One of humanity’s biggest threats is also the smallest – bacteria. With antibiotic resistance on the rise, we may be heading towards a future where even minor infections become lethal again. But now, researchers at RMIT in Australia have found a new method for killing these superbugs that they can’t resist – magnetic nanoparticles that physically tear them to shreds.

The ability for populations of bacteria to develop resistance to drugs is basic evolution. When a patient takes antibiotics, the majority of the offending bacteria will be wiped out – but not all of them. Some individuals will have random genetic mutations that let them survive the onslaught, and since they’re now the only ones left, these genes will be passed onto their offspring. In time, that resistance trait becomes the norm for that species, and the drug becomes ineffective against them.

Over the decades, the solution to this problem has been to develop new antibiotics, but the pipeline is beginning to run dry. New drugs are always in development, but it’s never enough, it takes too long, and they often don’t stay effective for very long. It’s clear that other methods are needed.

Enter the RMIT team. Rather than fight with chemicals, which bacteria will almost always develop resistance to, the researchers set out to find ways to physically attack the bugs. After all, humans, for example, could evolve resistance to mild poisons over time, but not being stabbed.

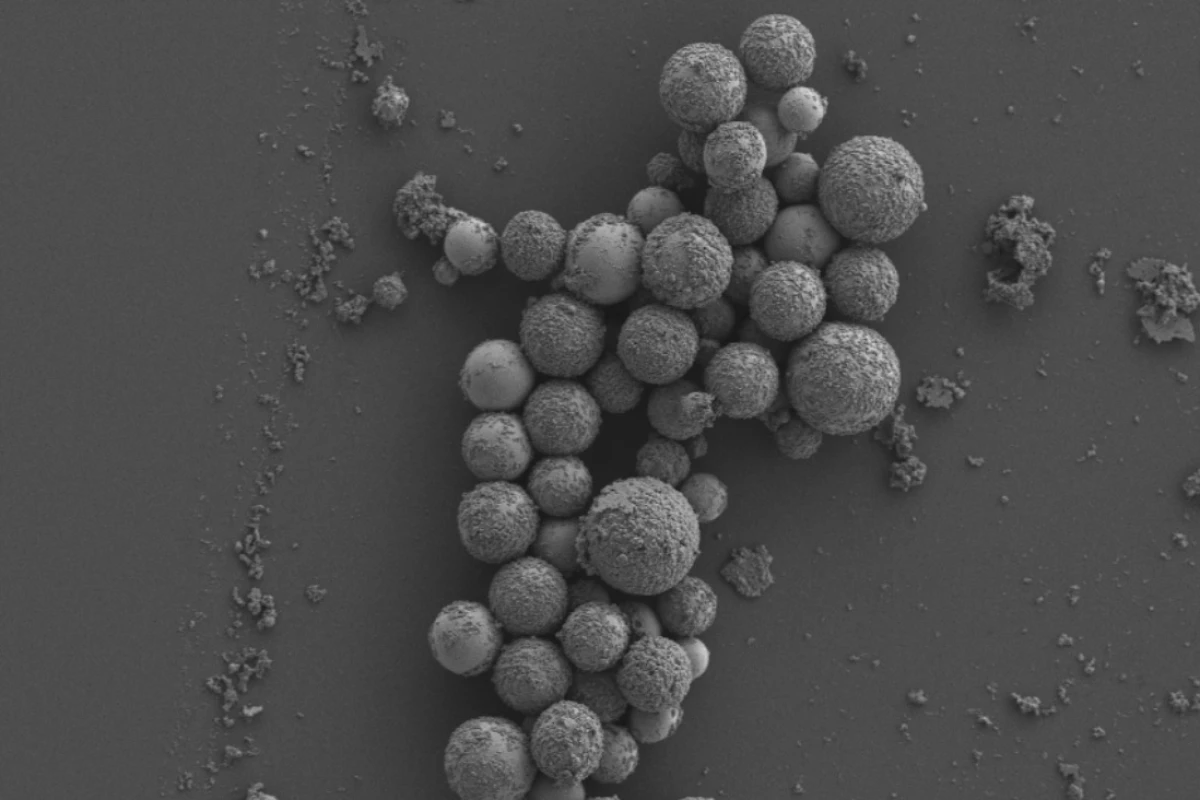

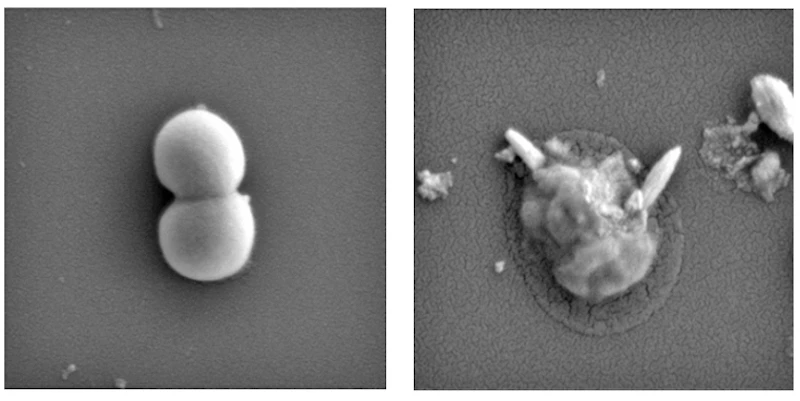

The team’s solution was to use magnetic, liquid metal nanoparticles. When exposed to a low-intensity magnetic field, these droplets change their shape, with their edges becoming sharp enough to puncture cell walls and biofilms – the sturdy, sticky substance that colonies of bacteria build to protect themselves from antibiotics.

In the lab, the team tested the new technique against bacterial biofilms. After 90 minutes, the biofilms were destroyed, as were 99 percent of the bacteria. This was shown to work against both main types of bacteria – gram-positive and gram-negative – and thankfully, didn’t harm human cells.

“Bacteria are incredibly adaptable and over time they develop defenses to the chemicals used in antibiotics, but they have no way of dealing with a physical attack,” says Aaron Elbourne, an author of the study. “Our method uses precision-engineered liquid metals to physically rip bacteria to shreds and smash through the biofilm where bacteria live and multiply. With further development, we hope this technology could be the way to help make antibiotic resistance history.”

The team says that the technology could be used as a spray coating for medical implants and instruments to keep them sterile, or potentially as an injectable treatment straight into the site of an infection. In the long run, it could be adapted to work against fungal infections, cholesterol plaques and even cancer.

As promising as it sounds, it’s very early days – the team is just now beginning to test the technology in pre-clinical animal trials, so it’ll be a while before human trials begin, if ever. Still, it could become a fascinating physical approach to the problem, alongside systems like materials, electrified graphene surfaces and decontaminating light.

The research was published in the journal ACS Nano.

Source: RMIT