To make sure vaccines work as efficiently as possible, it’s important to keep track of who has had which shots and when, but that’s not always easy, particularly in developing countries. So now, MIT researchers have come up with a creative new solution. A microneedle patch can administer both the vaccine and quantum dots that sit under the skin for years at a time, essentially storing a person's vaccine history on their own body.

A patient’s vaccination record is important to their health – and that of the community as a whole. Not only does it highlight which shots they still need, but many vaccines require multiple doses at specific intervals in order to work and losing track of that can lead to ineffective treatment. The new method from MIT is designed to change that, with an immediate focus on developing countries.

“In areas where paper vaccination cards are often lost or do not exist at all, and electronic databases are unheard of, this technology could enable the rapid and anonymous detection of patient vaccination history to ensure that every child is vaccinated,” says Kevin McHugh, lead author of the study.

The key to the new technique is a dye containing quantum dots, tiny semiconducting crystals that reflect certain wavelengths of light. The idea is that this would be administered along with a vaccine, and while the drug goes to work in the bloodstream the quantum dot dye would sit just below the skin for up to five years.

These dyes can be arranged into different patterns to mark different vaccines. That way, when a doctor needs to check a patient’s record, they can use a specially-equipped smartphone that makes the normally-invisible dye fluorescent and see what pattern shows up.

In this case, the quantum dots are copper-based, and designed to emit near-infrared light. To keep them in the body for long periods of time, the team encapsulated them inside microparticles about 20 microns wide.

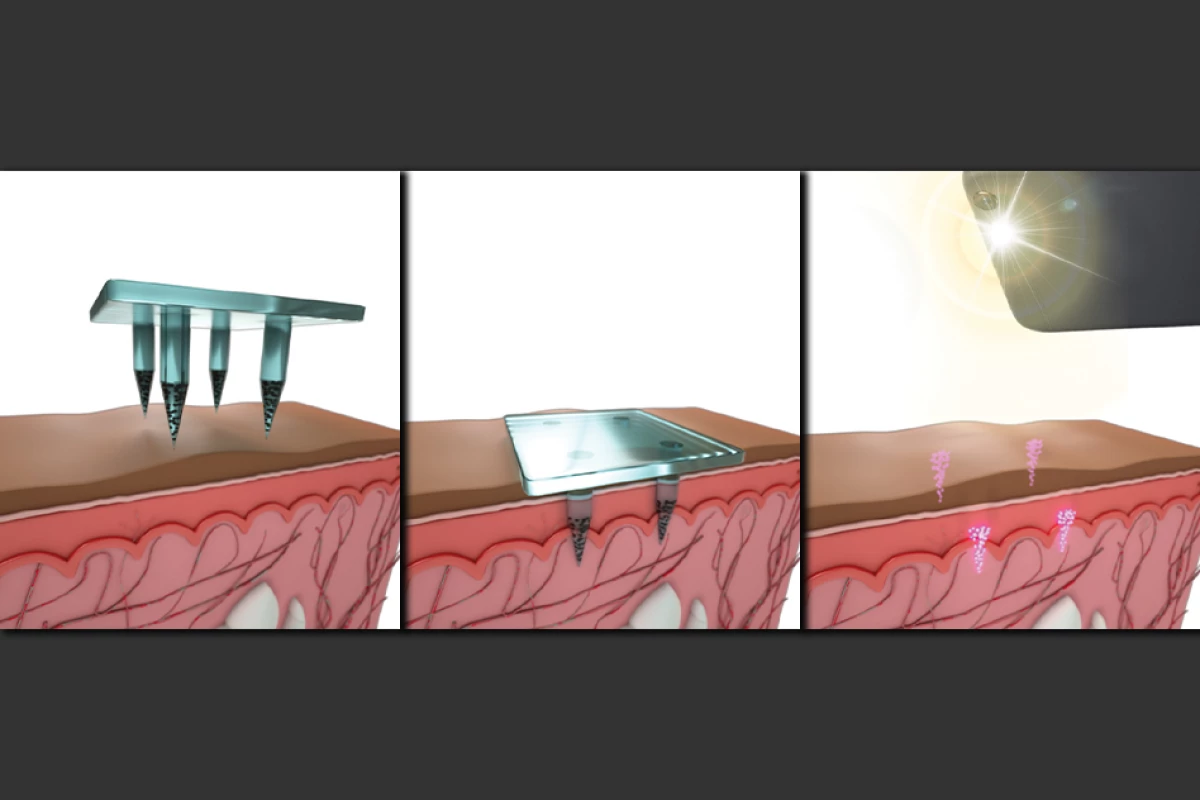

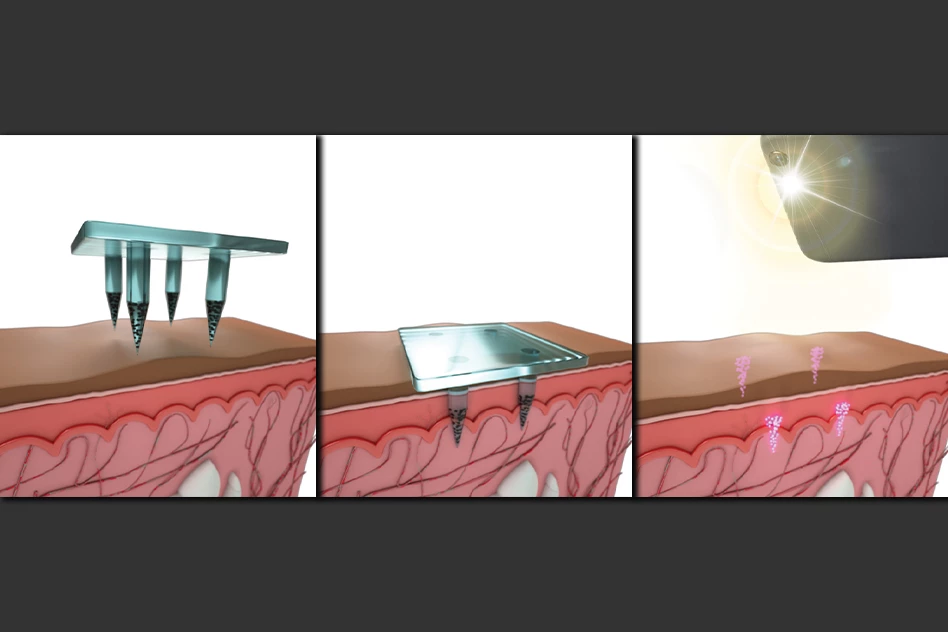

The team designed the dye to be delivered via microneedle patch. This painless alternative to a syringe is applied like a Band-aid, with the skin-facing surface made up of tiny dissolvable needles. The needles themselves are made of the desired drug and the quantum dots, all bundled together with sugars that dissolve and a polymer for structure. As the needles dissolve, they release the payload into the body.

In tests, the team used microneedle patches to administer the dye to samples of human skin from cadavers. Even after five years of simulated Sun exposure, the quantum dot patterns could still be seen by the smartphone detector.

In another test on rats, the quantum dots were found to not impede the effectiveness of a polio vaccine, and didn’t aggravate the animals’ immune systems any more than a regular vaccine.

In future, the researchers will work on incorporating more specific data into the patches, such as the date and batch number of the vaccination. More tests will also need to be done to ensure the dye is safe in humans.

The research was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Source: MIT