Researchers who’ve developed an oral insulin that has proven effective at reducing blood glucose and avoiding hypoglycemia in mice, rats, and baboons are set to take their drug to human clinical trials as soon as 2025. They’re hopeful it’ll be available to all in a few years.

New Atlas has covered a lot of research into oral insulin, from its development to testing in both animal and human trials. It’s understandable that scientists and researchers are invested in developing edible insulin, given that, in 2021, there were 537 million adults in the world living with diabetes – that’s one in 10 – with the number expected to rise to 643 million by 2030. But despite their best efforts, no oral insulin is available on the market.

Now, researchers at UiT The Arctic University of Norway have collaborated with University of Sydney researchers to develop an oral insulin that has already proven effective in animal models and is set to go to human clinical trials as soon as 2025.

“This way of taking insulin is more precise because it delivers the insulin rapidly to the areas of the body that need it most,” said Peter McCourt, one of the study’s co-authors. “When you take insulin with a syringe, it is spread throughout the body where it can cause unwanted side effects.”

Diabetics who use injectable insulin or continuous insulin infusions via pump do so to maintain strict blood glucose (glycemic) control, thereby reducing the likelihood of long-term complications such as cardiovascular disease or kidney, neurological, and eye diseases. But they also need to monitor for acute adverse events like hyper- (high) and hypoglycemia (low blood glucose), both of which carry significant health risks.

The researchers had previously found that delivering medication to the liver was possible using nanocarriers. In healthy people, the liver is where most of the insulin secreted by the pancreas acts. But their delivery system had to be able to survive the rigors of the stomach’s high acidity and the action of digestive enzymes, which can render medications ineffective.

“We have created a coating to protect the insulin from being broken down by stomach acid and digestive enzymes on its way through the digestive system, keeping it safe until it reaches its destination, namely the liver,” McCourt said.

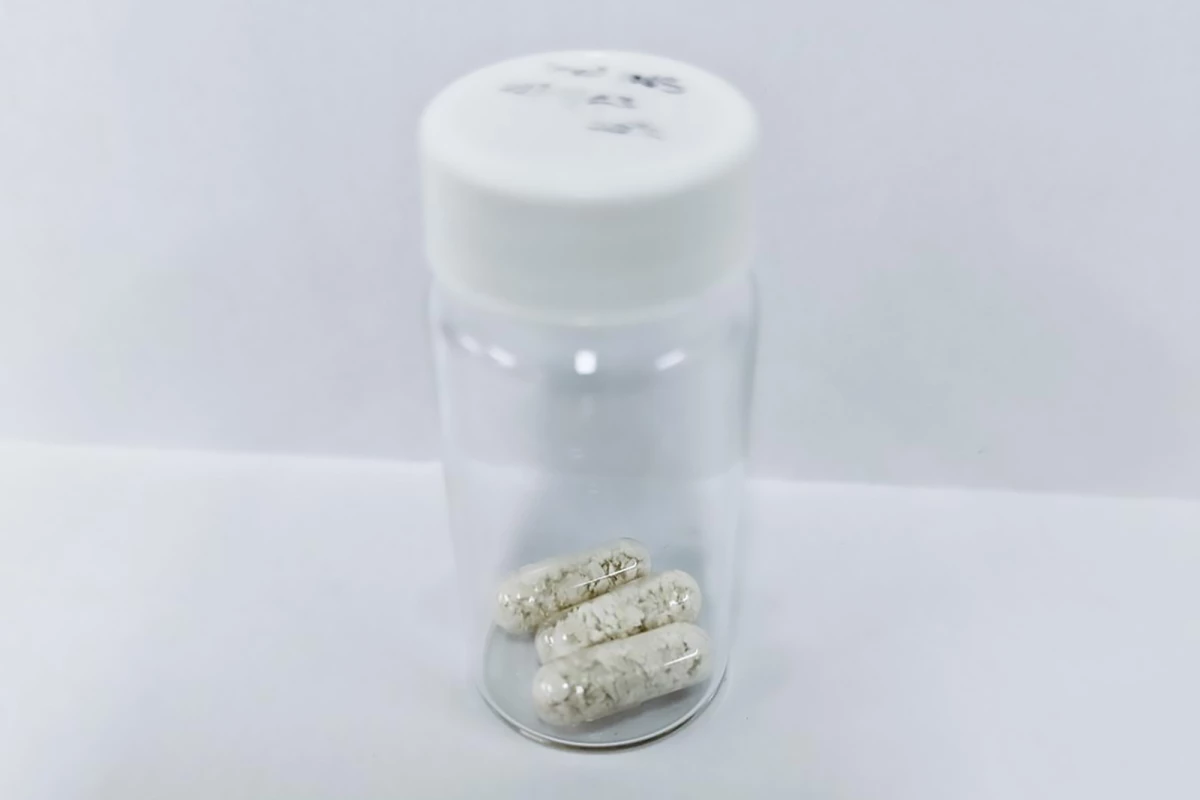

The researchers’ pH- and enzyme-sensitive coating, a chitosan and glucose copolymer, is applied to insulin bound to silver sulfide (Ag2S) quantum dots. The coating is broken down in the liver by enzymes that are only activated when blood glucose is high, releasing insulin to induce glucose storage in the liver, muscles and fat so it can be used as an energy source, removing it from the blood.

“This means that when blood sugar is high, there is a rapid release of insulin, and even more importantly, when blood sugar is low, no insulin is released,” said Nicholas Hunt, lead and co-corresponding author of the study.

The researchers tested their novel oral insulin on nematodes (C. elegans), mice and rats before moving on to baboons, who preferred to take their insulin with chocolate.

“In order to make the oral insulin palatable, we incorporated it into sugar-free chocolate; this approach was well-received,” Hunt said.

The researchers used their oral insulin on 20 healthy, non-diabetic baboons. Treatment with five international units (IU)/kg and 10 IU/kg of oral insulin produced a 10% and 13% reduction in blood glucose, respectively, with observable effects between 15 and 30 minutes. No hypoglycemia occurred in any baboons. Although the baboons were not diabetic, the researchers found that the rats and mice, who were, also did not have any hypoglycemic events following administration of the drug.

As well as being more practical and patient-friendly – no injections, more discreet, does not require refrigeration – the researchers say their drug’s method of action more closely mimics how insulin works in healthy people.

“When you inject insulin under the skin with a syringe, far more of it goes to the muscles and adipose tissues that would normally happen if it was released from the pancreas, which can lead to the accumulation of fats,” said Hunt. “It can also lead to hypoglycemia, which can potentially be dangerous for people with diabetes.”

All that remains is for the researchers to test their oral insulin on humans.

“Trials on humans will start in 2025, led by the spin-out company Endo Axiom Pty Ltd,” Hunt said. “Clinical trials are performed in three phases; in the phase I trial, we will investigate the safety of the oral insulin and critically look at the incidence of hypoglycemia in healthy and type 1 diabetic patients. Our team is very excited to see if we can reproduce the absent hypoglycemia results seen in baboons in humans, as this would be a huge step forward. The experiments follow strict quality requirements and must be carried out in collaboration with physicians to ensure that they are safe for the test subjects. After this phase I, we will know that it is safe for humans and will investigate how it can replace injections for diabetic patients in phase 2 trials.”

The researchers hope their oral insulin will be available for use in two to three years.

The study was published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.