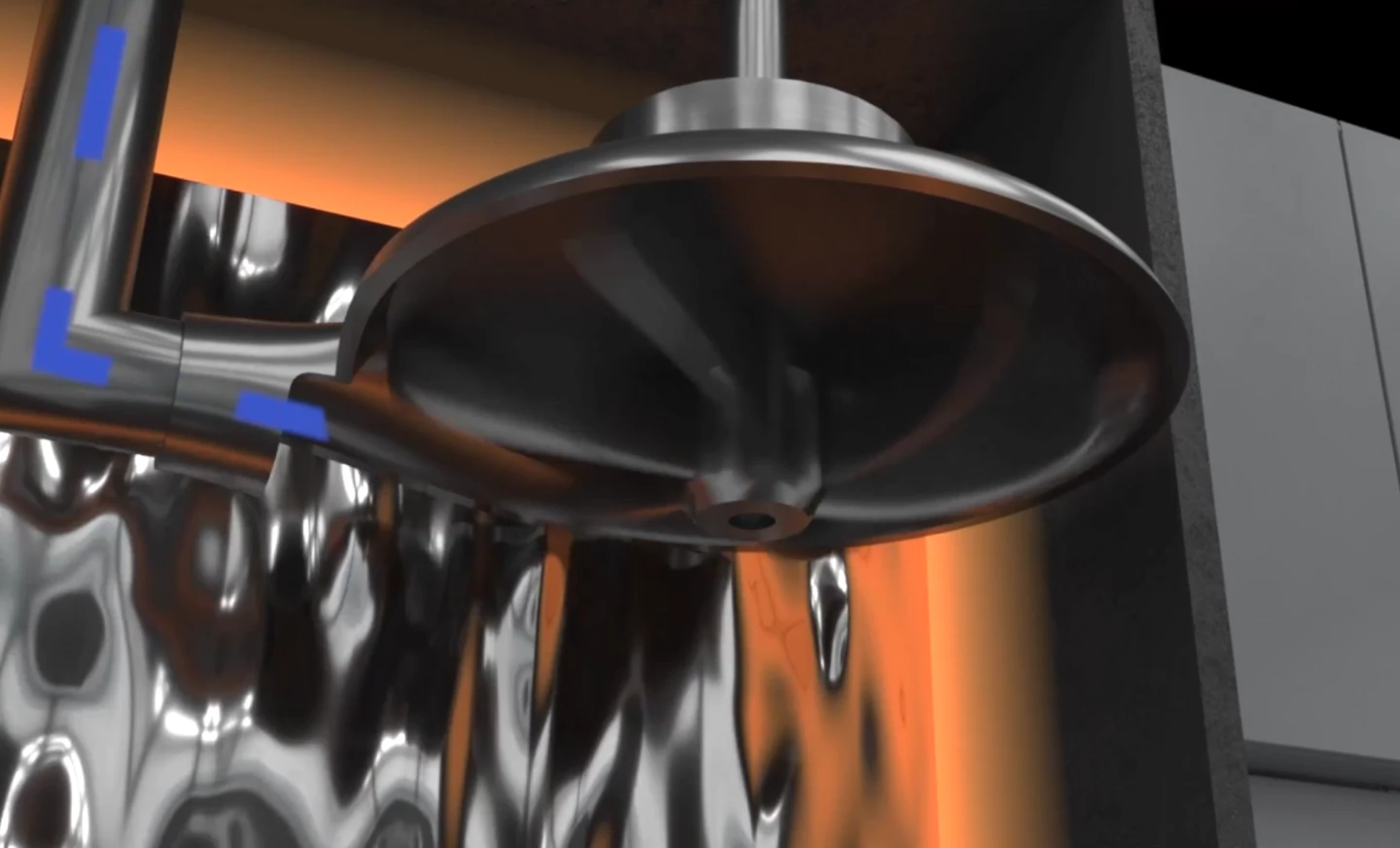

Energy is moved around Fourth's system using liquid tin metal, which melts at a relatively low 232 °C (450 °F). This is Fourth's secret sauce, and relies on a Guinness World Record-holding pump designed by founder Dr. Asegun Henry. At high temperatures over about 1,000 °C (1,800 °F), liquid metals can destroy metallic pumps, but Henry claims his engineered ceramic design will happily operate up to "almost half the sun's temperature" – we assume this refers to the 5,600-odd °C (10,000 °F) on the Sun's surface rather than the 15 million °C (27 million °F) at the core.

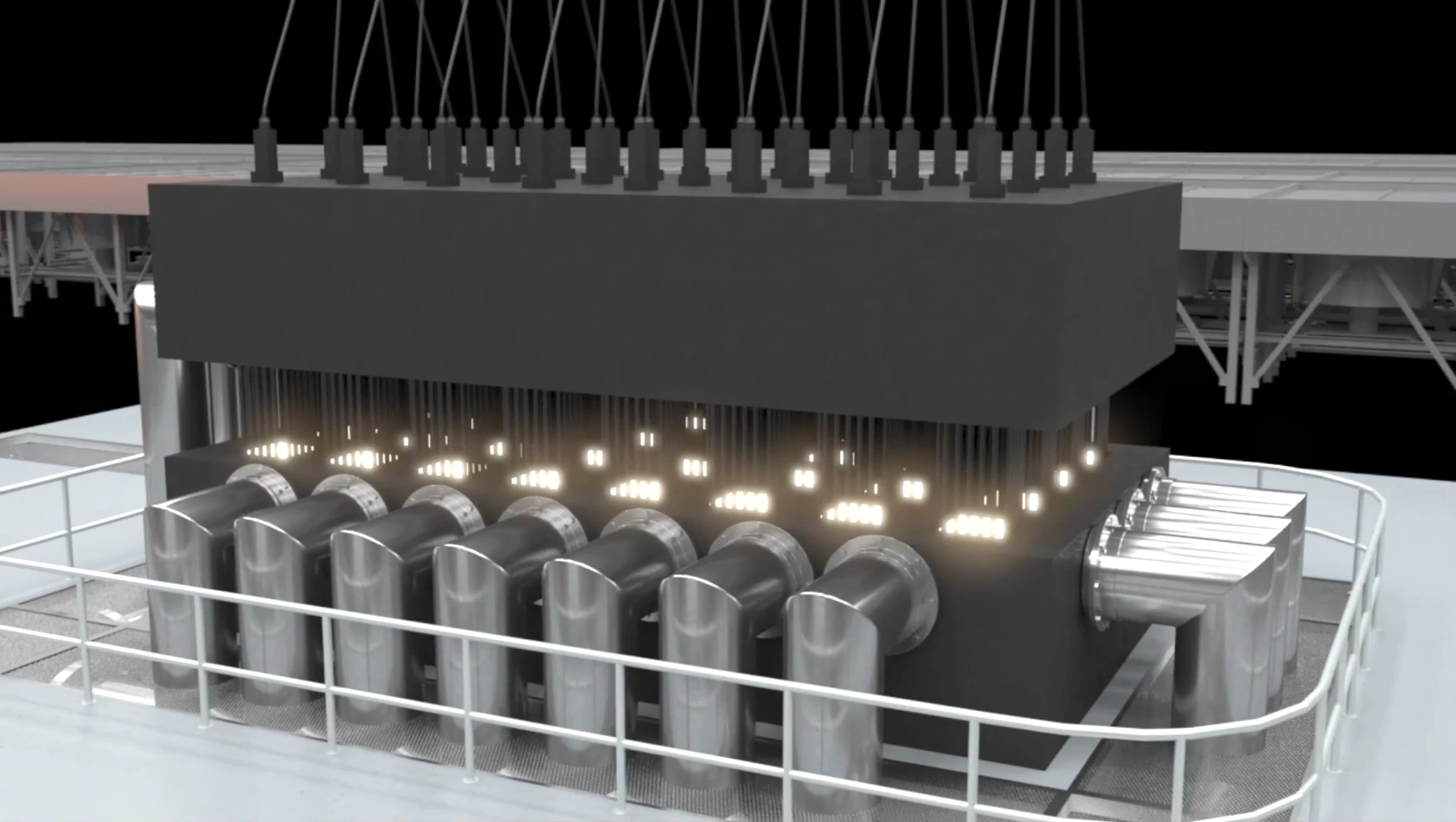

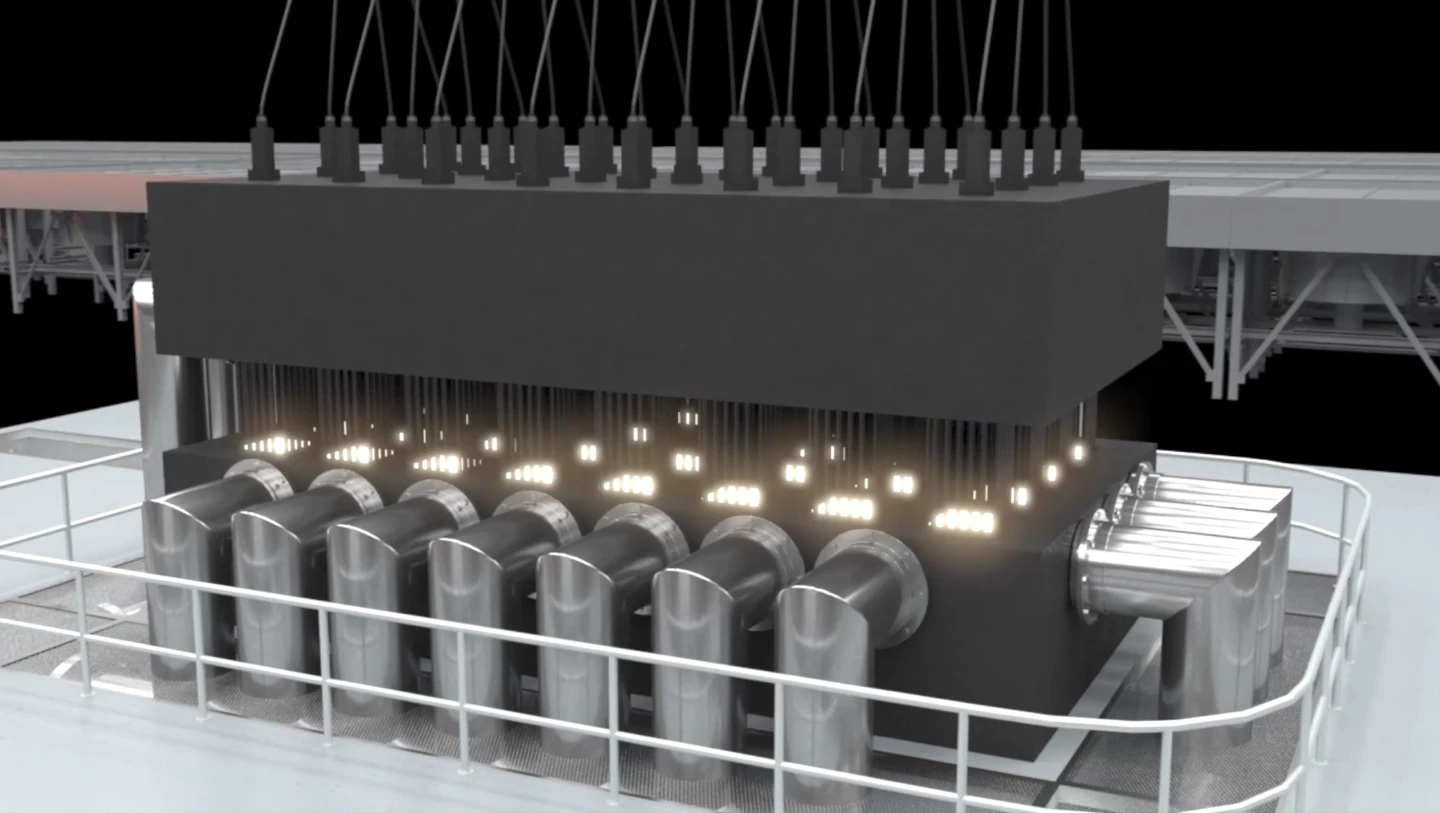

These pumps move the superheated liquid tin around a graphite plumbing system, transferring heat from the heating elements to the graphite blocks, and then taking it from the blocks to the energy recovery system when it's time to send it back to the grid.

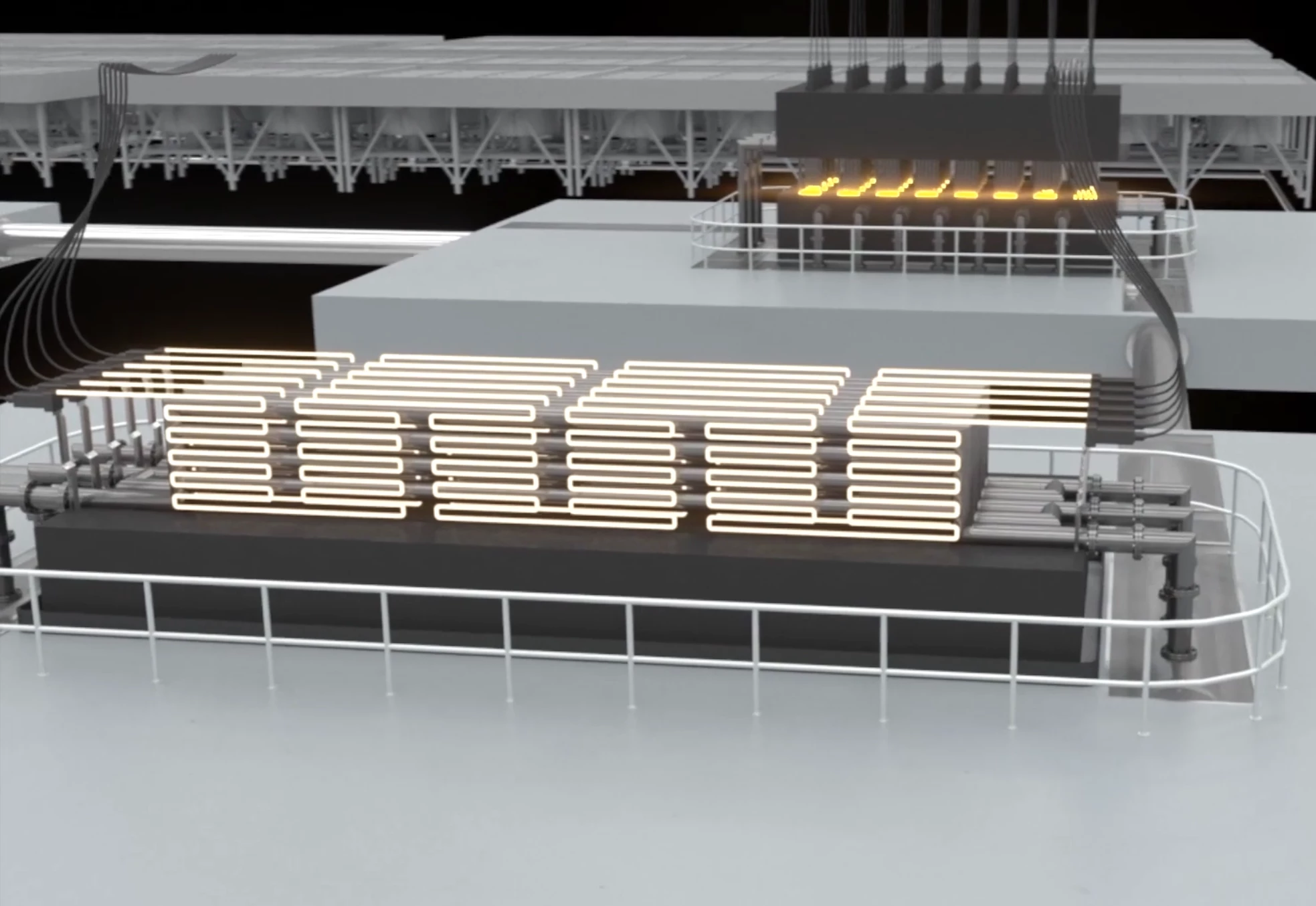

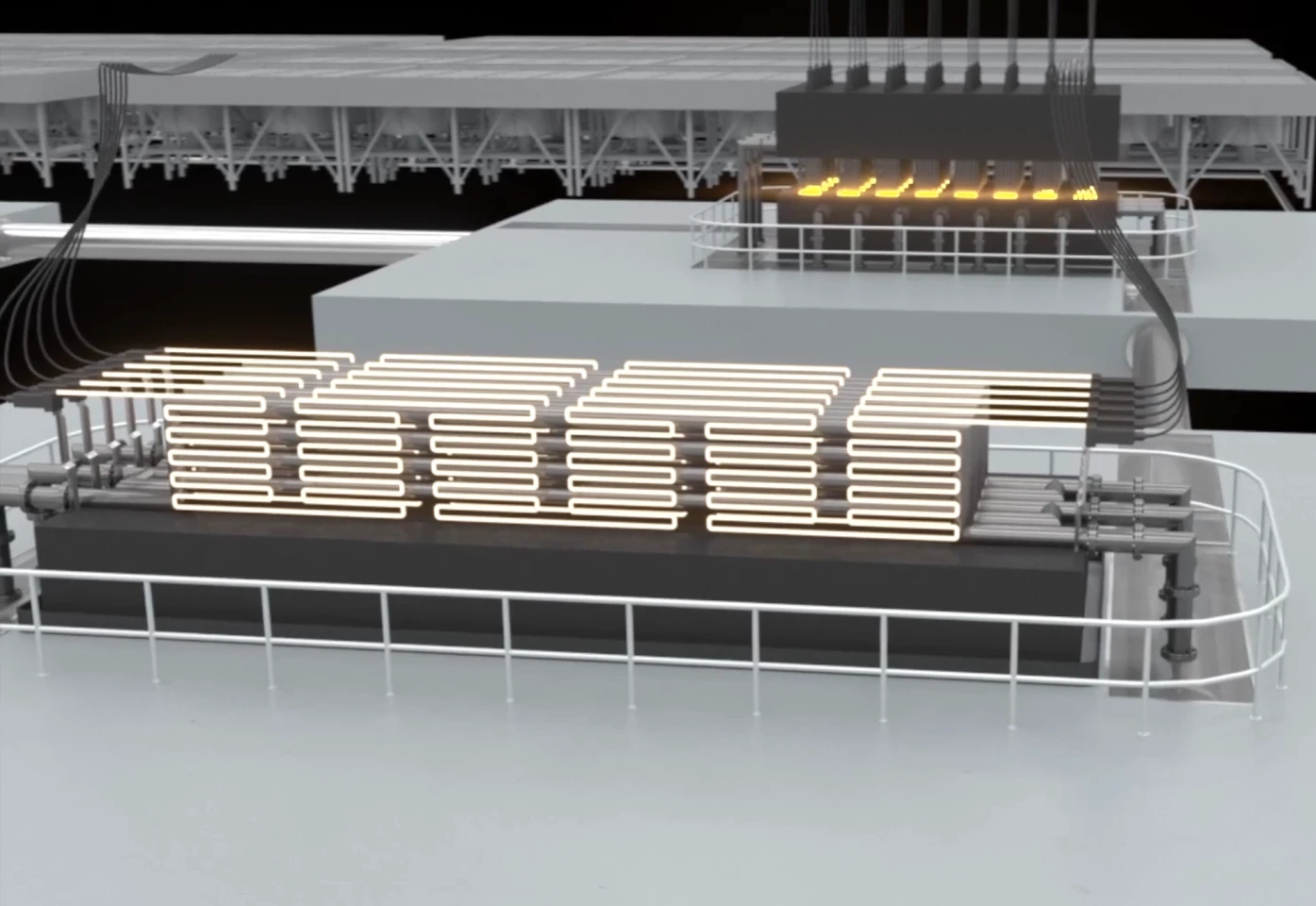

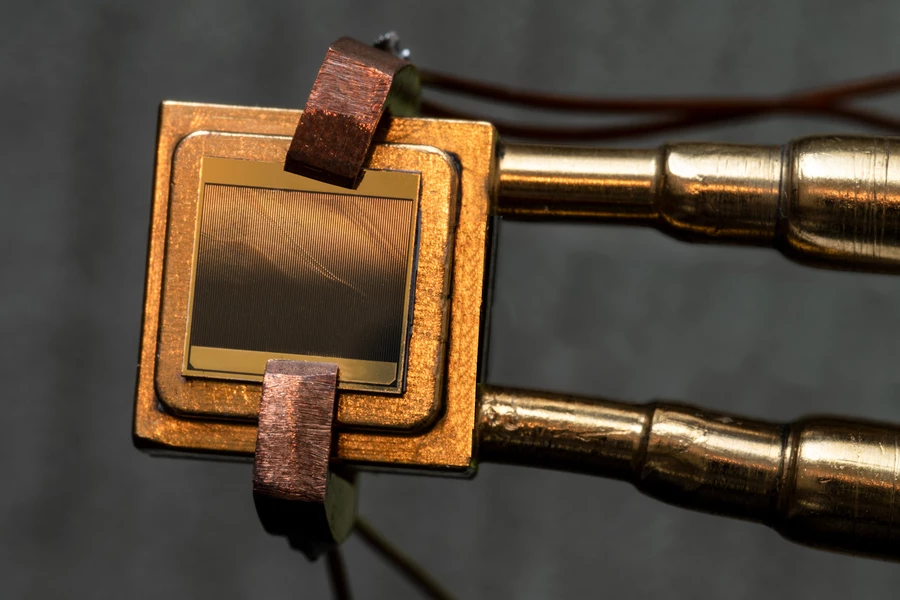

To recover the energy, the liquid tin is pumped through lots of narrow graphite pipes inside an array of power-harvesting cells. These pipes become white-hot and emit intense light, which is harvested through thermophotovoltaic (TPV) cells – much like solar cells, but tuned to work optimally with this storage system. At these temperatures, nearly all the heat transfer happens as light rather than conductive or convective heat, and these TPV systems are able to harvest energy using photovoltaic principles. Indeed, that's the major reason behind the company name; the light emitted by an object scales with the "fourth power" of its absolute temperature.

The TPV cells in question here are themselves pretty remarkable; we wrote about them last year, when Dr. Henry and his team at MIT announced a record-breaking thermal energy extraction efficiency, drawing more power out of heat than steam turbines. These cells only harvest the highest-energy parts of the wavelength spectrum, for optimal efficiency, and actual mirrors behind the cells reflect back the rest of the light to keep as much heat as possible in the liquid tin.

As the energy is harvested, the liquid tin drops from around 2,400 °C to 1,900 °C, (4,350 °F to 3,450 °F) and it's sent back to the heating elements to be "recharged" when energy is available.

The combination of that liquid tin pumping system and these high-efficiency TPV cells, says the company, combine to give you a thermal battery that's incredibly responsive, delivering energy back to the grid within seconds of a demand spike, and with an unprecedented power density, since the system can "transfer 10 to 100 times more heat than any other company with the same size equipment."

Fourth says it's aiming for a round-trip energy efficiency of around 50% from these thermal batteries – which is not great compared with the significantly higher efficiency of a big lithium battery array. It also appears to assume some pretty considerable development on the TPV side, since the record set back in 2022 was closer to 41%. And efficiency will be lower over longer-term storage use cases, in which it'll lose an estimated 1% of its stored energy per day.

But the power game is all about cold, hard cash, and here, Fourth says there's absolutely no contest. It's nearly all made of super-cheap graphite and tin instead of pricey refined lithium, so where a lithium battery setup might cost around US$330 per kilowatt-hour of stored and returned energy, Fourth claims it'll get the same job done for less than $25. So even if it'll throw away more electricity, the bottom line will still make it a financial no-brainer.

Oh, and it's safer than lithium too, since there's no chance of thermal runaway or explosion, and even if the liquid tin manages to escape the plumbing system, it'll simply freeze back into metal as soon as it reaches the insulation layers or concrete floor of the facility, which is filled with argon gas to prevent oxidation.

Recently, Fourth announced a $19-million Series A capital raise, with Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Black Venture Capital Consortium both participating. This cash will go toward a 1-megawatt-hour prototype facility near Boston, estimated for completion in 2026. So it's still a ways off, and it seems Fourth will hit the market a fair way behind Antora, which is already manufacturing its TPV cells and expecting to have thermal battery facilities operating commercially by 2025.

Source: Fourth Power via Recharge News