"We can feed black soldier flies straight, dirty trash," says a team that's working to turn insects into landfill-clearing biomanufacturing machines that turn regular, dangerous or contaminated garbage into a range of high-value products.

Black soldier flies are neither disease vectors nor pests, and they're proving increasingly useful to humans in processing waste. For many years, it's been known that their larvae have a huge appetite for organic waste like household food scraps, and a tendency to poop out highly nutritious fertilizer – and once they reach a certain size, they can be scooped up, washed, dried out and ground up into a fine powder that can be mixed in with animal feed as a source of protein and fat.

It's a bit of a grim life, but then this organic waste would normally be eaten by microbes in a landfill somewhere, which would decompose it into methane, a massively more effective greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

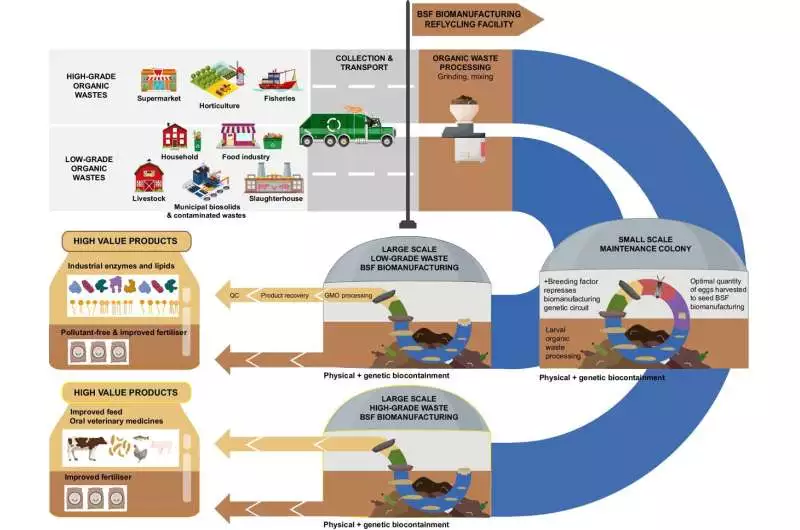

Now, synthetic biology specialists at Macquarie University propose that with a little genetic engineering, black soldier flies could be used as sustainable biomanufacturing plants, expanding their diet to include lower-grade "municipal biosolids" from sewage treatment plants and slaughterhouse waste – and tuning their output to include a range of higher-value substances.

"Insects will be the next frontier for synthetic biology applications," says Dr Maciej Maselko, senior author on a new study, "dealing with some of the huge waste-management challenges we haven't been able to solve with microbes. We can feed black soldier flies straight, dirty trash rather than sterilized or thoroughly pre-processed. When it is just chopped into smaller pieces, black soldier flies will consume large volumes of waste a lot faster than microbes."

The flies, according to the team, could be genetically altered to make them produce a range of high-value chemicals, including industrial enzymes for the livestock, textile, food and pharmaceutical industries, or specialized lipids that could replace fossil fuel oils in biofuels and lubricants. They could also be tuned to create "enhanced animal feeds" with improved nutrient ratios.

"Even the fly-poo, called 'frass,' could be enhanced to improve fertilizer," says lead author and synthetic biologist Dr. Kate Tepper. "The flies could be engineered to clean up chemical contaminants in their frass, which can be applied as pollutant free fertilizer to grow crops and prevent contaminants entering our food supply chains."

Things get even more interesting when we learn that the flies could be engineered to chow down on certain toxic wastes, and other chemical contaminants, like heavy metals and PFAS "forever plastics." The researchers believe the flies could be altered to process certain contaminants into harmless frass – or to "hyperaccumulate" others in their bodies. In either of these ways, contaminated soil and waste could be "bioremediated" by soldier fly treatment.

So it seems there's a pathway here toward greenhouse gas reductions, while breaking down several human waste streams and potentially decontaminating things as well – while also possibly producing useful products at the same time. And that last part is definitely key.

"If we want a sustainable circular economy, the economics of that have to work," says Dr. Tepper. "When there is an economic incentive to implement sustainable technologies, such as engineering insects to get more value from waste products, that will help to drive this transition more rapidly."

The Macquarie University team has already spun out a company – Entozyme – through which to commercialize its engineered insect biomanufacturing technologies.

It's certainly a fascinating idea, with all sorts of potential in a range of different applications. We look forward to learning how things work out, and where this kind of tech proves most valuable.

The research is open access in the journal Nature Communications Biology.

Source: Macquarie University via Phys.org