Our health is guided not only by our genetic blueprint but also by our lifestyle choices and environmental exposures. The study of epigenetics involves looking at what particular markers regulate gene expression.

Just because someone may have a genetic predisposition to a certain illness, for example, doesn't mean they will necessarily get sick. The expression of certain genes can be turned up or down via an assortment of factors, and scientists have known for a number of years that exercise in particular can trigger a variety of beneficial epigenetic changes in the human body.

One fascinating study back in 2014 homed in on the way exercise affects gene expression by tasking a small cohort of volunteers to perform a one-legged cycling task for three months. At the end of the study period the researchers saw changes in about 4,000 genes when studying skeletal muscle from the exercised leg compared to the untrained leg.

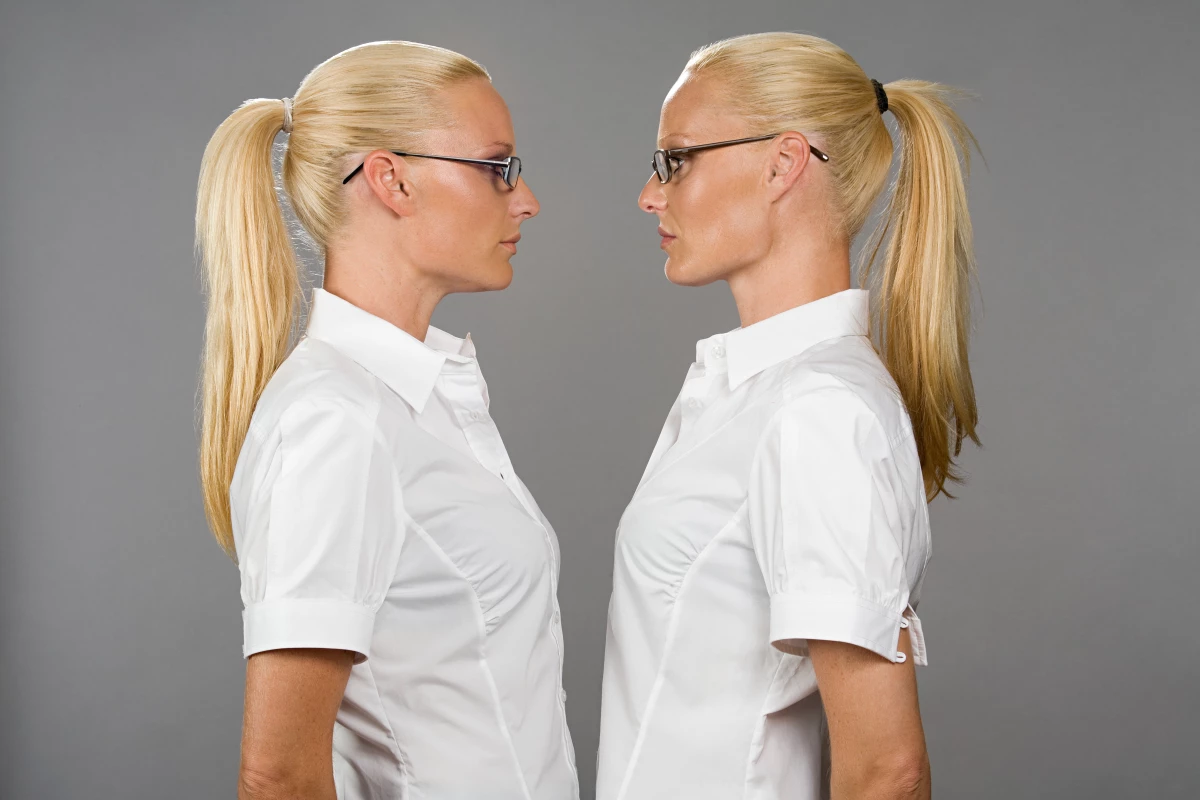

But a new study from researchers at Washington State University explored the epigenetics of exercise in a novel way, looking at gene expression differences in identical twins.

“If genetics and DNA sequence were the only driver for biology, then essentially twins should have the same diseases," said Michael Skinner, corresponding author on the new study. "But they don't. So that means there has to be an environmental impact on the twins that is driving the development of disease.”

The researchers recruited 70 pairs of identical twins. Alongside measuring their body-mass index and surveying their exercise habits, each participant wore a fitness tracker for one week to objectively ascertain their physical activity levels.

A twin pair was determined to be "discordant" if one twin completed more than 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity a week while the other twin performed less than 150 minutes in a week. Around 40 percent of the twin pairs were found discordant on this measure.

Looking at the epigenetic variances between these physically discordant identical twin pairs, the researchers found markers on over 50 genes. The exercise-induced gene expression changes were found in genes previously associated with a lower risk of metabolic syndrome.

“The findings provide a molecular mechanism for the link between physical activity and metabolic disease,” said Skinner. “Physical exercise is known to reduce the susceptibility to obesity, but now it looks like exercise through epigenetics is affecting a lot of cell types, many of them involved in metabolic disease.”

While this study isn't the first to home in on the epigenetic effects of exercise, it certainly offers novel insights by focusing on the differences between genetically identical twins. As well as adding to our increasing body of knowledge on the physiological ways exercise improves our health, the findings are a potent reminder that our genes are not necessarily our destiny.

The new study was published in Scientific Reports.

Source: Washington State University