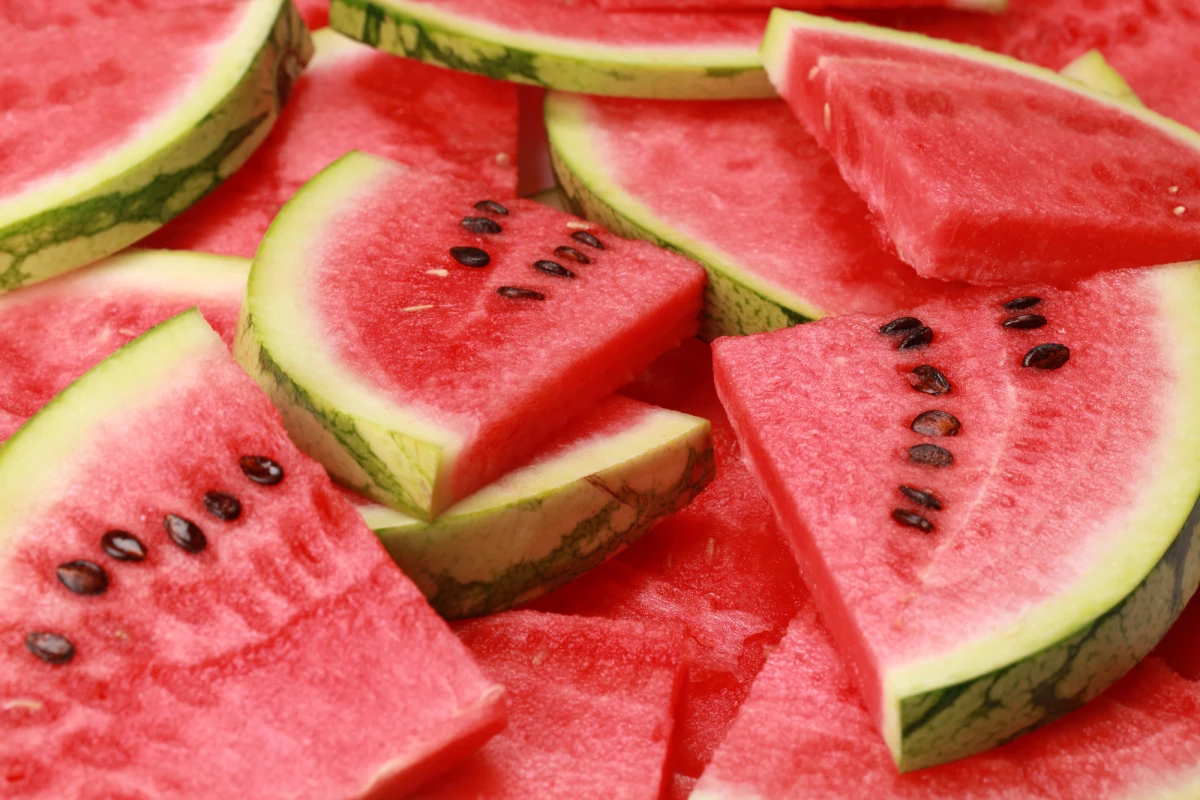

There’s nothing quite as refreshing as a slurpy bite of watermelon on a hot day. With the US watermelon season fast approaching, many are looking forward to eating the naturally sweet fruit. And because watermelon is made up of 92% water, nothing in it can cause health problems, right? Not quite.

A collection of three case studies recently published in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine has identified an under-recognized problem: watermelon contains a surprising amount of potassium. Ordinarily, this wouldn’t cause a problem, but it certainly can be for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition that affects an estimated 35.5 million US adults – about 14% of the population.

CKD refers to all conditions that affect the kidney’s ability to filter blood and remove waste. As many as 9 out of 10 people with CKD don’t know they have it because it’s most often diagnosed at more advanced stages when symptoms become more apparent.

Why is potassium important, and why is high potassium bad?

Potassium is necessary for the normal functioning of all cells. It regulates the heartbeat, ensures that muscles contract and nerves function properly, and regulates fluid levels inside the cells.

A typical blood potassium level for adults is between 3.6 and 5.2 millimoles per liter (mmol/L). A potassium level below 3.5 mmol/L is considered low (hypokalemia), and above 5.5 mmol/L high (hyperkalemia).

Before going on, here’s an interesting etymological side note: ‘Potassium’ is derived from the English word ‘potash,’ which refers to an early method of extracting potassium salts. The symbol for potassium, K, comes from the Neo-Latin word kalium, derived from the root word ‘alkali,’ which is derived from the Arabic word for ‘plant ashes,’ al qalīy.

While hypokalemia and hyperkalemia are both potentially life-threatening, the focus here is on the latter. Mild hyperkalemia is usually asymptomatic, whereas potassium levels of around 6.5 to 7 mmol/L can produce symptoms such as heart rhythm disturbances – including asystole, which is when the heart’s electrical system fails or ‘flatlines’ – muscle weakness or paralysis.

But people with long-term or chronic hyperkalemia, such as those with CKD, may not show symptoms at higher potassium levels. For them, increased potassium intake from food can raise potassium to a dangerous level.

In the cases presented in the Annals, three patients with some form of CKD developed hyperkalemia after eating large amounts of watermelon over a period ranging from three weeks to two months.

Patient 1

A 56-year-old man with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes and severe (stage 4) CKD was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after a 15-second episode of loss of consciousness or syncope. On examination, he had a dangerously low heart rate of 20 beats/minute – normal resting heart rate ranges from 60 to 100 bpm – and extremely low blood pressure: 62/32 mmHg (millimeters of mercury). Lab tests revealed a potassium level of 7 mmol/L; the man’s levels before admission to the hospital had been around 4.5 to 5 mmol/L. The high potassium was treated.

The man reported eating “large amounts” of watermelon each night for the previous two months. Doctors diagnosed hyperkalemia caused by increased dietary potassium intake in combination with his severe CKD, the blood pressure medication he was taking (lisinopril), and possibly the inability of his kidneys to remove enough potassium in the setting of long-standing diabetes. After being advised to reduce his watermelon intake, the hyperkalemia didn’t recur.

Patient 2

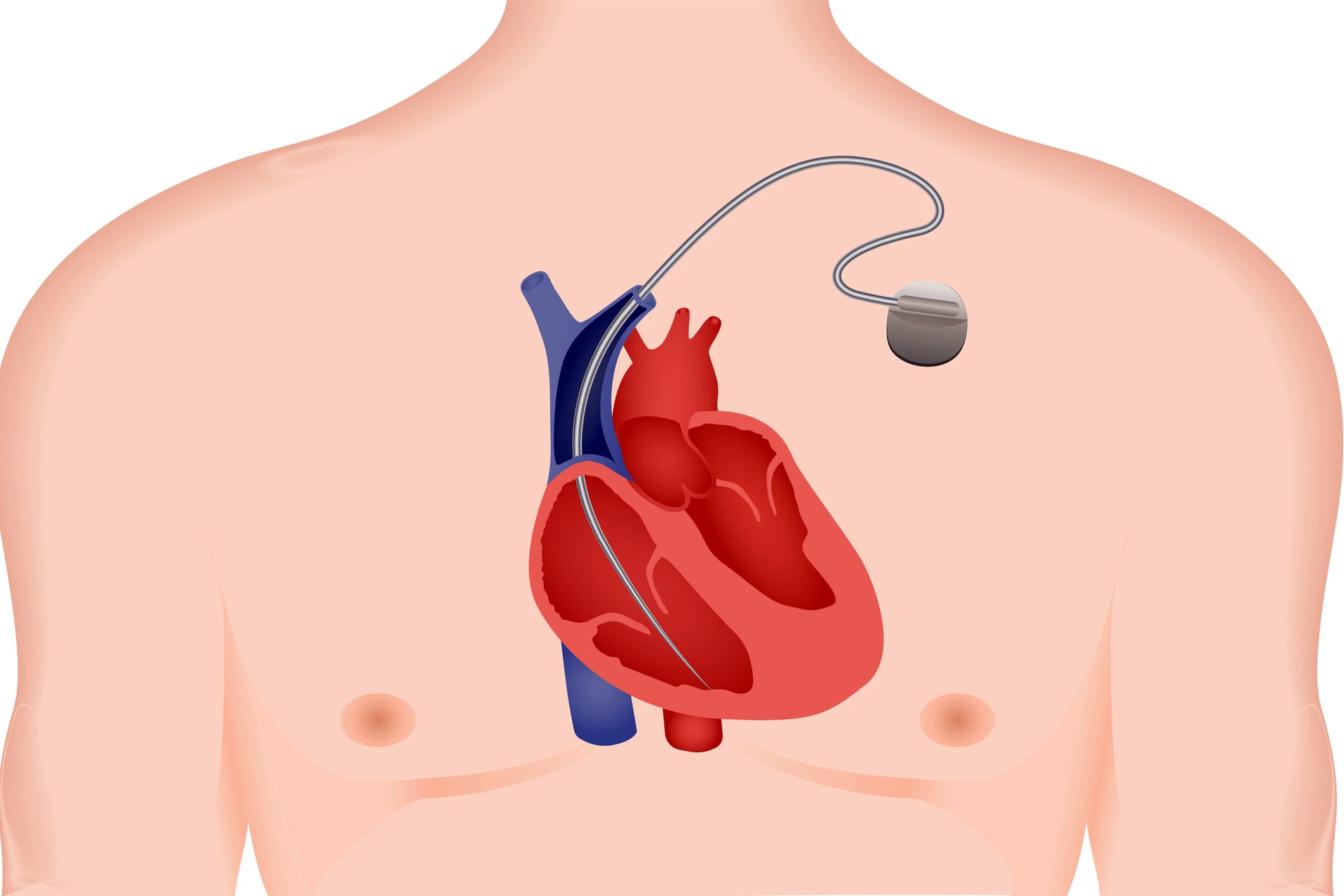

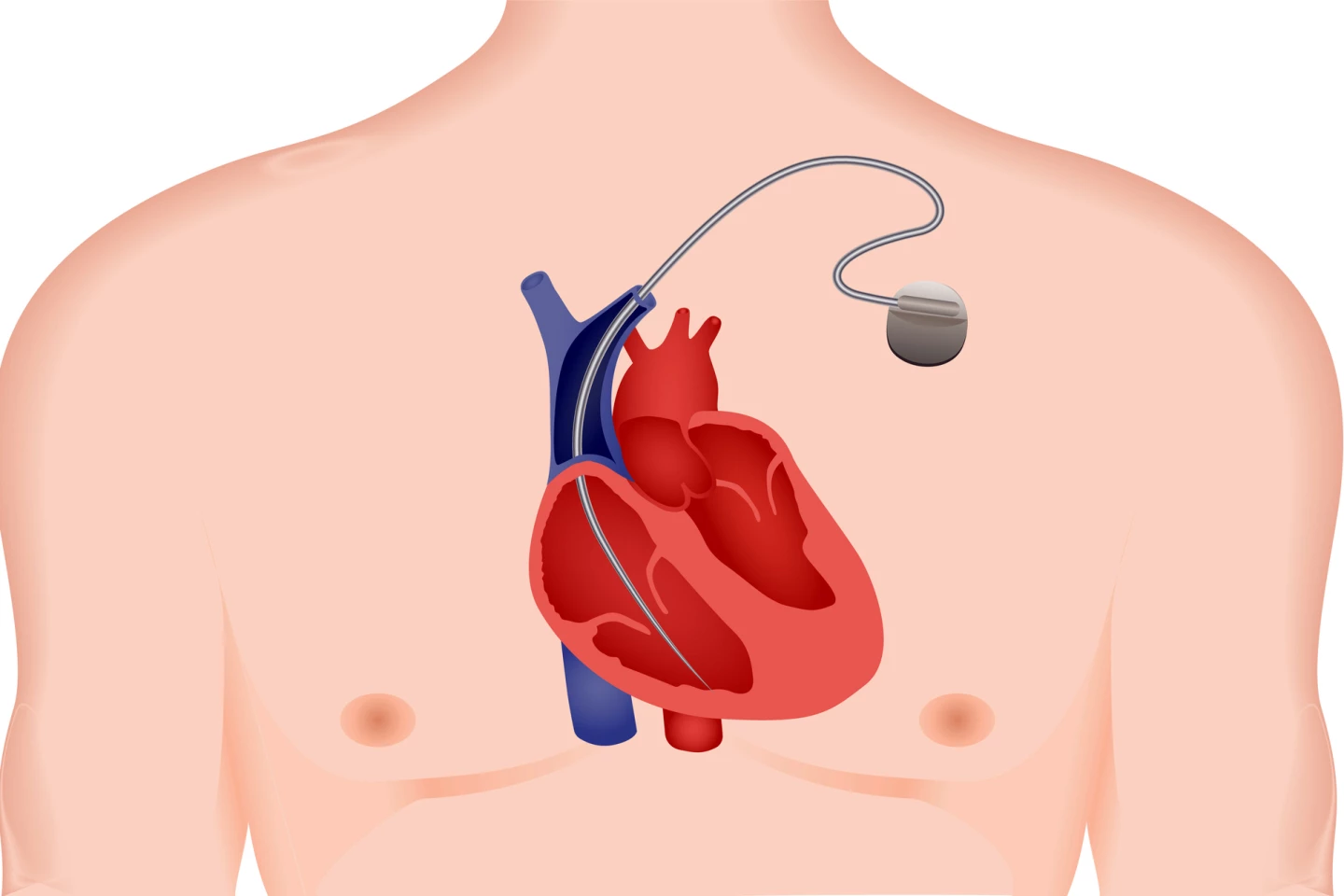

In the second case, a 72-year-old man with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy (where the heart muscle doesn’t pump well because of damage caused by a lack of blood supply) and an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) was admitted to ICU after the defibrillator had delivered an electric shock.

On presentation, his blood pressure was 176/90 mmHg, and his heart rate was regular at 66 bpm. His ECG was normal. Lab results showed a potassium level of 6.6 mmol/L. The patient was taking medication for high blood pressure (valsartan).

Information obtained from the AICD revealed that a single episode of ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF or V-Fib) had triggered the delivery of the electric shock. VT is when the bottom chambers of the heart beat very quickly. VF is when they contract rapidly in a disorganized manner; it’s a life-threatening rhythm because it prevents the heart from pumping effectively.

When a history was taken, the man disclosed that he’d been drinking two glasses of watermelon juice daily for about a month before the episode. Doctors concluded that valsartan plus high dietary potassium intake reduced the kidney’s ability to offload potassium and led to hyperkalemia, which triggered the heart arrhythmia. The man was educated on the importance of avoiding high-potassium foods, and three months later, his potassium levels were within the normal range.

Patient 3

A 36-year-old woman with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis was found to have persistent asymptomatic hyperkalemia in the course of monthly lab tests at her outpatient dialysis unit. Despite dialysis, where a machine filters waste and water from the blood because the kidneys can’t, her potassium levels rose to 7.4 mmol/L. (Previous levels had been 5 mmol/L and below.)

The woman admitted to eating “large quantities” of watermelon every day for the preceding three weeks, which was deemed to be the cause of her hyperkalemia. She backed off, and the problem didn't recur.

What do these cases tell us?

Potassium is found in fruits such as dried apricots, prunes, raisins, orange juice, and – the most well-known potassium-containing fruit – bananas. It’s also found in veggies like potatoes, spinach, tomatoes, and broccoli, milk, yogurt, meats, poultry and fish, and lentils, kidney beans, soybeans, and nuts.

Due to evidence linking potassium intake to reduced blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke in adults, in 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that adults increase their potassium intake from food to at least 90 mmol/day (3,510 mg/day).

A medium baked potato with the skin on provides 925 mg, and half an avocado provides 490 mg. An 80 g (2.8 oz) portion of salmon gives 534 mg, and the same amount of turkey gives 250 mg. Two tablespoons of peanut butter provide 210 mg. A medium banana yields 425 mg of potassium.

However, as this case series demonstrates, a high potassium load can be life-threatening for people with impaired kidney function. People know that bananas are rich in potassium but are less aware – if they’re aware at all – that watermelons are, too. A wedge of watermelon contains 320 mg of the mineral, and a 15- to 17.5-inch slice a whopping 5,060 mg, almost one-and-a-half times the recommended daily intake.

The study is available in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine.