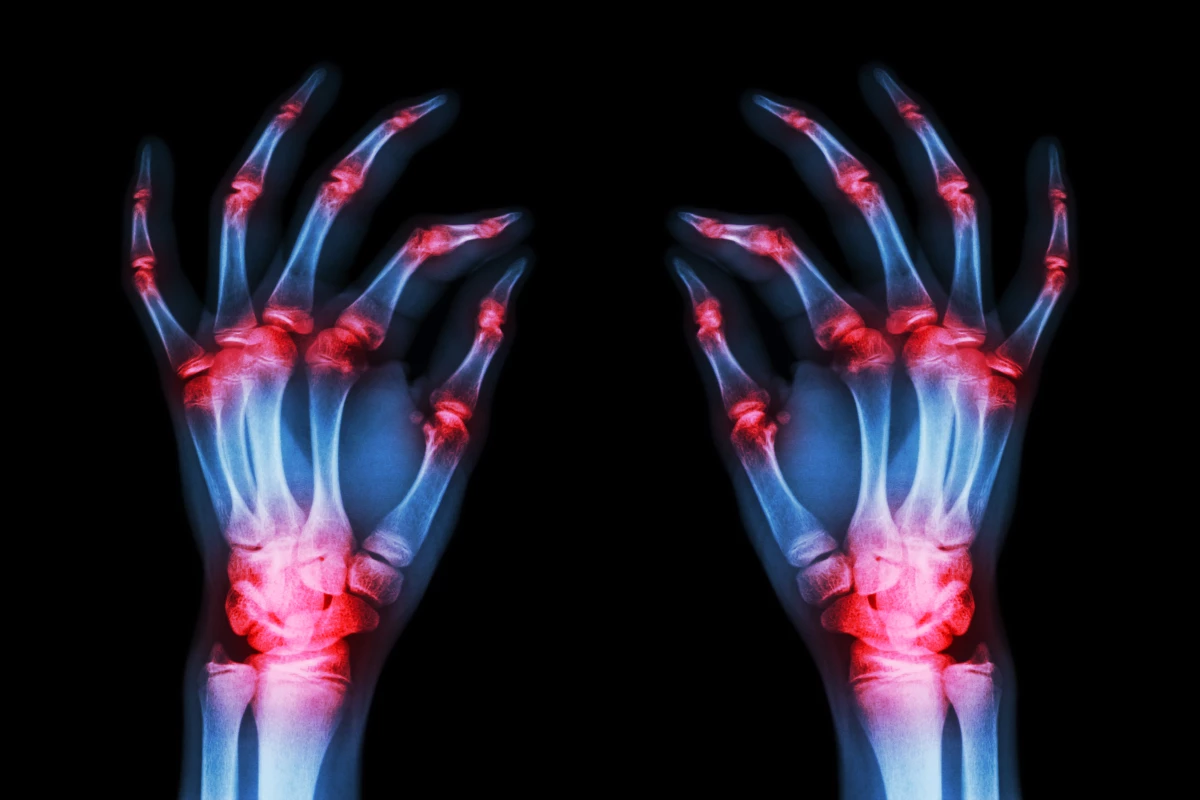

A team of researchers in the United States has discovered a novel mechanism in which a key protein drives the inflammatory damage associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The foundational finding is hoped to direct research toward entirely new pathways to treat this autoimmune disease affecting millions.

One of the most impactful rheumatoid arthritis discoveries over the past few decades was finding an immune cytokine called tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF-alpha) plays a crucial role in joint tissue inflammation. Following this discovery the development of monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors offered rheumatoid arthritis patients a completely new type of medicine to treat their condition.

But, as senior author on the new research Salah‑Uddin Ahmed explained, TNF inhibitors aren’t effective in all patients. And even then, they are not ideal long-term medicines dues to a variety of side effects.

“Tumor necrosis factor‑alpha – or TNF‑alpha for short – is one of the main inflammatory proteins that drive rheumatoid arthritis and is targeted by many currently available therapies,” said Ahmed. “However, over time patients can develop a resistance to these drugs, meaning they no longer work for them. That is why we were looking for previously undiscovered drug targets in TNF‑alpha signaling, so basically proteins that it interacts with that may play a role.”

The new lab-based research focused on a type of human cell called synovial fibroblasts. These are the cells that line joints, and in cases of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation in synovial fibroblasts is triggered by TNF-alpha.

In looking for a protein that plays a role in joint inflammation the researchers homed in on a molecule called sulfatase‑2. Prior cancer studies have indicated sulfatase‑2 plays a role in tumor growth, and it's known to be involved in immune cell signaling processes.

So the researchers hypothesized sulfatase‑2 could play a part in the way TNF-alpha triggers inflammation. To test this, the team removed the protein from synovial fibroblasts and then watched what happened when the cells were stimulated with TNF-alpha. Excitingly, the experiments revealed significantly reduced inflammatory responses in the cells when sulfatase‑2 was removed.

“Looking at sulfatases for their potential role in inflammation was an educated guess, but once we did we saw a very consistent pattern of increased sulfatase‑2 expression throughout different tissues and samples we studied,” said Ahmed. “This tells us that TNF‑alpha relies on sulfatase‑2 to drive inflammation, because as soon as we removed sulfatase‑2 the inflammatory effects of TNF‑alpha were markedly reduced.”

It’s important to note this research is still in very early stages. These findings are so far only established in cell models and further animal studies will be needed to validate these mechanisms before any kind of human treatment can be considered.

Nevertheless, this is an extraordinarily promising foundational discovery. And there is other ongoing work looking at blocking sulfatase‑2 to treat cancers. In fact, a sulfatase‑2 inhibitor is already in Phase 2 human clinical trials as a treatment for severe forms of brain cancer, so if this mechanism is further validated in rheumatoid arthritis it may not be a huge leap to get to testing these kinds of drugs for other inflammatory conditions.

The new study was published in the journal Cellular & Molecular Immunology.

Source: Washington State University