If you’re going to kill animals for food, don’t waste their parts – that’s just rude. Use everything, snout-to-tail, and not just bones for glue or stomachs for drink-bags, either. Get creative!

So if Futurama’s Bender had his hands amputated, you could improvise replacements after a single trip to Red Lobster. Don’t believe me? Check out the following creepily hilarious video of lobster tail shells turned into robot “fingers.” They definitely work better than Jamie Lee Curtis’s hot dog fingers did in Everything Everywhere All At Once. And robots can even swim with them!

And why not? Crustacean shells are strong and flexible, renewably sourced, and so beautiful that designers at Apple should take notes. Countless industrial designers are inspired by biomimicry, but they use plastic, metal, and composites to create components shaped like biological structures, rather than using those actual structures in their mechanisms.

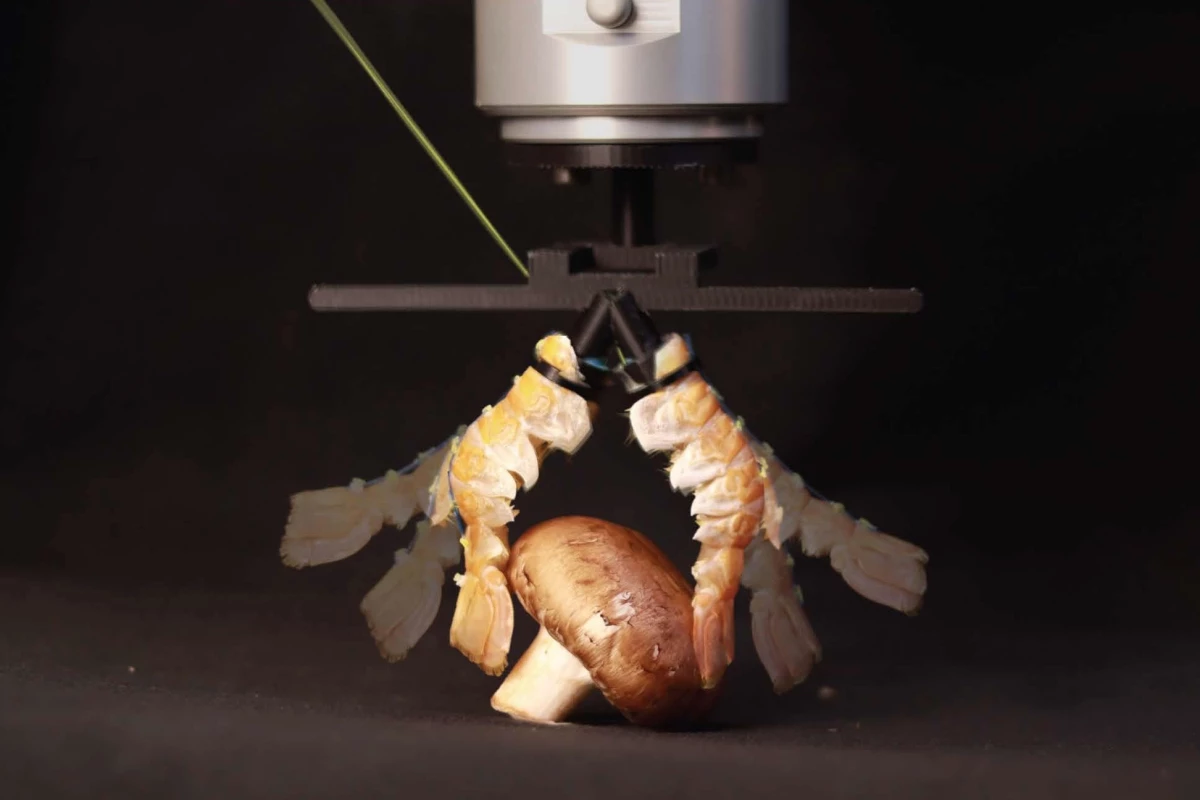

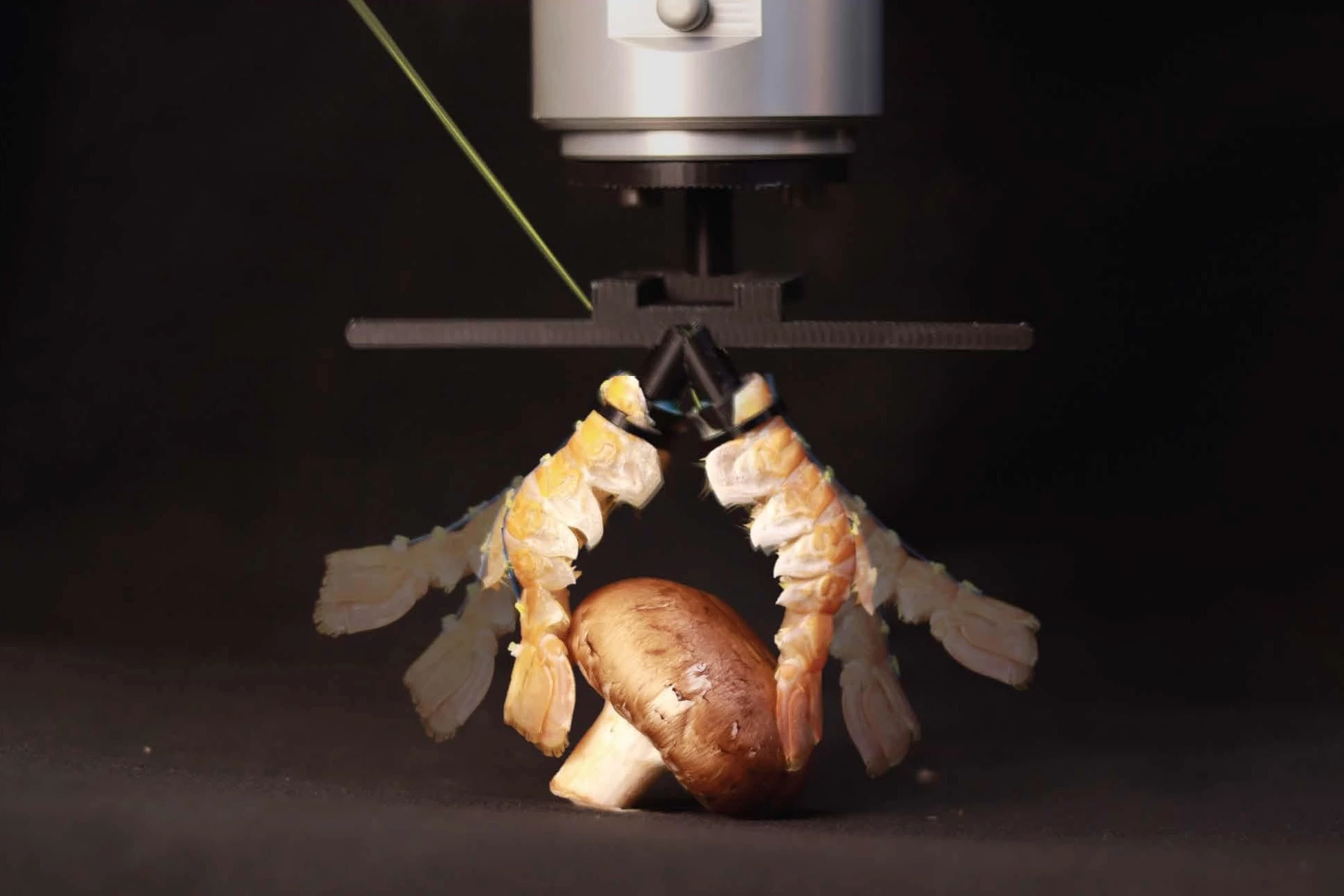

That’s why the new lobster tail design is so innovative. The experimental gripper from the Computational Robot Design and Fabrication Lab (CREATE Lab) at the School of Engineering in Switzerland’s École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) uses a pair of lobster tails as twin fingers, as discussed in an Advanced Science paper with the superbly sinister sea-punk-sounding title “Dead Matter, Living Machines: Repurposing Crustaceans' Abdomen Exoskeleton for Bio-Hybrid Robots.” Because it uses actual animal tissue, this “hand” isn’t bio-mimicked. It’s bio-derived.

“Exoskeletons combine mineralized shells with joint membranes,” says co-author Josie Hughes, head of CREATE Lab, which means they offer “a balance of rigidity and flexibility that allows their segments to move independently. These features enable crustaceans’ rapid, high-torque movements in water, but they can also be very useful for robotics. And by repurposing food waste, we propose a sustainable cyclic design process in which materials can be recycled and adapted for new tasks.”

Hughes’ point about food waste (an enormous problem which New Atlas has covered in numerous articles) is more than simply food for thought. As United Nations Climate Change reports, food waste (which was 1.05 billion tons in 2022) is responsible for 8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions – and costs the planet a trillion dollars – every year. Any repurposing of biowaste for good use decreases the generation of methane from anaerobic degradation in landfills (a disaster that the US Environmental Protection Agency nimbly explains in this guide).

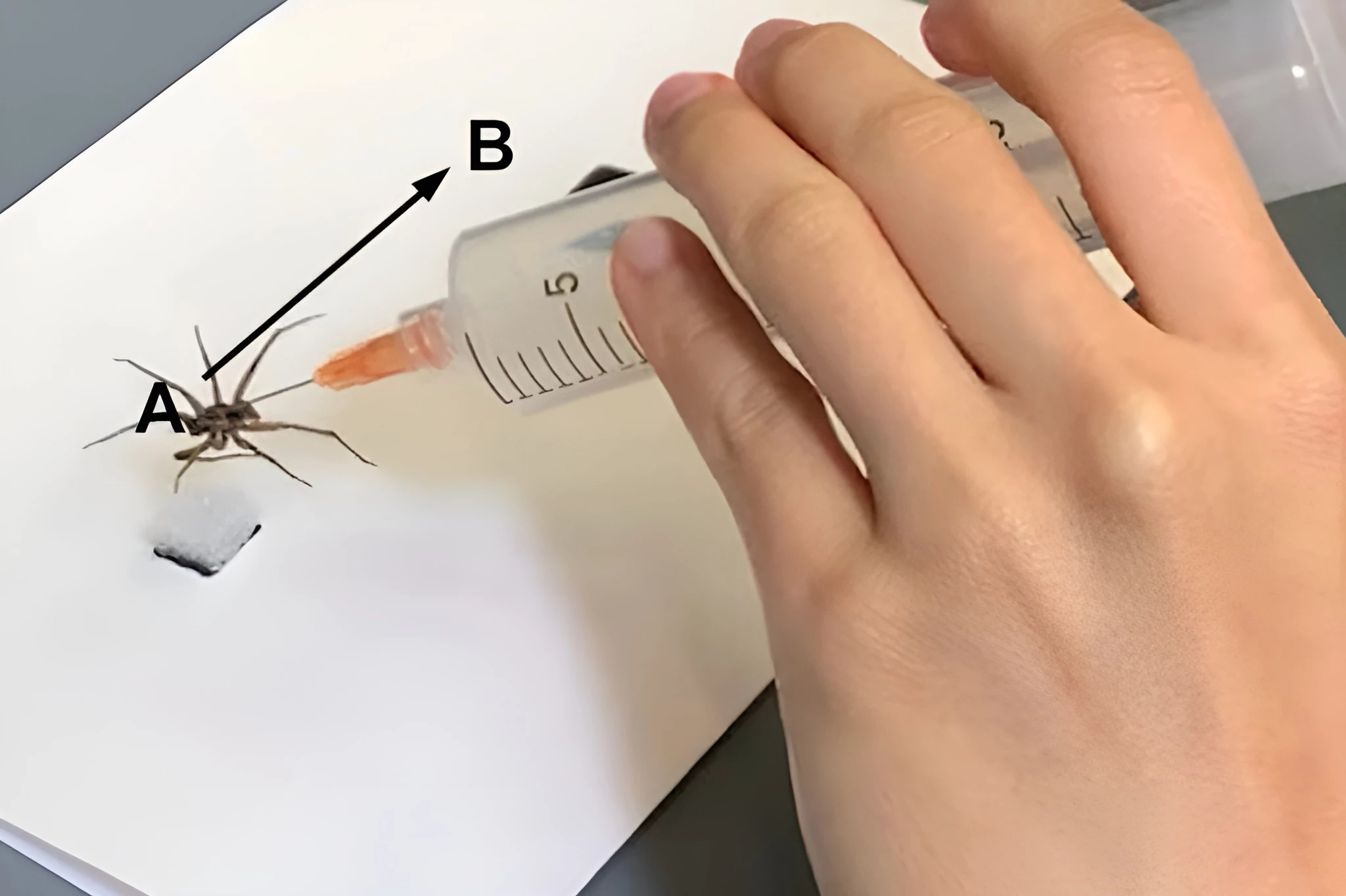

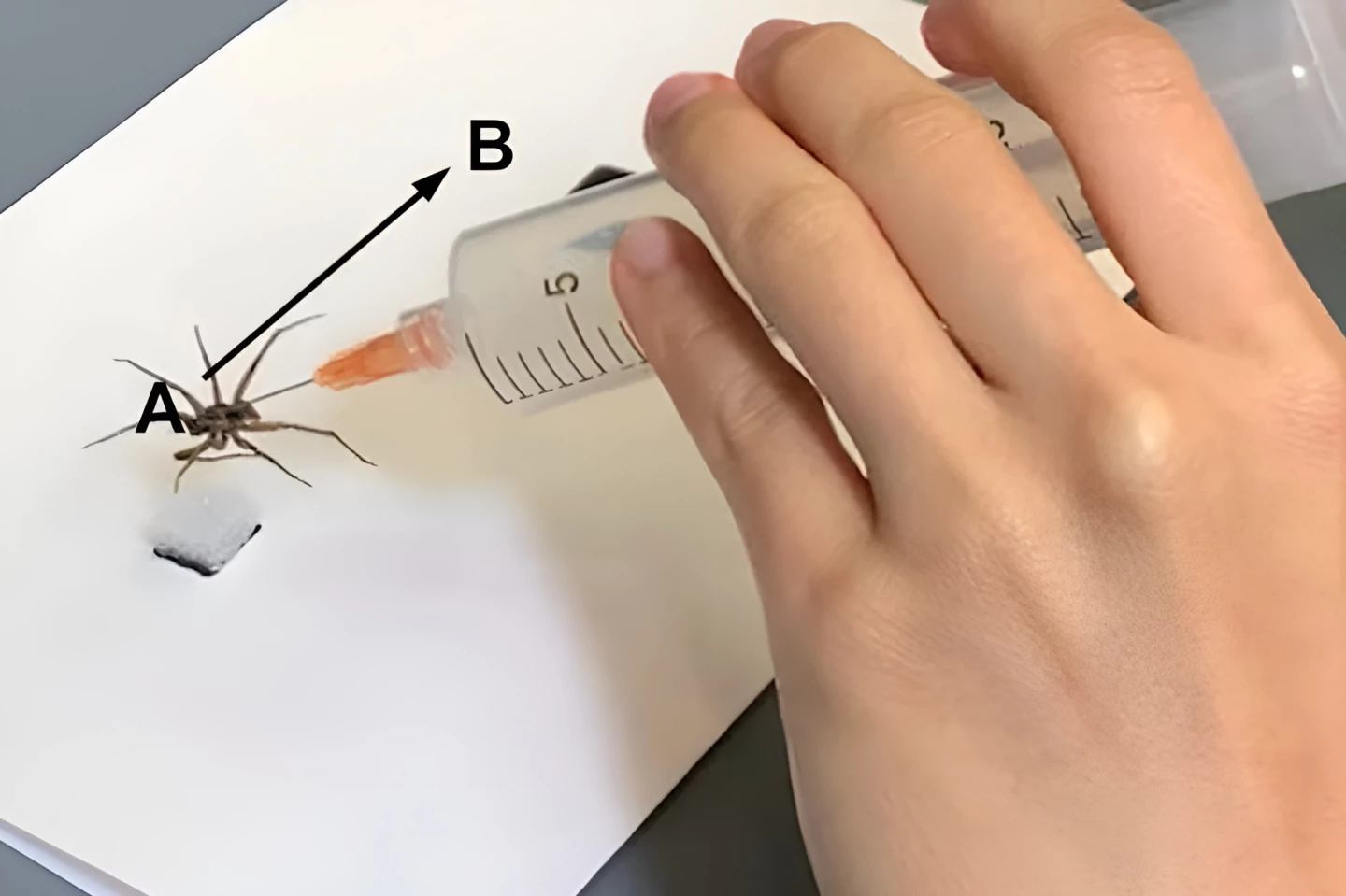

This isn't the first time scientists have used parts from dead animals for mech-hands. New Atlas reported on spider-based “necrobotic grippers” from Texas’ Rice University (which because of their size would actually make a great utensil for eating rice). But with a lifting capacity of 500 g (1.1 lb), the lobster-fingers could heft a dinner of steak and lobster.

They’re also supple enough to grasp objects of various sizes and shapes (including highlighter pens and tomatoes) without crushing them, thanks to an embedded, segment-controlling elastomer that, mounted on its motorized base, flexes and extends the “fingers.” With a reinforcing silicone coating to ensure longevity, the tails are ready for action – even (no surprise, given their source) as parts for robots that swim at up to 11 cm (about 4 inches) per second.

Best of all, following use, recyclers can separate the lobster and robotic parts and keep the synthetic components for other purposes. “To our knowledge,” says CREATE Lab researcher and the paper’s lead author Sareum Kim, “we are the first to propose a proof-of-concept to integrate food waste into a robotic system that combines sustainable design with reuse and recycling.”

Of course, unlike factory parts, lobster tails aren’t standardized, and instead grow in a variety of dimensions which bend differently, and so the researchers explain that future designs will require tunable controllers and other advanced synthetic augmentation mechanisms. If such innovations are successful, bio-derived devices could serve as implants and monitoring platforms.

As team lead Hughs says, nature “still outperforms many artificial systems and offers valuable insights for designing functional machines based on elegant principles.”

Source: EPFL