A chronic condition that occurs when the pancreas stops making insulin (type 1) or the body can’t effectively use the insulin it makes (type 2), diabetes can lead to a raft of complications. The disease, which affects hundreds of millions of people globally, was the focus of much research in 2023, resulting in a few ‘world-firsts’. From trialing a diabetes-slowing tablet to using plant extracts and creepy crawlies to lower blood sugars, here are the year’s top diabetes stories to grace our pages over the past year.

Speaking of diagnosing type 2 diabetes, there’s an app for that!

Usually, being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) requires having blood drawn and waiting for a test result. But that may soon change.

Discovering that voice features like pitch and intensity differed subtly between diabetics and non-diabetics, researchers developed an app that recorded a person speaking into their smartphone for 10 seconds, analyzed it using an AI-based program, and determined whether they had T2D with up to 89% accuracy.

A blood-sugar-lowering compound in your front garden

A team at The University of Otago proved that the dahlia is more than just a pretty addition to the garden; it also targets the glucose-regulating parts of the brain that are inflamed in type 2 diabetics to help stabilize blood sugar levels.

In a first-in-human trial, the researchers gave an extract of dahlia petals to people with T2D or prediabetes – where blood sugar levels are higher than normal but not high enough to warrant a diagnosis of T2D – and found that while it lowered blood sugars in both groups, it had a more profound effect on type 2 diabetics.

Here’s the hook(worm): a novel diabetes treatment

Another world-first human trial was undertaken in 2023, using something less pretty than a dahlia to improve blood sugars in type 2 diabetics.

Participants were given either 20 or 40 microscopic larvae of the human hookworm species Necator americanus, with another group taking a placebo. Those given 20 intestinal parasite larvae saw levels of insulin resistance drop to a healthy range, meaning that their cells were better able to respond to the insulin produced by the body. Participants who were given 40 also saw a drop, but it was less pronounced.

Participants were so enamored of their gut buddies and the good they were doing that all but one decided to hang on to them after the trial concluded (and that lone participant only decided to say good-bye to their hookworm because they had an impending medical procedure planned).

Centuries-old tonic found to be a benefit to diabetics

Thought to have originated in China before spreading to Russia, Eastern Europe and Germany, kombucha is produced by the fermentation of sugared tea using a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast. And it’s now enjoyed by many for its zingy taste and reputed health benefits.

While many of the health benefits claimed by kombucha fans have yet to be backed up by science, one has been. In a small study of 12 type 2 diabetics, half were given kombucha to drink for four weeks, while the other half drank a placebo; then they swapped. Both groups ate their normal diets. Kombucha drinkers saw a drop in fasting blood sugar levels to the recommended healthy zone.

World-first tablet: Progress is slowing disease progression

In type 1 diabetes (T1D), the destruction of the pancreas’ insulin-secreting (beta) cells occurs over time, meaning there’s a window early in the disease where they can still produce the essential hormone.

Knowing this, researchers repurposed a drug commonly prescribed for rheumatoid arthritis and found that, if given to type 1 diabetics within the first 100 days of diagnosis, it protected the still-functioning cells, preserving the body’s own insulin production and slowing the disease’s progression. The daily tablet was effective for almost one year (48 weeks).

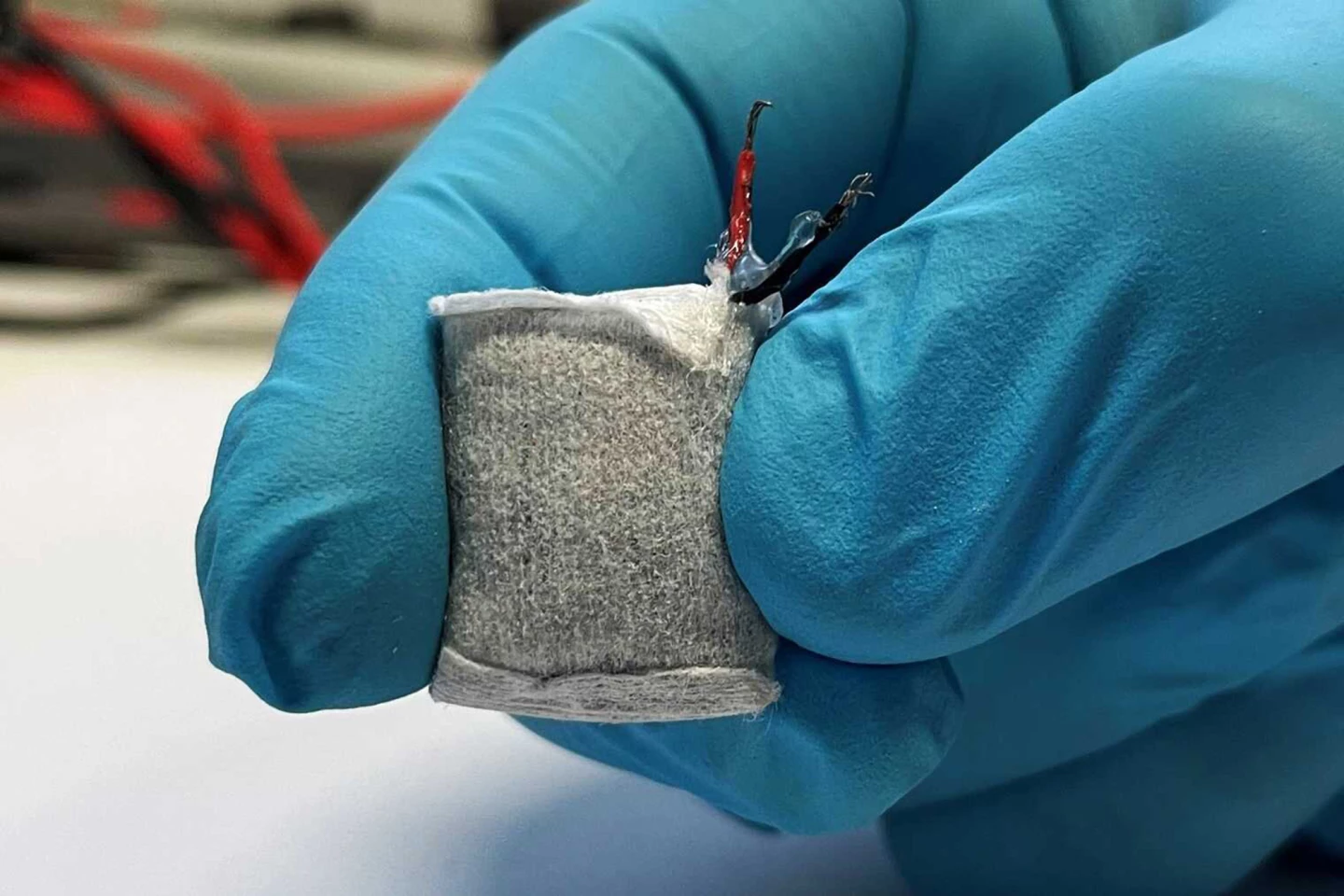

Powered by glucose, this ‘teabag’ regulates insulin production

Slightly larger than a fingernail, this under-skin implant that looks a lot like a teabag converts circulating glucose into an electric current to power a biomedical device connected to artificial beta cells. The implant’s current triggers the cells to secrete the insulin that type 1 diabetics require. It’s self-regulating: when the glucose-powered fuel cell senses excess blood sugar, it powers up; when blood sugars dip, it powers down.

Treatment without fear of rejection

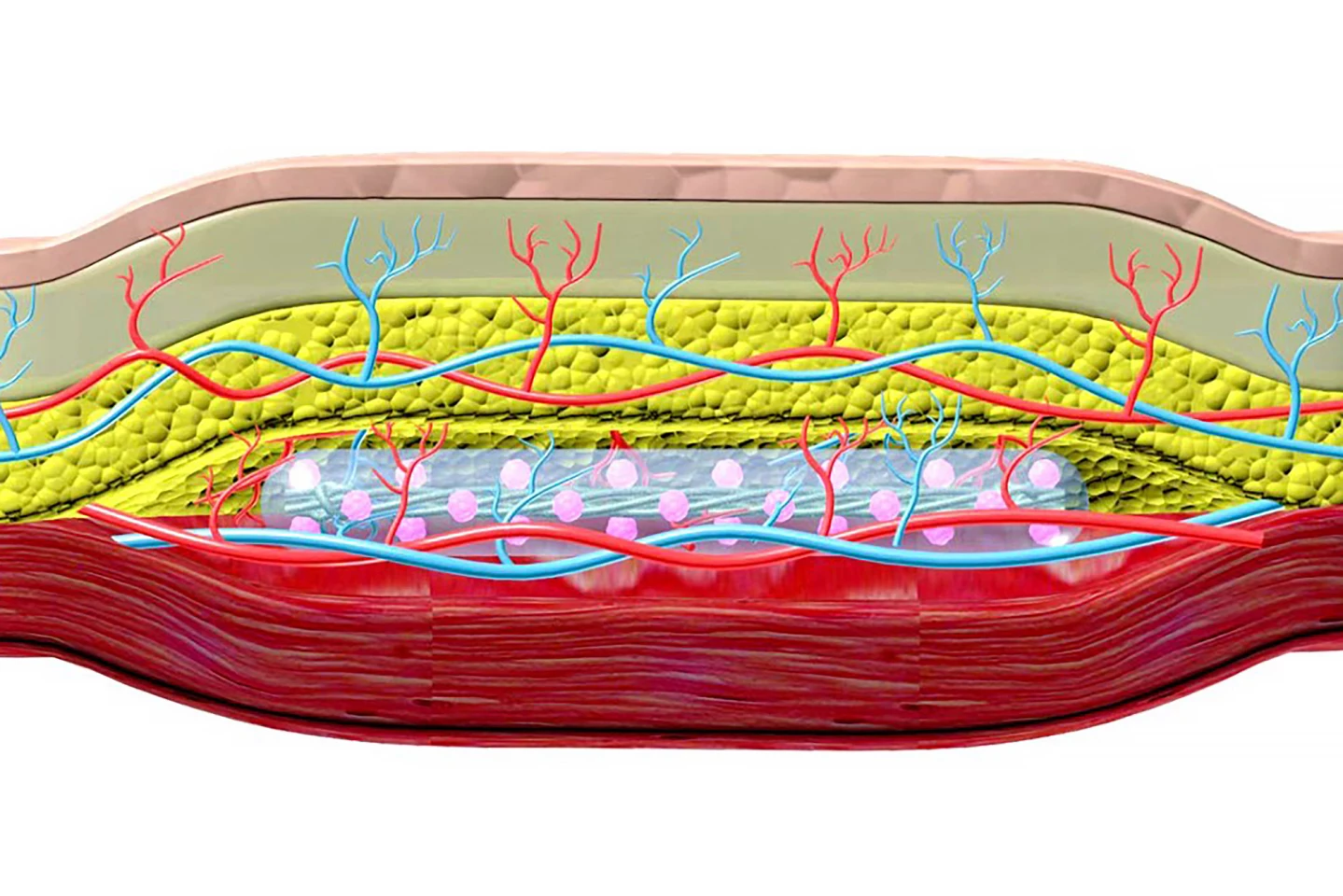

Another research team developed a subcutaneous implant for type 1 diabetics containing hundreds of thousands of insulin-secreting pancreatic cells encapsulated in hydrogel. It requires a two-step process: inserting nylon catheters under the skin for four to six weeks to create a pocket, then popping the implant into it – like a hand into a glove.

Creating the pocket triggers a foreign-body inflammatory response that causes a dense network of blood vessels to form around the ‘hole’ to provide nutrients and oxygen to the incoming implant. And, because the body has already encountered the foreign body, it’s unlikely to produce an immune response when the implant is introduced, removing the need for anti-rejection drugs often needed with body implants. Tested in diabetic mice, the implant corrected high blood sugar in some animals for more than 190 days and could easily be removed and replaced.

Stem cell transformation: From stomach cells to cells that secrete insulin

By forcing the activation of proteins that control gene expression, researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine successfully transformed hormone-producing stem cells taken from the stomach into pancreatic beta-cell-like insulin-secreting cells. When transplanted into mice, they behaved much like real beta cells, responding to rises in blood sugar by secreting insulin to keep the sugar levels steady, continuing to do so for six months.

Wound fluids provided crucial info about a common complication

Quicker wound development and slower healing are characteristics of diabetes, which increases the risk of infection and, in the worst-case scenario, leads to limb amputation. Collecting and analyzing the fluids that oozed from the wounds of diabetic and non-diabetic patients, researchers gained an understanding of the mechanism underlying this common complication.

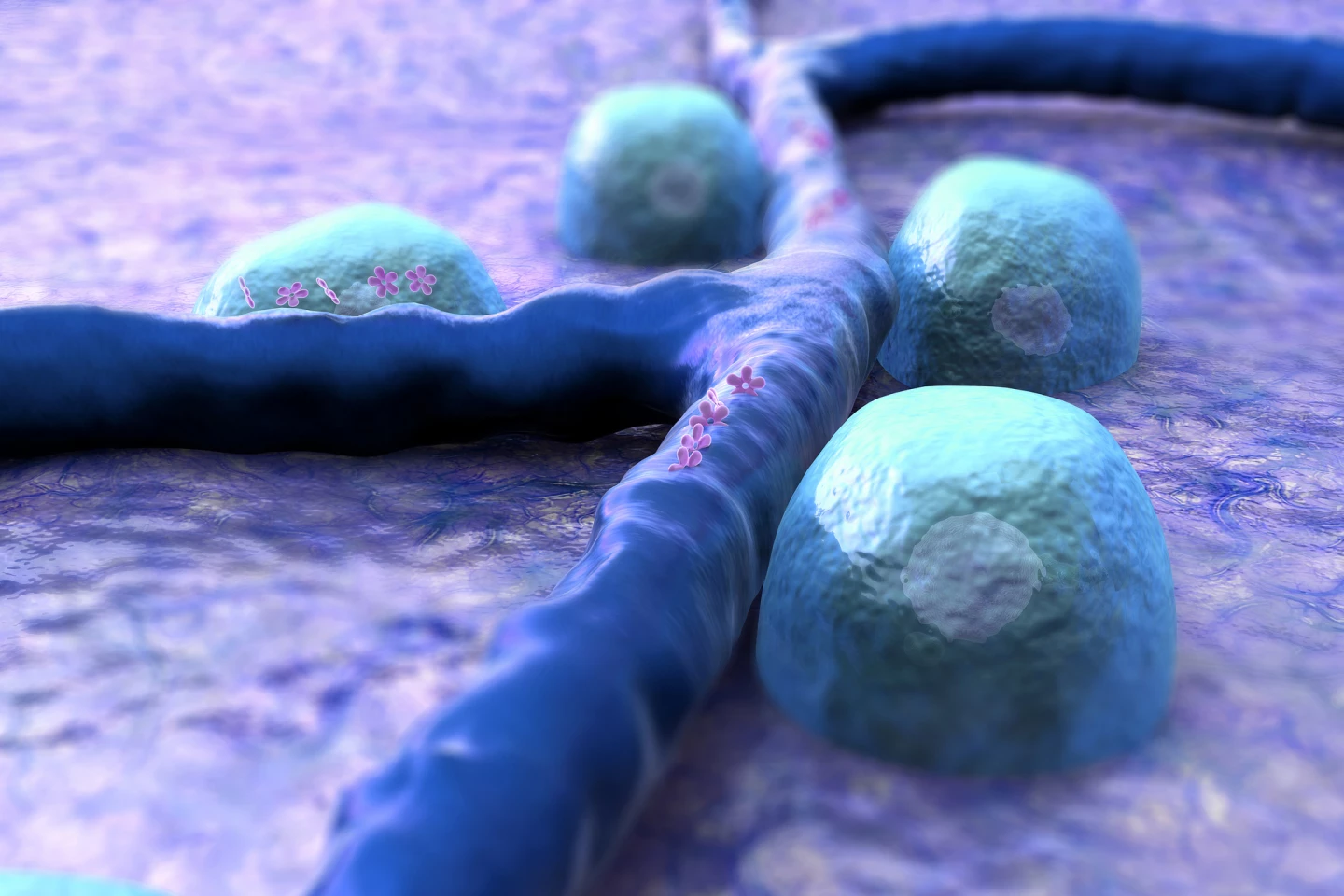

Messenger particles called exosomes deliver ‘cargo’ such as proteins, lipids, and genetic material to recipient cells, effectively altering that cell’s biological response. The researchers found that the number of exosomes in the wound fluid of diabetics, which they termed “diaexosomes”, was much lower. And, when the diaexosomes were incubated with macrophages, immune cells that coordinate wound healing, they produced a pro-inflammatory response. It was the opposite of what happened in non-diabetics, whose exosomes produced the ‘correct’ signal to macrophages to resolve inflammation and commence wound healing.

A way to wind back kidney damage

Over time, high blood sugars damage the kidney’s nephrons, tiny filtering units, so they’re less effective at filtering the blood to make urine. If the deterioration of kidney function, called nephropathy, continues for long enough, it can result in kidney failure.

Researchers identified a potential culprit for kidney damage: the protein interleukin-11 (IL-11). Noticing that when mouse kidneys sustained damage, the cells lining their tiny inner tubes released IL-11, which slowed cell growth and set off a molecular cascade of inflammation and scarring. However, the process was prevented by blocking IL-11 production, either by genetically engineering mice or by blocking it using an antibody. The kidney cells could proliferate again, which reversed scarring and inflammation and returned function to the organ.