Heart disease is the number one cause of death in the United States and treatments are still surprisingly limited. Other than reducing cholesterol levels with statins, most treatments are indirect, such as preventing diabetes and high blood pressure, or improving diet and exercise.

New research led by a team from the University of Michigan suggests an immune protein may be a major causal factor in atherosclerosis, the thickening of arteries in the heart. And this discovery opens up the possibility of a range of new kinds of treatments targeting a condition that in some way affects almost every human as they get older.

“Targeting the immune component central to the development of atherosclerosis is the Holy Grail for the treatment of heart disease,” explained Salim Hayek, senior author on the new study “This is the first time that a component of the immune system is identified that meets all the requirements for being a promising treatment target for atherosclerosis.”

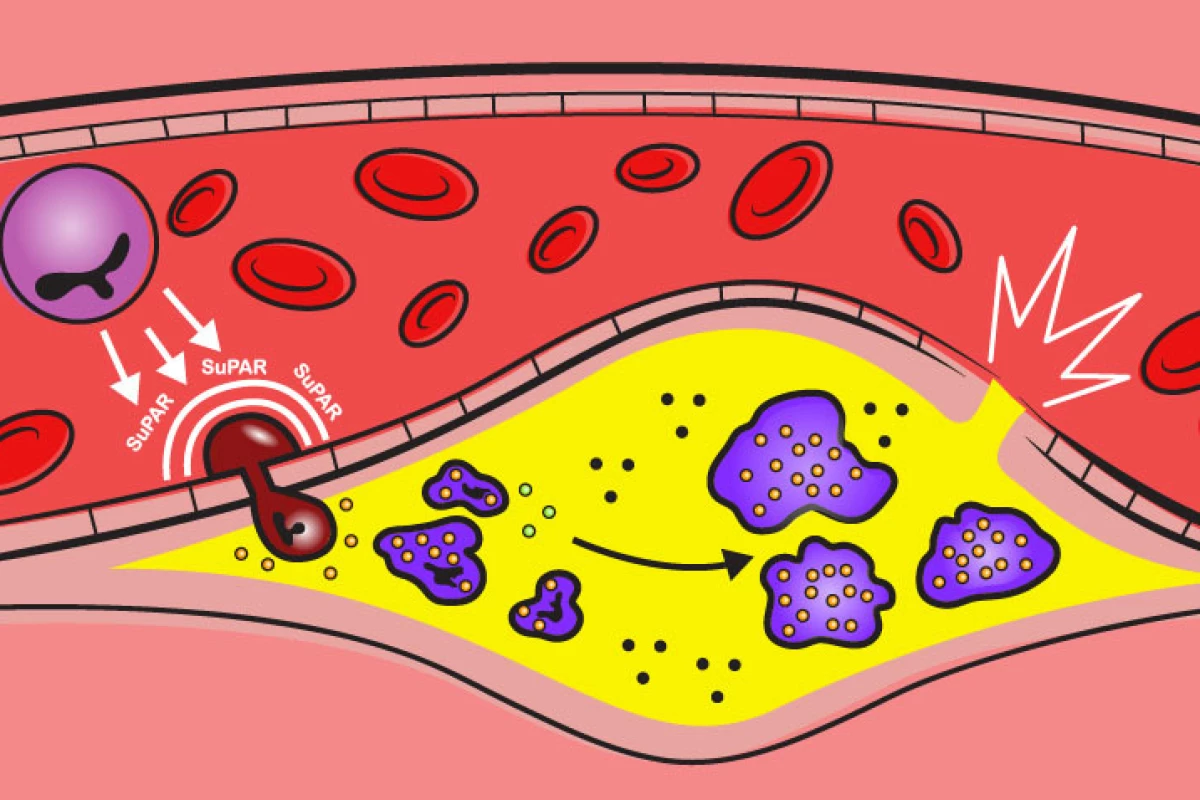

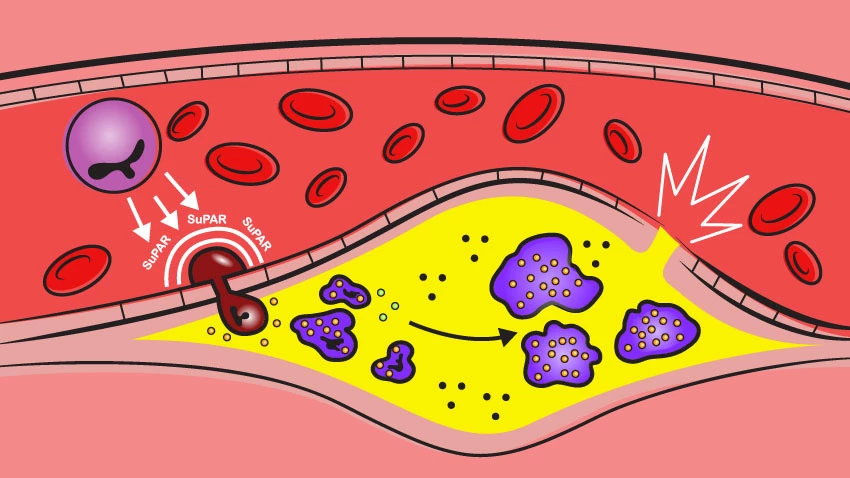

The new research focused on an immune protein called suPAR (soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor). The protein is produced by bone marrow and functions as a general regulator of immune system activity.

For years, researchers have known suPAR to be an effective immune activity biomarker. High levels of suPAR have been associated with everything from cancer to diabetes but most recently the immune protein has been found to play a causal role in kidney disease. Preclinical studies have found inhibiting suPAR can prevent, or even reverse, kidney injury, indicating the protein may be more pathogenically linked to disease than previously thought.

This new study set out to explore the potential for suPAR to be a causal agent in cardiovascular disease using three different approaches. First, the researchers looked at a cohort of 5,000 people from an ongoing atherosclerosis study. Here they found higher suPAR levels were significantly linked with greater rates of cardiovascular events.

The next step in the research was to look for any potential genetic variants that could influence suPAR levels. Looking at a dataset comprising 24,000 people, the researchers found a particular variant in a gene dubbed PLAUR could be linked with higher blood suPAR levels. And, tracking that gene variant in 500,000 people the researchers found it could be linked with higher rates of atherosclerosis.

"We also found that participants lacking a copy of the PLAUR gene have lower risk of heart disease,” said George Hindy, first author on the study. “Altogether, the genetic data is truly compelling for high suPAR being a cause of atherosclerosis.”

The final piece in the puzzle was working out how suPAR could be contributing to the development of atherosclerosis. Here, the researchers over-expressed levels of suPAR in mouse models of atherosclerosis. They found plaques in the arteries of the animals dramatically increased relative to suPAR levels. And according to co-first author Daniel Tyrrell, it seemed suPAR actually contributed to the process of artery calcification.

“High suPAR levels appear to activate the immune cells and prime them to overreact to the high cholesterol environment, causing these cells to enter the blood vessel wall and accelerate the development of atherosclerosis," Tyrrell explained. “Even prior to developing atherosclerosis, the mouse aortas with high suPAR levels contained more inflammatory white blood cells, and the immune cells circulating in blood were in an activated state, or ‘attack-mode.’”

Ultimately, these novel findings point to an entirely new way to treat heart disease. Inhibiting suPAR could plausibly decrease one's risk of cardiovascular disease and there are therapies already in development trying to do exactly that.

Monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors targeting suPAR have shown promising results in preclinical studies focusing on kidney disease. And a blood treatment therapy called plasmapheresis has been seen to both reduce suPAR levels and stabilize serious kidney disease in human patients.

Hayek said it will be crucial to find ways to safely reduce suPAR levels but he and colleagues are already working on designing targeted therapies.

“My hope is that we are able to provide these treatments to our patients within the next three to five years,” he said. “This will be a game changer for the treatment of atherosclerotic and kidney disease”.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Source: University of Michigan Health