A new study has found a link between the bacteria responsible for gum disease and atrial fibrillation, a common heart rhythm disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. It emphasizes the importance of adopting a holistic approach to medicine.

In much the same way as knowledge of the benefits of a healthy gut microbiome has expanded exponentially, more and more research has begun demonstrating a connection between mouth health and disease. New Atlas has previously covered research linking oral bacteria with Alzheimer’s disease, gut inflammation, and heart disease.

Now, a new study led by Hiroshima University (HU) in Japan has found a link between the bacterium responsible for gum disease, or periodontitis, and the common heart rhythm disorder atrial fibrillation (AFib).

“The causal relationship between periodontitis and atrial fibrillation is still unknown, but the spread of periodontal bacteria through the bloodstream may connect these conditions,” said the study’s lead author, Shunsuke Miyauchi, MD, an assistant professor at HU’s Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences.

The most common clinically significant heart rhythm disorder, the global prevalence of AFib – also called AF – is high and continues to rise. The condition is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, stroke, and death. Periodontitis is the name given to a group of inflammatory oral infections caused by bacteria that live on tooth surfaces and destroy underlying supporting tissues. The condition can range from mild gingivitis (gum inflammation) to the chronic destruction of dental tissue, resulting in tooth loss. Porphyromonas gingivalis is one such bacterium and was the focus of the present study.

“Among various periodontal bacteria, P. gingivalis is highly pathogenic to periodontitis and some systemic diseases outside the oral cavity,” Miyauchi said. “In this study, we have addressed these two questions: Does P. gingivalis translocate to the left atrium from the periodontitis lesion? And, if so, does it induce the progression of atrial fibrosis and AFib?”

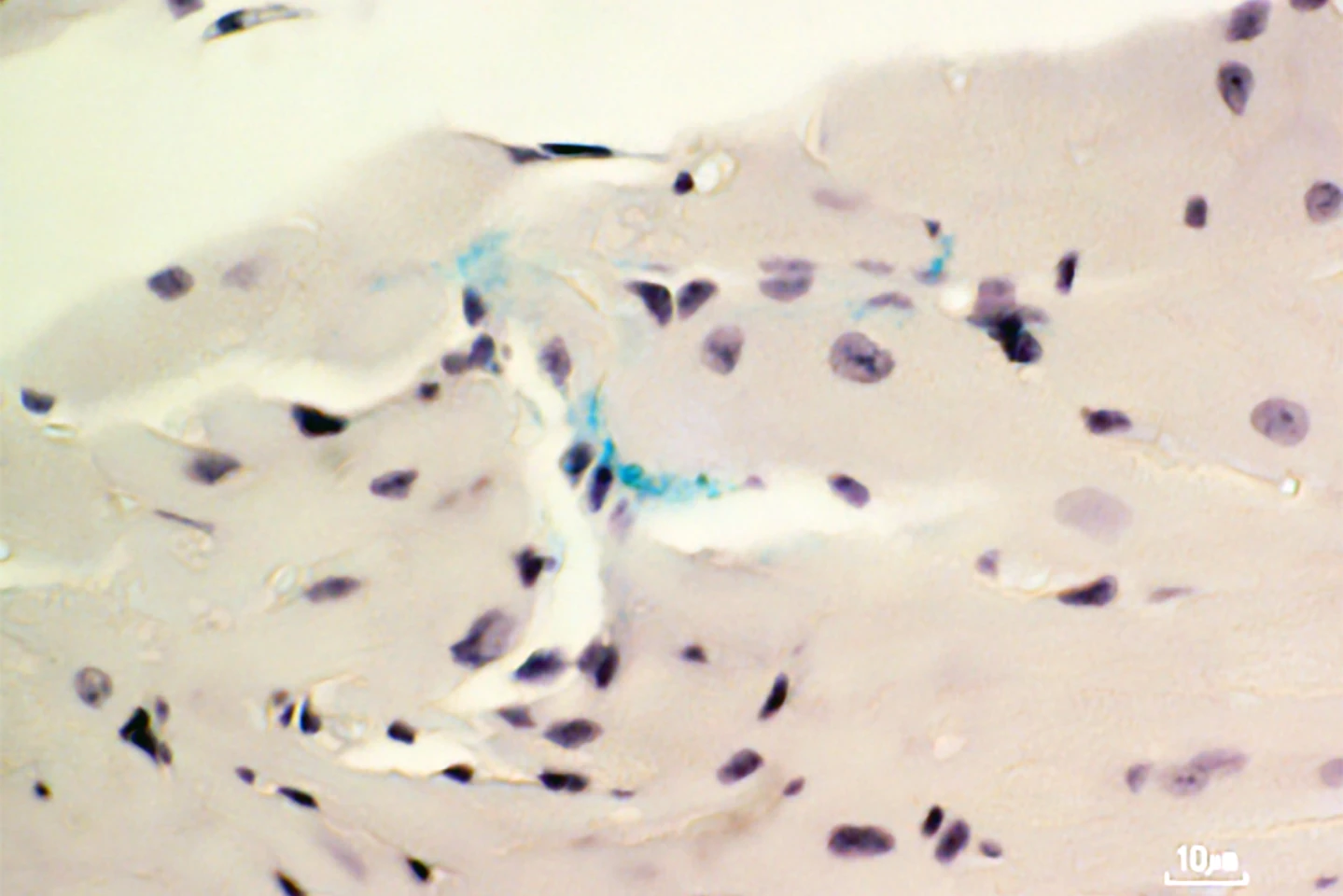

Using mice infected with P. gingivalis, the researchers confirmed the movement of the bacterium from the site of dental inflammation to the left atrium, the upper heart chamber where AFib originates, via the bloodstream. They did this by testing the DNA of the bacterium in the mouth and the heart and finding that they matched.

Additionally, P. gingivalis-infected mice showed a higher degree of scar tissue in the atrium (21.9% vs 16.3%) and a higher AFib inducibility (30% vs 5%), which is the ability to trigger an episode of AFib through controlled heart stimulation, than control mice. In a separate human study, researchers analyzed left atrial tissue from 68 patients with AFib and found P. gingivalis there, too. It was present in greater amounts in those patients with severe gum disease.

“P. gingivalis invades the circulatory system via the periodontal lesions and further translocates to the left atrium, where its bacterial load correlates with the clinical severity of periodontitis,” said Miyauchi. “Once in the atrium, it exacerbates atrial fibrosis, which results in higher AFib inducibility. Therefore, periodontal treatment, which can block the gateway of P. gingivalis translocation, may play an important role in AFib prevention and treatment.”

Translating that into plain language, Miyauchi is saying that because the severity of gum disease correlated with the amount of bacteria found in the heart’s upper chamber, a way of preventing the movement of bacteria from the mouth to the heart, and thereby reducing the risk of developing AFib, is to maintain good oral hygiene.

“For the next step, we’re investigating the specific mechanisms by which P. gingivalis affects atrial cardiomyocytes [heart muscle cells],” Miyauchi said. “We’re also now focusing on establishing a collaborative medical and dental system in Hiroshima Prefecture to treat cardiovascular diseases, including atrial fibrillation. We aim to expand this initiative nationwide in the future.”

The study was published in the journal Circulation.

Source: Hiroshima University