For many, the idea of having a few dozen hookworms set up shop in your gut sounds more like a Survivor challenge than a beneficial health therapy, but scientists see a bright future in this human worm farm for treating many chronic conditions.

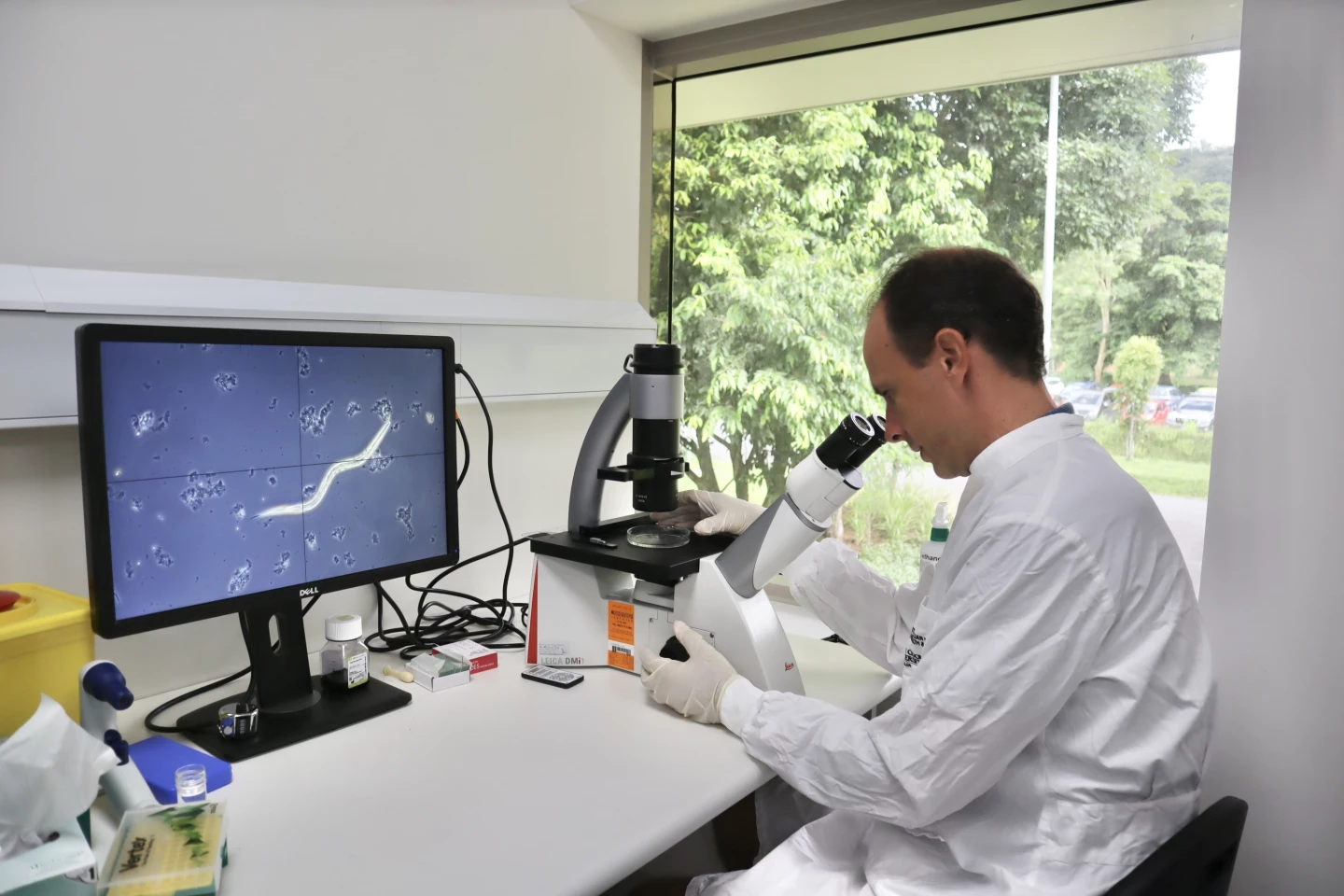

In a world first, a two-year human trial conducted by James Cook University (JCU) has wound up, and the worms graduated with flying colors, particularly in relation to type 2 diabetes, paving the way for a larger international trial.

What’s more, of the 24 participants who received worms, when offered a dewormer at the end of the second year of the trial, with the option to stay in the study for another 12 months, only one person chose to kill off their gut buddies – and it was only because they had an impending planned medical procedure.

“All trial participants had risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes,” said Dr Doris Pierce, from JCU’s Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine (AITHM). “The trial delivered some considerable metabolic benefits to the hookworm-treated recipients, particularly those infected with 20 larvae.”

Of course, not all hookworms are created equal, and much like bacteria, parasitic worms run the full gamut of human health interactions. But using low-dose human hookworm therapy is proving to have multiple benefits regarding the health of the host.

This latest study follows on from researchers using farmed, lab-grown hookworms to successfully treat chronic conditions such as Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) and celiac disease – the latter was also conducted by JCU scientists.

In this double-blinded trial, 40 participants aged 27 to 50, with early signs of metabolic diseases, took part. They received either 20 or 40 microscopic larvae of the human hookworm species Necator americanus; another group took a placebo.

“Metabolic diseases are characterized by inflammatory immune responses and an altered gut microbiome,” said Dr Pierce. “Previous studies with animal models have indicated that hookworms induce an anti-inflammatory response in their host to safeguard their own survival.”

As an intestinal parasite, the best survival skill is to keep the host healthy, which will provide a long-term stable home with nutrients ‘on tap.’ In return, these hookworms pay the rent in the form of creating an environment that suppresses inflammation and other adverse conditions that can upset that stable home.

While the small, round worms can live for a decade, they don’t multiply unless outside the body, and good hygiene means transmission risk is very low.

As for the results, those with 20 hookworms saw a Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) level drop from 3.0 units to 1.8 units within the first year, which restored their insulin resistance to a healthy range. The cohort with 40 hookworms still experienced a drop, from 2.4 to 2.0. Those who received the placebo saw their HOMA-IR levels increase from 2.2 to 2.9 during the same time frame.

“These lowered HOMA-IR values indicated that people were experiencing considerable improvements in insulin sensitivity – results that were both clinically and statistically significant,” said Dr Pierce.

Those with worms also had higher levels of cytokines, which play a vital role in triggering immune responses.

The researchers have now also moved onto looking at how this treatment may benefit gut microbiome health, and are testing samples from the 23 participants who retained their worms.

“Are some species of bacteria more or less common in the microbiome of people with insulin resistance and obesity? And does hookworm infection help redress any such imbalances?” Dr Pierce asked.

Interestingly, those with the worms self-reported better moods and overall felt healthier than those in the placebo group.

“The JCU trial provides sufficient proof of concept that infection with live hookworms is safe and appears to have some sort of beneficial effects on people’s metabolic health, which will hopefully be confirmed by future clinical trials designed to confirm efficacy and explore how hookworms influence metabolism,” said Dr Paul Giacomin, AITHM Senior Research Fellow and immunologist. “A wider, international trial will also allow us to gain a better understanding of the differential effects of hookworm infection on people of different ages, genders, races, and genetic backgrounds.”

It’s estimated a larger, international study would need funding of AU$1-2 million (US$640,000 to $1.3 million) to go ahead.

Dr Giacomin has also tabled the possibility of developing treatment, such as in a tablet form, that could provide the metabolic benefits of the parasitic worm without having to endure the infestation.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine