Microplastics are increasingly found to be polluting oceans and waterways and causing unknown damage to the health of animals and humans. Now, a new study provides evidence there's cross over with another looming public health threat – antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

Even as we get better at cutting back on single-use plastics and recycling those we do use, countless tiny particles of the stuff make their way into the environment. Microplastic particles have been found all over the globe – from Arctic snowfall to Antarctic sea ice, and from the bottom of deep ocean trenches to the top of Mt. Everest.

Growing evidence shows that these microplastics travel up the food chain, from insects and plankton into birds, fish, seals, turtles – and humans. Exactly what damage they might be doing once they gets into our bodies is still being investigated.

A new study has now found another health problem they potentially contribute to. Microplastic particles in urban wastewater treatment plants seem to make perfect “marketplaces” for superbugs to grow and exchange drug-resistance genes.

“A number of recent studies have focused on the negative impacts that millions of tons of microplastic waste a year is having on our freshwater and ocean environments, but until now the role of microplastics in our towns’ and cities’ wastewater treatment processes has largely been unknown,” says Mengyan Li, corresponding author of the study. “These wastewater treatment plants can be hotspots where various chemicals, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pathogens converge and what our study shows is that microplastics can serve as their carriers, posing imminent risks to aquatic biota and human health if they bypass the water treatment process.”

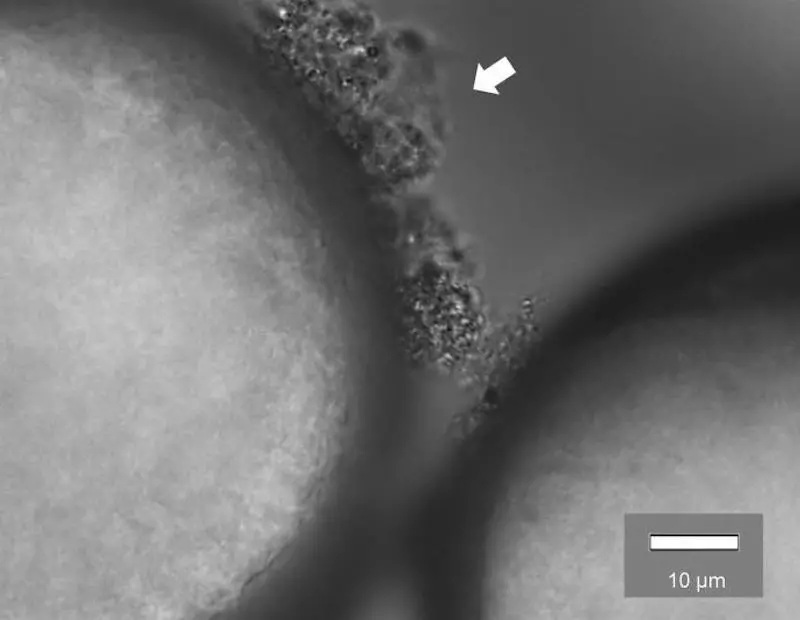

The root of the problem, the team says, is that these microplastics provide a relatively large surface area for the superbugs to cling to. When they do, they can form sticky biofilms that protect them from harm, and allow them to share genes that bestow drug resistance.

To test this, the researchers collected samples from three wastewater treatment plants in New Jersey, and introduced two types of microplastics – polyethylene and polystyrene – into some of them, while sand was added to other samples as a control. Then they tracked which species of bacteria grew on each, as well as their genetic changes.

Eight species of bacteria were found to cling to the microplastics in much higher number than in the sand samples. After just three days, the team found that three specific genes called sul1, sul2 and intl1, which confer antibiotic resistance, were present at concentrations of up to 30 times higher in the microplastic samples than the sand ones. Adding extra antibiotics to the samples boosted the number of these resistance genes by 4.5 times.

“Previously, we thought the presence of antibiotics would be necessary to enhance antibiotic-resistance genes in these microplastic-associated bacteria, but it seems microplastics can naturally allow for uptake of these resistance genes on their own.” says Dung Ngoc Pham, first author of the study. “The presence of antibiotics does have a significant multiplier effect however.”

Previous studies have shown that biofilms forming around microplastic particles helps them be taken up by biological tissues more easily. Now it looks like they’re also contributing to a completely different public health concern – our best drugs are becoming less and less effective over time, which may eventually cast us back to a time before antibiotics when basic infections were much more life-threatening.

The team says they plan to continue investigating the issue, specifically whether these superbug-loaded microplastics are making their way into the environment. To do so, the next steps involve exposing them to wastewater treatment processes like UV and chlorine to see if the biofilms protect the bacteria. We may need to come up with new ways to remove microplastics during the water treatment process.

The research was published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters.