Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have found that adding a booster protein can significantly improve the outcome of cancer immunotherapy. Tests in mice showed the protein produced 10,000 times more immune cells, with all mice surviving the entire experiment.

Our immune system is a powerful line of defense against disease, including cancer, but sometimes even it could use a hand. Enter CAR T cell immunotherapy, a promising new treatment where doctors extract T cells from a patient, genetically engineer them to target specific cancer cells, and return them to the body to hunt those cells down. While the technique has shown promise, the effectiveness can start to drop over time.

In the new study, the scientists investigated ways to combat this problem by boosting the number of T cells. To do so, they turned to a protein called interleukin-7 (IL-7), which the body naturally expresses to ramp up T cell production in the event of illness. The problem is, the natural protein normally doesn’t stick around very long, so the researchers modified it to circulate in the body for weeks.

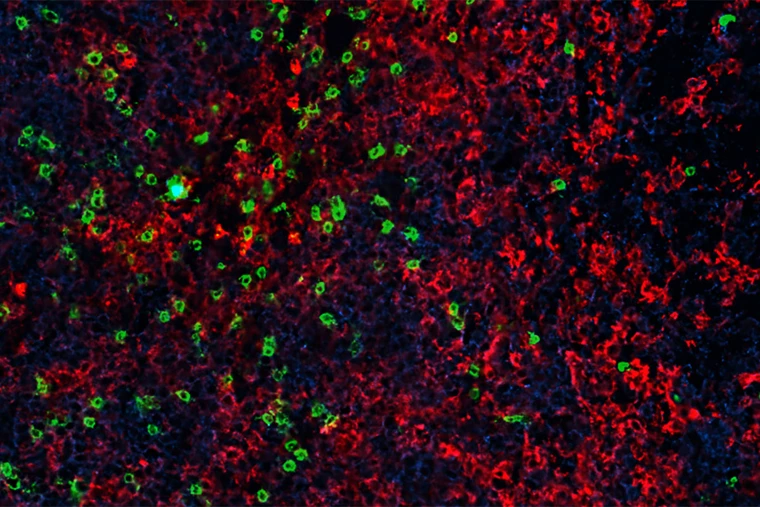

The team tested this longer-lasting IL-7 in mouse models of lymphoma, administering the protein on various days after the initial CAR T cell injection. When compared to control mice that received no immunotherapy, as well as others that received CAR T cell therapy without IL-7, the difference is stark.

“When we give a long-acting type of IL-7 to tumor-bearing immunodeficient mice soon after CAR T cell treatment, we see a dramatic expansion of these CAR-T cells greater than ten-thousandfold compared to mice not receiving IL-7,” said John DiPersio, senior author of the study. “These CAR T cells also persist longer and show dramatically increased anti-tumor activity.”

This boosted activity translated into increased survival for the treated mice. Every mouse that received CAR T cell therapy and IL-7 survived the entire 175 days of the experiment, with their tumors shrinking to the point of being undetectable by day 35. In contrast, mice that received immunotherapy alone survived just 30 days on average.

“In mice that received the CAR T cells alone, the disease is controlled briefly,” said DiPersio. “But by week three, the tumor starts to return. And by week four, they start to look like the control mice that didn’t receive any active therapy. But by adding long-acting IL-7, the numbers of CAR T cells just explode, and those mice lived beyond the time frame we set for our experiment. Our study also suggests that it may be possible to fine-tune the expansion of the CAR T cells by controlling the number of IL-7 doses that we give.”

As with any animal study, the results may not translate to humans, but the good news is that we may know sooner rather than later. Human clinical trials of IL-7-boosted CAR T cell therapy are set to begin soon in patients with a type of lymphoma.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.