When the heart is injured it can’t repair itself, meaning that heart failure often requires a transplant of the whole organ. But now, scientists at EPFL have developed an artificial aorta that can help pump blood, taking some of the pressure off the heart and reducing or even eliminating the need for a transplant.

After a heart attack or similar injury, the heart patches itself up with scar tissue. That’s good in the short term for keeping the structure intact, but unfortunately that scar tissue doesn’t beat. That means the heart can’t beat as well as it used to, putting extra strain on it that can eventually lead to full heart failure and the need for a whole organ transplant. But of course, donated hearts aren’t easy to come by.

So for the new study, the EPFL researchers investigated ways to assist a patient’s own heart for longer. And to do so, they turned to the aorta.

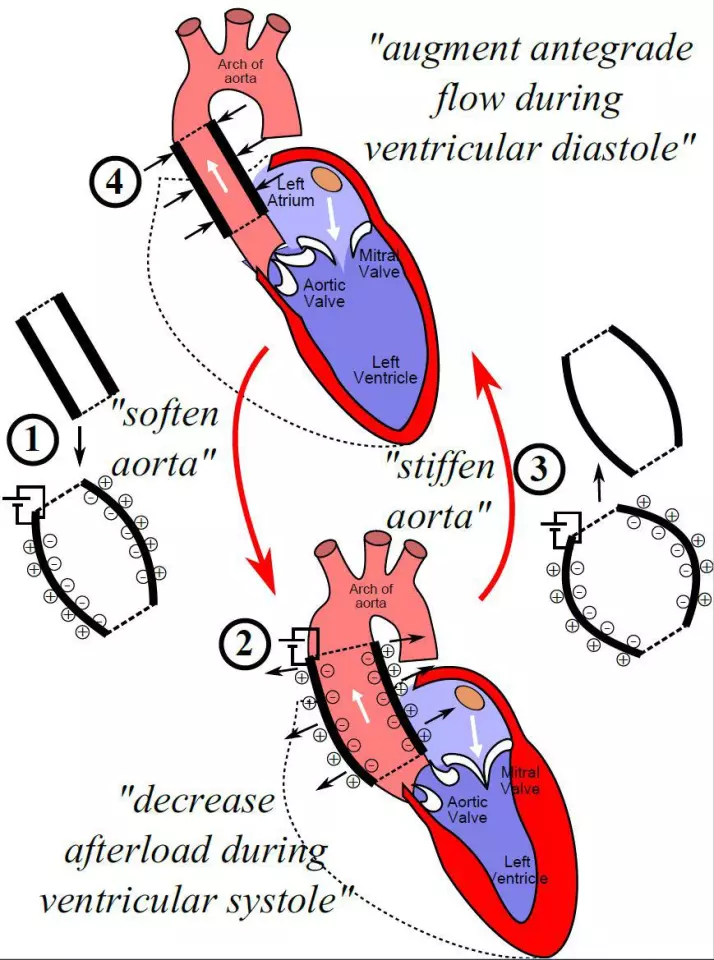

The aorta is the main artery that transports blood out of the heart to the rest of the body. To do that important job, the tissue is very elastic, swelling up as blood is pumped into it from the heart then contracting to squeeze it out to where it needs to go. The team designed an implantable artificial aorta that could do this job better, taking some of the strain off the heart.

“The advantage of our system is that it reduces the pressure on a patient’s heart,” says Yoan Civet, an author of the study. “The idea isn’t to replace the heart, but to assist it.”

The device is made up of a silicon tube complete with a set of electrodes, and it’s designed to be implanted right at the beginning of the aorta, just behind the aortic valve. When an electric voltage is applied, the tube swells up wider than a natural aorta would, so it can hold more blood. Then the voltage can be switched off, making the artificial aorta stiffen again to pump the blood out.

The team tested the device in a lab model of the human circulatory system, made using pumps and chambers that simulate realistic human blood flow and pressure. And sure enough, the artificial aorta reduced the cardiac energy required by 5.5 percent.

That might not sound like much, but for a proof of concept it shows that it can work. The next steps, the team says, is to improve the design to boost performance.

The research was published in the journal Advanced Science.

Source: EPFL