A newly published article in the prestigious journal The Lancet is offering the most thorough insights to date into the clinical characteristics of the rapidly spreading novel coronavirus. The study examined 99 of the earliest cases detected, describing the most common symptoms and the types of patients most likely to contract the virus.

Following a wave of unexplained cases of viral pneumonia in the Chinese city of Wuhan across December 2019, a novel coronavirus was detected. Labeled 2019-nCoV, the spread of the virus has been swift. As of January 29, 2020, it has spread to 20 countries with over 6,000 confirmed cases and 133 deaths.

Scientists have been working hard to understand the characteristics of this new virus. While it belongs to the same general family of viruses responsible for the SARS and MERS outbreaks, its unique properties are still unclear. A new Lancet study is presenting the most comprehensive clinical description of the virus published so far, encompassing 99 patients admitted with the virus to a local Wuhan hospital.

The study revealed the average age of infected patients was 55, and the majority (68 percent) were male. Half of the patients studied were suffering from a pre-existing chronic disease and 49 percent had a direct connection to the food market suspected to be the origin of the virus.

Symptomatically, most patients displayed fever and/or cough on admission to hospital. These are the two most prominent and consistent symptoms seen in the virus. Other symptoms seen in some patients included shortness of breath, muscle aches and headaches.

Commenting on an earlier investigation into the clinical characteristics of this new virus, Paul Hunter from the University of East Anglia noted there are key symptomatic differences between this coronavirus and its notorious counterpart, SARS.

“What comes through strongly is that the clinical features and epidemiology of the recent outbreak is very similar to SARS with one big difference – the relative lack of upper respiratory tract symptoms such as runny nose, sore throat and sneezing compared to what was seen in SARS,” says Hunter. “This is very important as sneezes and runny noses are a prime way for people to spread infection.”

By the endpoint of the study, January 25, only 11 patients had died from the virus, while 31 had recovered and been discharged. The scientists behind this new analysis suggest most of the deceased patients were older than 60 years with pre-existing medical conditions. Those patients with the virus that did die primarily did so from acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, a critical form of respiratory failure.

While the mortality rate in this studied cohort is around 11 percent, the scientists say some patients currently hospitalized may still succumb to the virus. However, it is also noted that this high mortality rate only accounts for acute hospitalized cases and is not indicative of the virus’s general virulence in the real world.

One of the more compelling data points raised in the study is the virus’s tendency to be of a higher infection risk to men rather than women. This resembles one of the stranger traits seen in the earlier SARS and MERS outbreaks.

“The reduced susceptibility of females to viral infections could be attributed to the protection from X chromosome and sex hormones, which play an important role in innate and adaptive immunity,” the scientists hypothesize in the new study.

The ultimate takeaway from this analysis, the scientists claim, is that older males with pre-existing chronic diseases are most at risk from the novel coronavirus.

The outbreak is, of course, still a dynamic and fast-moving global emergency with a variety of questions still unanswered. Particularly unclear is exactly how contagious the virus may be, and whether it is transmissible when a carrier is still asymptomatic.

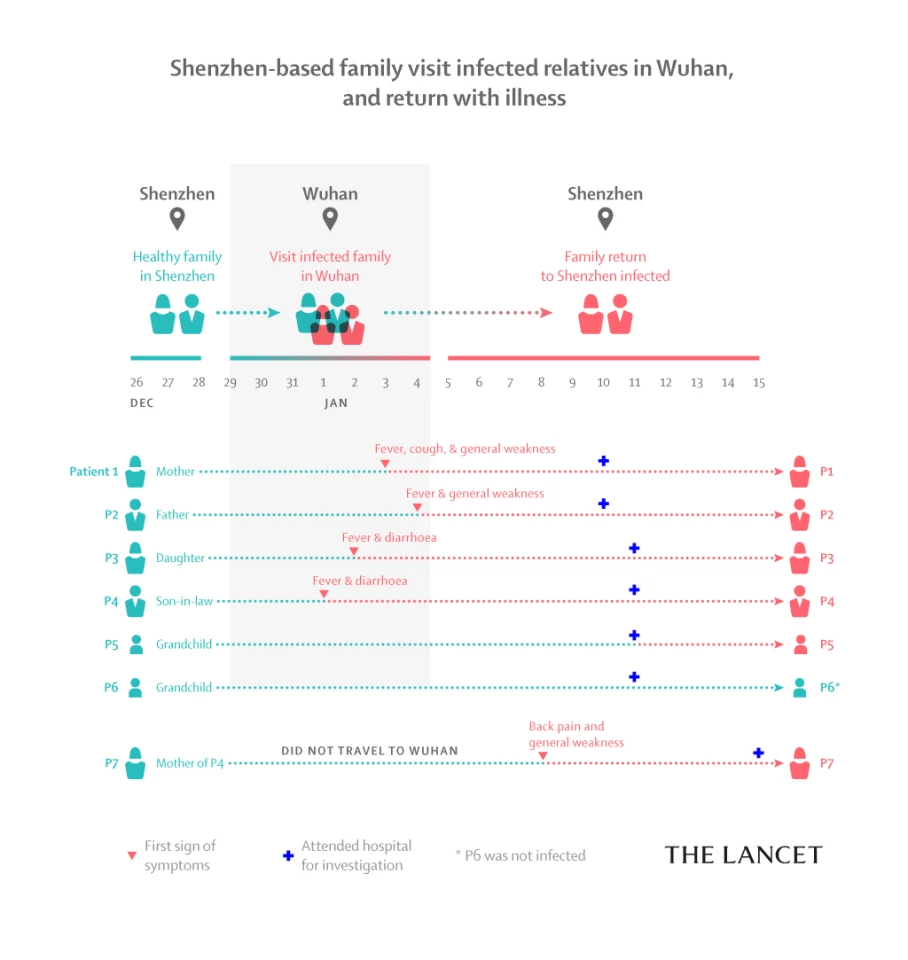

Another recently published case study in The Lancet describes how the virus infected a whole family in early January. As well as verifying person-to-person transmission, the case study suggests asymptomatic transmission of the virus is possible. One 10-year-old child in the family was diagnosed with the virus while curiously remaining completely without symptoms. While asymptomatic cases of SARS were detected in the past, they were very rare.

“Because asymptomatic infection appears possible, controlling the epidemic will also rely on isolating patients, tracing and quarantining contacts as early as possible, educating the public on both food and personal hygiene, and ensuring health care workers comply with infection control,” said Kwok-Yung Yuen, lead researcher on the family case study.

The new coronavirus clinical study was published in The Lancet.