Researchers have created a floating, solar-powered device that converts contaminated water or seawater into clean hydrogen fuel and drinking water. Because it works with any open water source and doesn’t require external power, the device could be used in resource-limited or remote places.

Photocatalytic water splitting converts sunlight directly into storable hydrogen but often requires pure water and land for plant installation, while generating unusable waste heat. With water being a precious resource, a photocatalytic device that uses any untreated water source, such as a river, sea, water reservoir or industrial waste water, would be a more sustainable option.

So researchers from the University of Cambridge, inspired by the process of photosynthesis, created a solar-powered device capable of producing clean hydrogen fuel and clean drinking water simultaneously from polluted water or seawater.

“Bringing together solar fuels production and water production in a single device is tricky,” said Chanon Pornrungroj, the study’s lead author. “Solar-driven water splitting, where water molecules are broken down into hydrogen and oxygen, need to start with totally pure water because any contaminants can poison the catalyst or cause unwanted chemical side-reactions.”

The researchers wanted to mimic a plant’s ability to photosynthesize, but unlike previous devices that produced green hydrogen fuel from clean water sources, they wanted their device to use contaminated water, making it usable in regions where clean water is hard to find.

“In remote or developing regions, where clean water is relatively scarce and the infrastructure necessary for water purification is not readily available, water splitting is extremely difficult,” said Ariffin Mohamad Annuar, a study co-author. “A device that could work using contaminated water could solve two problems at once: it could split water to make clean fuel, and it could make clean drinking water.”

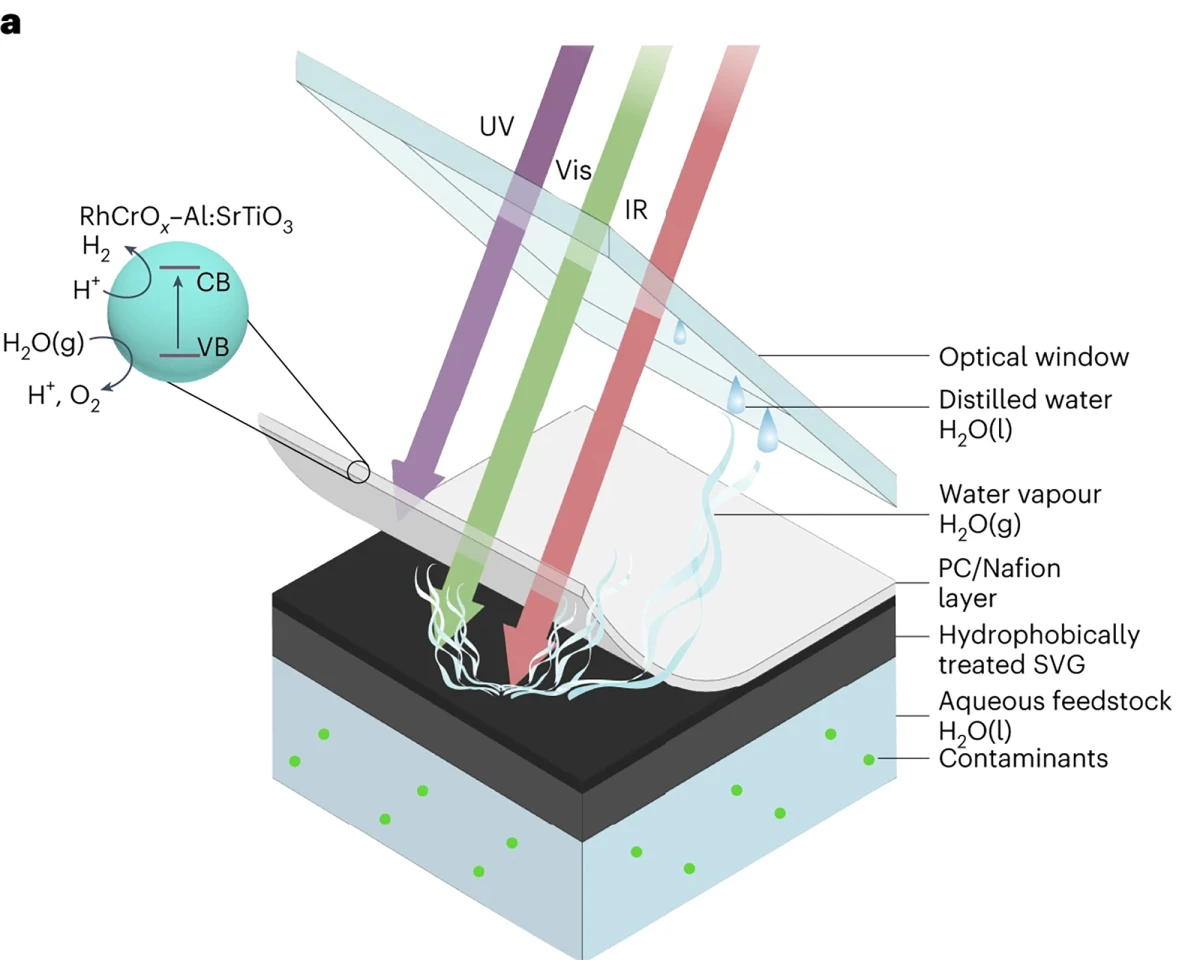

They deposited a UV-light-absorbing photocatalyst on an infrared-light-absorbing nanostructured carbon mesh, a good absorber of both light and heat, to generate the water vapor used by the photocatalyst to create hydrogen. The porous carbon mesh, treated to repel water, helped the photocatalyst float and kept it away from the water below so contaminants didn’t interfere with its functionality. In addition, this configuration allows the device to use more of the Sun’s energy.

“The light-driven process for making solar fuels only uses a small portion of the solar spectrum – there’s a whole lot of the spectrum that goes unused,” Annuar said.

So, the researchers used a white, UV-absorbing layer on top of the floating device for hydrogen production via water splitting. The rest of the light in the solar spectrum is transmitted to the bottom of the device, which vaporizes the water. This, say the researchers, more closely mimics transpiration, the process of water movement through a plant and its evaporation from aerial parts such as leaves, stems and flowers.

“This way, we’re making better use of the light – we get the vapor for hydrogen production, and the rest is water vapor,” said Pornrungroj. “This way, we’re truly mimicking a real leaf since we’ve now been able to incorporate the process of transpiration.”

The researchers tested their device using real-world open water sources, including water from the River Cam in central Cambridge and turbid industrial waste from the paper industry. In artificial seawater, the device retained 80% of its initial performance after 154 hours. The researchers say that because the photocatalyst is isolated from contaminants in the water source and remains relatively dry, the device can maintain its operational stability.

“It’s so tolerant of pollutants, and the floating design allows the substrate to work in very cloudy or muddy water,” said Pornrungroj. “It’s a highly versatile system.”

The researchers say their device has the potential to address issues of sustainability and the circular economy.

“Our device is still a proof of principle, but these are the sorts of solutions we will need if we’re going to develop a truly circular economy and sustainable future,” said Erwin Reisner, corresponding author of the study. “The climate crisis and issues around pollution and health are closely related, and developing an approach that could help address both would be a game-changer for so many people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Water.

Source: University of Cambridge