Scientists have previously shown how to activate energy-burning brown fat in mice, which helps shed weight and improves health. Results have been hard to replicate in humans, but a new study has found that we might be targeting the wrong receptor in our bodies.

The form of fat that we’re all so frustratingly familiar with is white fat. This is the stuff that builds up around our bellies and thighs, as our bodies try to store excess energy for later. But it’s not the only type we have – there’s also brown fat, which burns stored energy to produce body heat, in a process called thermogenesis.

Scientists have been trying to find ways to convert white fat to brown, and activate it to burn energy. Such an advance could not only help us shed some pounds, but also treat obesity and related health problems like type 2 diabetes. While there’s been some success in mouse studies, human trials have largely failed to get results.

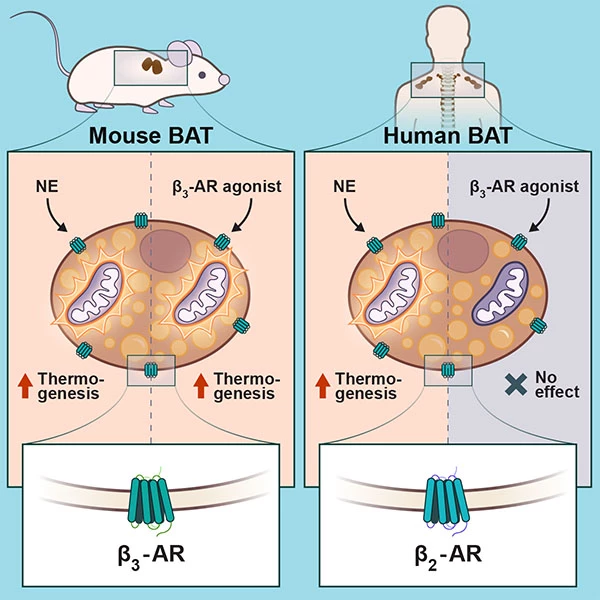

But now, researchers at the Universities of Sherbrooke and Copenhagen have found why that might be the case. In mouse studies, scientists have successfully targeted beta3-adrenergic receptors (b3-AR), but these don’t seem to work well in humans. Instead, the new study found that a similar receptor called b2-AR helps stimulate thermogenesis.

“We show that perhaps we were aiming for the wrong target all along,” says Denis Blondin, an author of the study. “In contrast to rodents, human (brown fat) is activated through the stimulation of the beta2-adrenergic receptor, the same receptor responsible for the release of fat from our white adipose tissue.”

With this new target identified, the researchers say that a further phase of study will begin in the coming months to find drugs that can activate this receptor to help burn off brown fat.

“Activation of brown fat burns calories, improves insulin sensitivity and even affects appetite regulation,” says Camilla Schéele, an author of the study. “Our data reveals a previously unknown key to unlocking these functions in humans, which would potentially be of great gain for people living with obesity or type 2 diabetes.”

The research was published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Source: University of Copenhagen