For many people, injection needles can be scary – and the larger ones for specialized longer-term medications are far more intimidating.

Many long-lasting drugs typically need to be delivered through alarmingly large needles. That's because they are administered in large doses, containing polymers which help create medication depots under the skin; those polymers can make up anything from 23% - 98% of the injectable solution by weight.

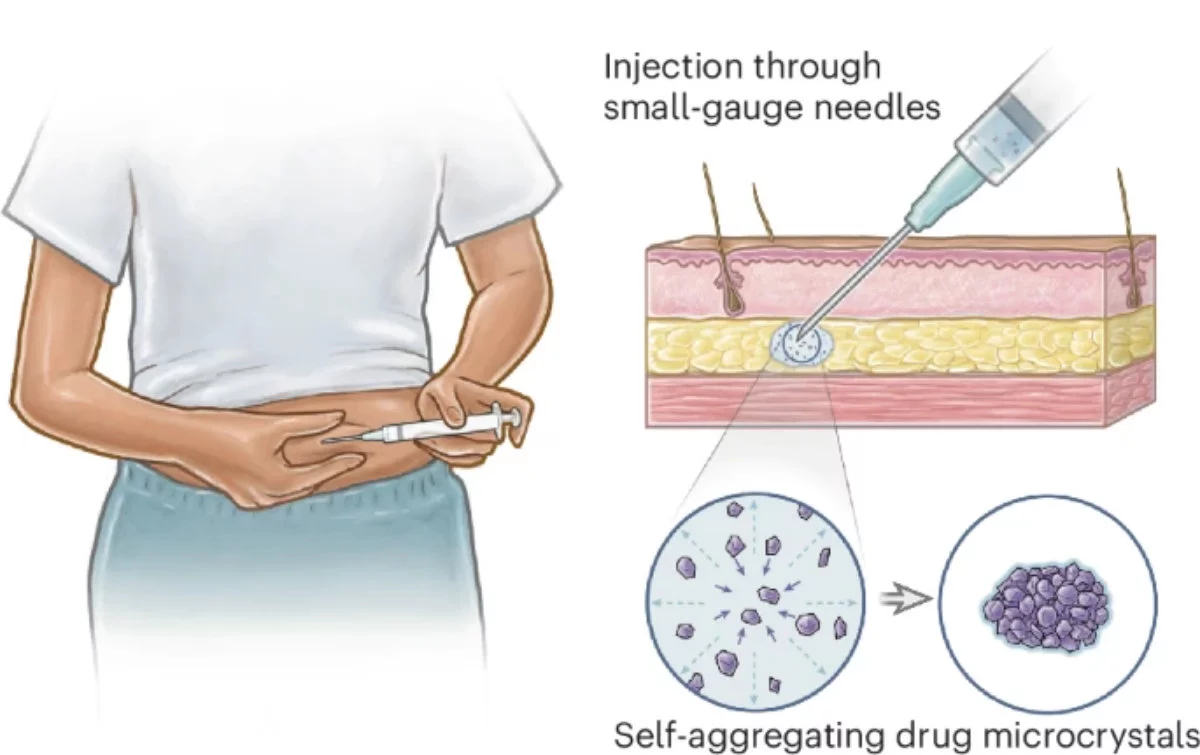

Reducing the amount of polymer needed would mean you could deliver the necessary dose using a less frightening narrow-gauge needle. That's why a diverse team of researchers set out to create a better way to deliver drugs into patients' systems, and it involves turning those drugs into tiny crystals that self-assemble into clusters.

For this study, the researchers – who hail from Stanford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – went with a contraceptive called levonorgestrel (LNG), which has molecules that are hydrophobic, i.e. they repel water. They can also form crystals.

In this approach, dubbed Self-aggregating Long-acting Injectable Microcrystals (SLIM), the idea is to create little crystals of this medication and suspend them in a special solvent. For the latter, the team landed on benzyl benzoate, which mixes awfully slowly with surrounding fluids once this formulation is injected just under the skin, and enables the crystals to aggregate into a solid 'depot' of medication to slowly release into the patient's bloodstream.

That also greatly reduces the need for a whole lot of polymer in the long-lasting formulation. In fact, just a small quantity of it – less than 1.6% to be precise – helped alter the density of the depot, which in turn controlled the rate at which the drug molecules were released into the body.

The researchers studied their formulation in rats over 97 days, and found more than 85% of the medication intact in the depot under their skin. That means they could potentially use this method to deliver drugs that need to be released over the course of six months to two years, with reasonably sized needles for a change.

While this approach has been proven to work with a particular combination of a contraceptive and a biocompatible solvent, the team believes it could also extend to treatments for HIV and tuberculosis. A method to deliver drugs over a longer period of time is not only useful for specific conditions like these, but can also be crucial for people in remote areas, who may only have sporadic access to medical care.

The researchers have published their findings in a paper that appeared in Nature Chemical Engineering, and their next step is to see how well this translates to humans, with preclinical studies. Anything that means smaller and/or fewer needles gets a nod from me.

Source: MIT News