As the world grapples with ways to safely come out of social lockdowns without triggering new viral outbreaks, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) continues to publish compellingly detailed case studies investigating COVID-19 clusters. These case studies offer granular insights into what are often referred to as super-spreader events.

Around one in five people are traditionally thought to be super-spreaders. These are people who seem to transmit a given infectious disease significantly more widely than most.

There are a variety of hypotheses trying to explain super-spreading events, from environmental factors putting someone in a place where it is easy to spread the virus widely (someone in food service, for example), to the possibility some people seem to actively shed very high volumes of virus particles while barely exhibiting any symptoms.

The novel coronavirus, named SARS-CoV-2, is now known to be highly infectious and although major lockdowns or stay-at-home orders can limit person-to-person transmission, the world obviously cannot remain in social quarantine for years waiting for a vaccine to be developed. As towns and cities across the globe begin to reopen, a huge question remains unanswered.

What spaces and services can safely reopen without triggering new outbreaks?

One way to grapple with this question is through examining several of the CDC’s detailed investigations into clusters of cases over the past couple of months. This trio of detailed super-spreading events offers insights into how easily single gatherings can trigger deadly chains of transmission.

Choir practice, extended family gatherings, and small church events all present significant challenges for authorities trying to reopen their communities. And understanding how these super-spreading events kick off in the first place may be the best path to preventing them in the future, helping us get back to some kind of normalcy.

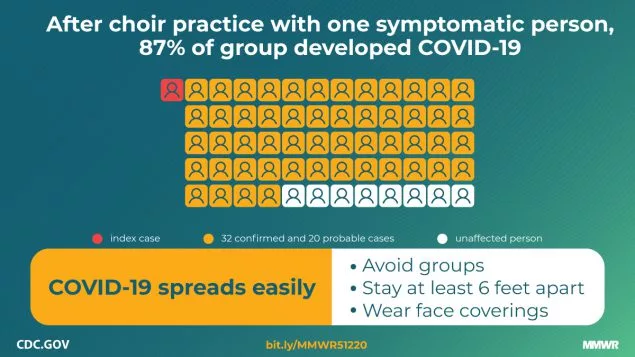

One choir practice, 53 cases, two deaths

On Tuesday March the 10th, in Skagit County, Washington, a group of choir members met for their weekly rehearsal. At that point in time news of the novel coronavirus had already been spreading, and after some consideration, it was decided the rehearsal would continue as scheduled, albeit with some cursory protections.

From around 6 pm members of the choir began to arrive. They were offered hand sanitizer on entry, and physical contact was limited, with no handshakes or hugs reportedly taking place across the two-and-a-half-hour event. All up, 61 singers took part in the rehearsal.

Over 120 chairs were set up in a large multipurpose space, and since only half of the choir was present, there were many empty spaces between singers. In between two 40-minute group rehearsals, the singers split into two smaller groups for a 50-minute practice.

A 15-minute break took place before the final session. Cookies and oranges were freely available from a table at the back of the main space, but many members refrained from eating the snacks.

“Most attendees left the practice immediately after it concluded. No one reported physical contact between attendees,” the CDC report states.

Within two weeks, 87 percent of those at the March 10 rehearsal were confirmed to have contracted COVID-19. Two of the 53 infected subjects died.

Although a small number of attendees began displaying COVID-19 symptoms within two days of the March 10 practice, suggesting they may have been infected earlier, the CDC investigators suspect the vast majority of cases could be tracked back to this single super-spreading event.

Alongside the potential of several subjects infecting others during their pre-symptomatic period, the report found one individual did attend the rehearsal with active cold-like symptoms. They had been exhibiting symptoms for three days, and subsequent testing confirmed COVID-19.

Exactly how each individual contracted the virus over the course of this two-and-half-hour choir rehearsal is still unknown. While the virus is still primarily thought to be transmitted by direct touch, not all cases in this particular event can be explained that way. The CDC report does recognize actions such as stacking chairs and sharing snacks may account for some of the infections, but the big mystery in this scenario surrounds the act of singing, and how that may have potentiated the super-spreading event.

“The act of singing, itself, might have contributed to transmission through emission of aerosols, which is affected by loudness of vocalization,” the CDC report states. “Certain persons, known as super-emitters, who release more aerosol particles during speech than do their peers, might have contributed to this and previously reported COVID-19 super-spreading events.”

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, UCLA infectious disease expert Jamie Lloyd-Smith hypothesized the act of singing could reasonably disperse viral particles much more widely than general breathing and talking.

“One could imagine that really trying to project your voice would also project more droplets and aerosols,” said Lloyd-Smith.

The extended family gatherings

In late February a Chicago man experiencing mild respiratory symptoms was linked to 16 confirmed COVID-19 cases, resulting in three deaths. The infections were thought to have occurred over a three-day period spanning several family gatherings, including a funeral and a birthday party.

The cluster began when the man shared a takeout meal with two family members of the deceased, the night before the funeral. Over the course of three hours the trio talked and ate out of shared serving dishes.

The next day at the funeral the infected man shared a communal “potluck-style” meal and hugged a number of family members. Three days later the man, still mildly symptomatic, attended a family birthday party. The event took place in a family member’s home and was attended by 10 people, including the primary COVID-19 subject.

For the next three hours the group celebrated in the house, sharing food and occasionally embracing. A week later seven of the party attendees had developed COVID-19.

“Within three weeks after mild respiratory symptoms were noted in the index patient, 15 other persons were likely infected with SARS-CoV-2, including three who died,” the CDC report states. “Patient A1.1, the index patient, was apparently able to transmit infection to 10 other persons, despite having no household contacts and experiencing only mild symptoms for which medical care was not sought.”

The CDC report suggests this particular cluster strikingly highlights the important of social distancing within family units. Although extended family gatherings may feel somewhat safer than broader non-family encounters in public spaces, this case report illustrates how swiftly the virus can spread from small gatherings of people from multiple households.

The church chain

Between March 6 and March 8 a church in rural Arkansas hosted a multi-day children’s event. Over the course of the three days adults and children participated in games involving close contact, and a buffet-style shared meal.

On March 11 the church’s pastor and his wife began to develop a mild cough and fever. The next day, upon hearing about similar respiratory symptoms appearing in the congregation, the pastor immediately closed his church. Testing revealed the pair had indeed contracted COVID-19, and investigations tracked the exposure back to the church events a few days prior.

The investigation homed in on the source as two subjects who attended the church events between March 6 and 8 while they were mildly symptomatic. From the multi-day children’s event, to an additional bible study class at the church on March 11, there were 35 subsequent COVID-19 cases directly linked to the gatherings.

Out of the 92 attendees linked to church events over that five-day period, 38 percent were confirmed with COVID-19 and three ultimately died. The CDC report suggests an additional 26 cases of community transmission could be linked back to this chain, all stemming from two symptomatic individuals attending a few church events.

“Despite canceling in-person church activities and closing the church as soon as it was recognized that several members of the congregation had become ill, widespread transmission within church A and within the surrounding community occurred,” the CDC report states. “The primary patients had no known COVID-19 exposures in the 14 days preceding their symptom onset dates, suggesting that local transmission was occurring before case detection.”

Irwin Redlener, director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness, says this case study illustrates the concerning way the virus can spread so easily via religious gathering spaces. Speaking to the The Daily Beast, Redlener suggests this particular case may be less an example of a more contagious “super-spreader” and more an indication of how church gatherings in particularly can trigger clusters of infection.

“People can go to church and become infected and then spread it into their larger communities, and with an infection like SARS-CoV-2, this could really promote a major secondary or tertiary wave of infection in the larger community,” said Redlener. “It’s not just limited to the people who attend these services.”

These three case studies offer clues as to what kinds of social interactions may need the most vigilance moving forward. There are volumes of similar case studies appearing, offering insights into how clusters can stem from nightclubs, bars, schools, and cinemas.

Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization's emergency health program, recently said it is unlikely this virus is going away anytime soon. Ryan noted, even with a vaccine, it is possible this virus could become endemic. So, the sooner we can adapt our social environments to limit its transmission, the sooner we can get back to some kind of normalcy.