If aeroplanes can refuel each other mid-air, then why not electric cars? A weird and wonderful, if probably impractical, idea out of the University of Florida would see vehicles in high-speed convoy sharing energy in a peer-to-peer model.

As a foolish and curious motorcyclist, I can tell you it's amazing how little resistance you feel, and how far you can make a small amount of fuel last, when you foolishly snuggle yourself into the cocoon of low-pressure air dangerously close to the back of a truck. Don't try it, you can't see a damn thing. You'll run over potholes and road debris, you'll breathe in a lot of diesel fumes and you'll have almost zero time to respond if the truck hits the brakes. But the feeling is extraordinary, the headwind disappears and you're wrapped in a little bubble of warm, still air.

One of the great benefits of self-driving cars will be their ability to drive nose-to-tail like this at speed without taking any safety risks. Their drive computers will synchronize to act as a single vehicle and the aerodynamic efficiency benefits will be huge for the vehicles behind the front one.

But why should that front vehicle pay a higher energy price to push through the air while everyone else is enjoying the benefits of its wake? Maybe it won't have to, if a proposed energy sharing system takes off.

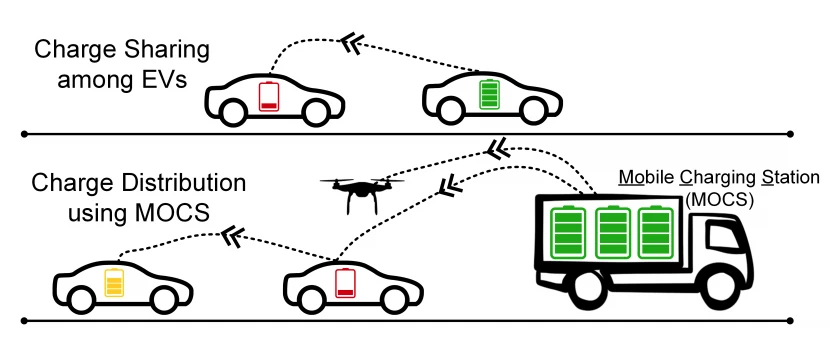

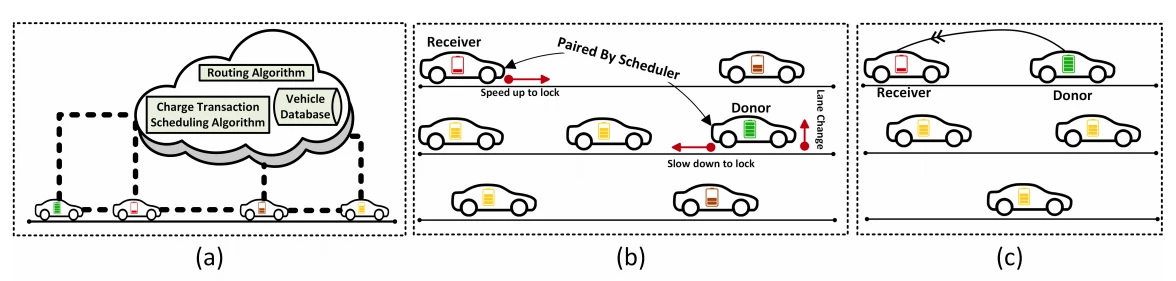

The Peer to Peer Car Charging (P2C2) system proposes that robotic charging arms could reach out to connect autonomous vehicles as they convoy along the freeway, using one vehicle's battery to charge the other up. "We envision a safe, insulated, and firm telescopic arm carrying the charging cable," reads a paper by the Florida team. "After two EVs lock speed and are in range for charge sharing, they will extend their charging arms... The arms' heads will contain the charging ports, and they will latch together using either magnetic pads or other means." A mechanical connection is one way of transferring charge, but wireless inductive charging might also be possible.

For individual EV owners, who rarely use up their whole battery in daily use, this could totally eliminate the need to pull over and fast charge at a charging station. A credit system could ensure nobody's taking advantage of energy somebody else has paid for, and then the entire traffic ecosystem suddenly becomes one giant, shared battery and nobody ever needs to stop their journey to refuel.

For a robo-taxi fleet operator – say, a future Uber Autonomous – the benefits could be huge. Instead of cars coming off the road to sit and charge in a garage, making no money, they could simply meet up with a big ol' battery truck for a top up on the way to their next destination.

The feasibility of this entire concept comes down to economics. Does it cost more to specify your robo-taxis with bigger, all-day batteries and charge them at a big facility in the downtime hours, or to run smaller batteries with mobile peer-to-peer charging when things are busy and cars need to stay on the road?

The team built a model of a mobile charge truck system, complete with multi-density traffic simulations, vehicle weights, off- and on-road charging rates and a rudimentary scheduling algorithm that allowed the simulated robo-taxis to call for charging assistance when they needed it. The simulation showed some impressive results, reducing vehicles stoppages by 65 percent and reducing the required battery capacity of the cars by just under 25 percent without causing any extra stops.

Now, does it cost more to implement a system like this than it'd save? Could you do things cheaper by buying a big ol' parking garage and filling it with extra cars and charge stations? Maybe. And there will surely be battery technologies coming down the line that will deliver huge range at low cost, which will just about kill the economic incentive for this sort of thing altogether.

But it's nice to think about how things might work in a more energy-efficient way that might get better usage out of each car on the grid, and use the entire traffic system as a single enormous battery dedicated to getting every vehicle where it needs to go rather than as a series of separate machines that each only look after themselves.

Source: University of Florida via IEEE Spectrum