"We are sidestepping all of the scientific challenges that have held fusion energy back for more than half a century," says the director of an Australian company that claims its hydrogen-boron fusion technology is already working a billion times better than expected.

HB11 Energy is a spin-out company that originated at the University of New South Wales, and it announced today a swag of patents through Japan, China and the USA protecting its unique approach to fusion energy generation.

Fusion, of course, is the long-awaited clean, safe theoretical solution to humanity's energy needs. It's how the Sun itself makes the vast amounts of energy that have powered life on our planet up until now. Where nuclear fission – the splitting of atoms to release energy – has proven incredibly powerful but insanely destructive when things go wrong, fusion promises reliable, safe, low cost, green energy generation with no chance of radioactive meltdown.

It's just always been 20 years away from being 20 years away. A number of multi-billion dollar projects are pushing slowly forward, from the Max Planck Institute's insanely complex Wendelstein 7-X stellerator to the 35-nation ITER Tokamak project, and most rely on a deuterium-tritium thermonuclear fusion approach that requires the creation of ludicrously hot temperatures, much hotter than the surface of the Sun, at up to 15 million degrees Celsius (27 million degrees Fahrenheit). This is where HB11's tech takes a sharp left turn.

The results of decades of research by Emeritus Professor Heinrich Hora, HB11's approach to fusion does away with rare, radioactive and difficult fuels like tritium altogether – as well as those incredibly high temperatures. Instead, it uses plentiful hydrogen and boron B-11, employing the precise application of some very special lasers to start the fusion reaction.

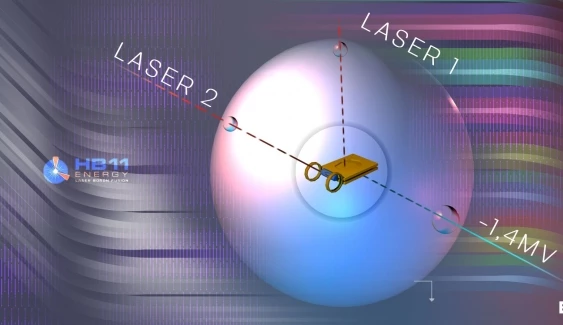

Here's how HB11 describes its "deceptively simple" approach: the design is "a largely empty metal sphere, where a modestly sized HB11 fuel pellet is held in the center, with apertures on different sides for the two lasers. One laser establishes the magnetic containment field for the plasma and the second laser triggers the ‘avalanche’ fusion chain reaction. The alpha particles generated by the reaction would create an electrical flow that can be channeled almost directly into an existing power grid with no need for a heat exchanger or steam turbine generator."

HB11's Managing Director Dr. Warren McKenzie clarifies over the phone: "A lot of fusion experiments are using the lasers to heat things up to crazy temperatures – we're not. We're using the laser to massively accelerate the hydrogen through the boron sample using non-linear forced. You could say we're using the hydrogen as a dart, and hoping to hit a boron , and if we hit one, we can start a fusion reaction. That's the essence of it. If you've got a scientific appreciation of temperature, it's essentially the speed of atoms moving around. Creating fusion using temperature is essentially randomly moving atoms around, and hoping they'll hit one another, our approach is much more precise."

"The hydrogen/boron fusion creates a couple of helium atoms," he continues. "They're naked heliums, they don't have electrons, so they have a positive charge. We just have to collect that charge. Essentially, the lack of electrons is a product of the reaction and it directly creates the current."

The lasers themselves rely upon cutting-edge "Chirped Pulse Amplification" technology, the development of which won its inventors the 2018 Nobel prize in Physics. Much smaller and simpler than any of the high-temperature fusion generators, HB11 says its generators would be compact, clean and safe enough to build in urban environments. There's no nuclear waste involved, no superheated steam, and no chance of a meltdown.

"This is brand new," Professor Hora tells us. "10-petawatt power laser pulses. It's been shown that you can create fusion conditions without hundreds of millions of degrees. This is completely new knowledge. I've been working on how to accomplish this for more than 40 years. It's a unique result. Now we have to convince the fusion people – it works better than the present day hundred million degree thermal equilibrium generators. We have something new at hand to make a drastic change in the whole situation. A substitute for carbon as our energy source. A radical new situation and a new hope for energy and the climate."

Indeed, says Hora, experiments and simulations on the laser-triggered chain reaction are returning reaction rates a billion times higher than predicted. This cascading avalanche of reactions is an essential step toward the ultimate goal: reaping far more energy from the reaction than you put in. The extraordinary early results lead HB11 to believe the company "stands a high chance of reaching the goal of net energy gain well ahead of other groups."

“As we aren’t trying to heat fuels to impossibly high temperatures, we are sidestepping all of the scientific challenges that have held fusion energy back for more than half a century,” says Dr McKenzie. “This means our development roadmap will be much faster and cheaper than any other fusion approach. You know what's amazing? Heinrich is in his eighties. He called this in the 1970s, he said this would be possible. It's only possible now because these brand new lasers are capable of doing it. That, in my mind, is awesome."

Dr McKenzie won't however, be drawn on how long it'll be before the hydrogen-boron reactor is a commercial reality. "The timeline question is a tricky one," he says. "I don't want to be a laughing stock by promising we can deliver something in 10 years, and then not getting there. First step is setting up camp as a company and getting started. First milestone is demonstrating the reactions, which should be easy. Second milestone is getting enough reactions to demonstrate an energy gain by counting the amount of helium that comes out of a fuel pellet when we have those two lasers working together. That'll give us all the science we need to engineer a reactor. So the third milestone is bringing that all together and demonstrating a reactor concept that works."

This is big-time stuff. Should cheap, clean, safe fusion energy really be achieved, it would be an extraordinary leap forward for humanity and a huge part of the answer for our future energy needs. And should it be achieved without insanely hot temperatures being involved, people would be even more comfortable having it close to their homes. We'll be keeping an eye on these guys.

Source: University of New South Wales