Materials stay cooler when water evaporates off of them, but once all the water is gone, the cooling effect stops. Bearing this in mind, MIT scientists have developed a camel fur-inspired material that could keep items cool without using electricity.

Although it might initially seem like a bare-skinned camel would stay cooler overall than one covered with fur, that isn't the case. The fur acts as a gas-permeable insulating layer, shading the animal's skin from external heat while still allowing sweat to evaporate off of it. As a result, the evaporative cooling effect lasts longer – the camel still sweats, but not as much as the hypothetical bare-skinned one would before becoming dehydrated.

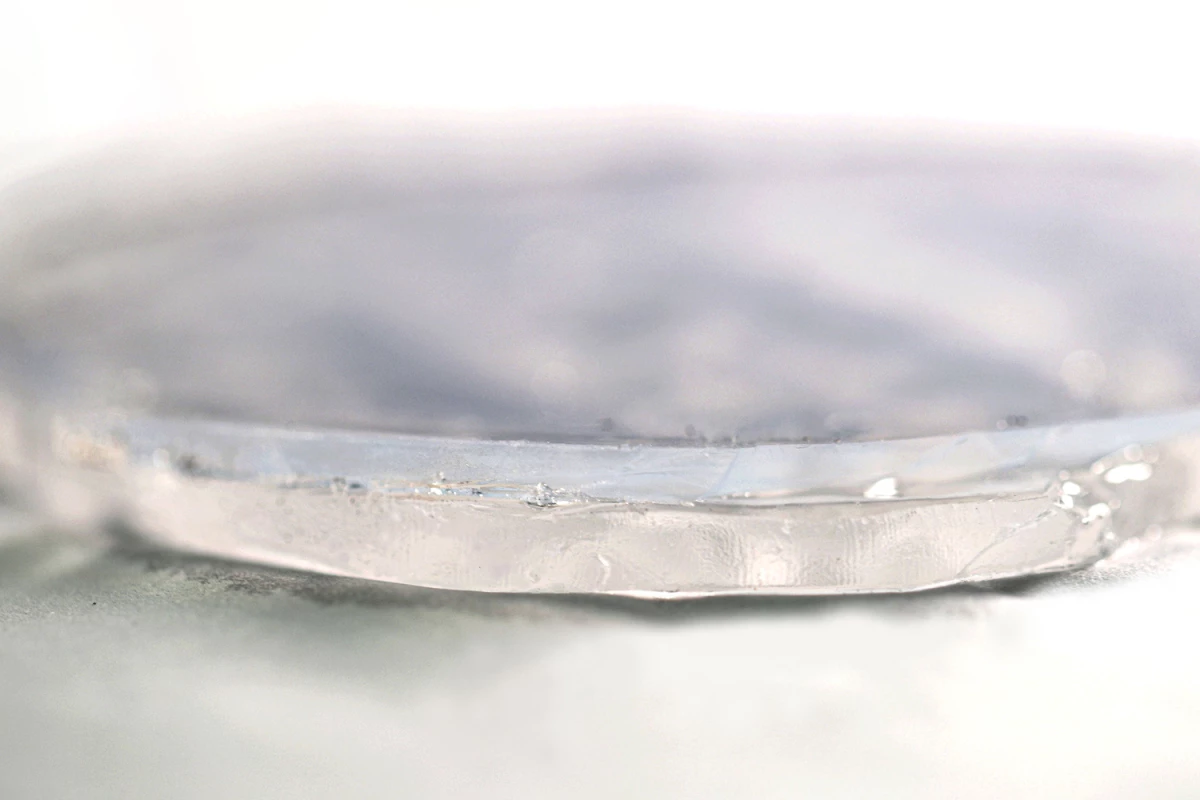

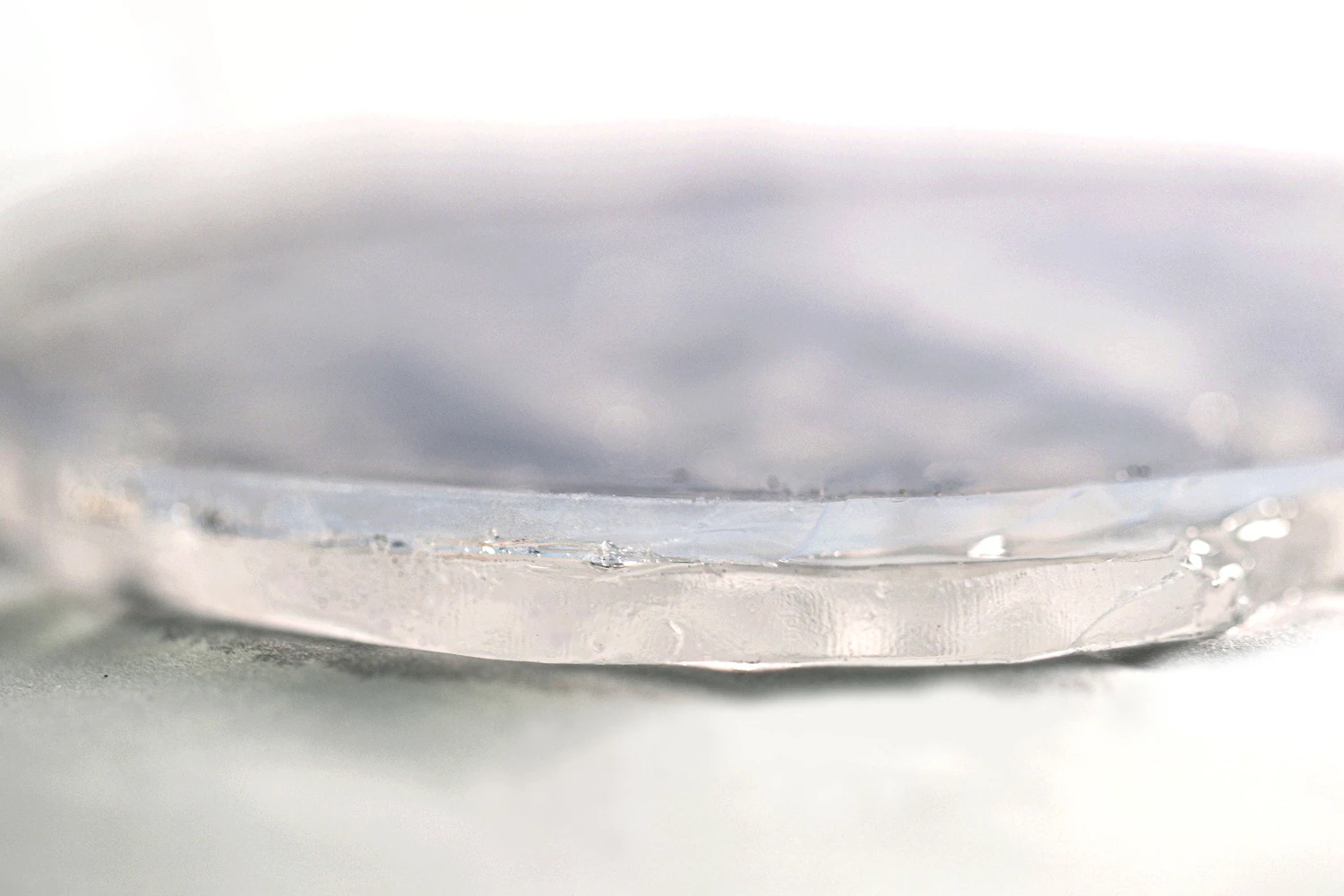

MIT's material works in a similar fashion, as it consists of a layer of hydrogel on the bottom, covered with a layer of porous silica-based aerogel on top. The hydrogel is made up of 97 percent water, which evaporates as the gel heats up, thus lowering that gel's temperature.

The aerogel has very low thermal conductivity, meaning that it doesn't absorb much heat from its environment. This means that the hydrogel beneath it stays cooler than it would otherwise, so its evaporative cooling effect is prolonged.

In lab tests, a bare 5-mm layer of the hydrogel lost all of its water to evaporation within 40 hours, at an ambient temperature of 30 ºC (86 ºF). Once that hydrogel was covered with a 5-mm layer of the aerogel, however, it lasted for 200 hours at the same temperature before becoming parched. The evaporative cooling effect lowered the composite material's temperature by 7 ºC (12.6 ºF), as compared to 8 ºC (14.4 ºF) for the bare but shorter-lasting plain hydrogel.

Additionally, once the hydrogel does dry out, the cooling material can be made functional again simply by adding more water.

Production of the aerogel currently involves large and expensive equipment, so the researchers are looking into more practical, less costly alternatives. Ultimately, it is hoped that the camel fur-inspired material could find use in developing nations or other places lacking infrastructure, for the shipping and storage of food and medicine.

The research is described in a paper that was recently published in the journal Joule.

Source: MIT