They’re gorgeous, dazzling, passionately pursued, and worth billions.

No, not Hollywood starlets and hunks and the stars of K-Pop. Well, OK, yes – they are gorgeous, dazzling, passionately pursued, and worth billions – but they’re nowhere near as useful to the world as rare earth elements (REEs). And thanks to bioengineering professor Seung-Wuk Lee and his team at UC Berkeley, there’s a brand new way to make viruses that can extract REEs without causing horrific, ecosystem-killing pollution and destruction. (No word yet whether the virus can do the same for starlets, hunks, and pop-stars).

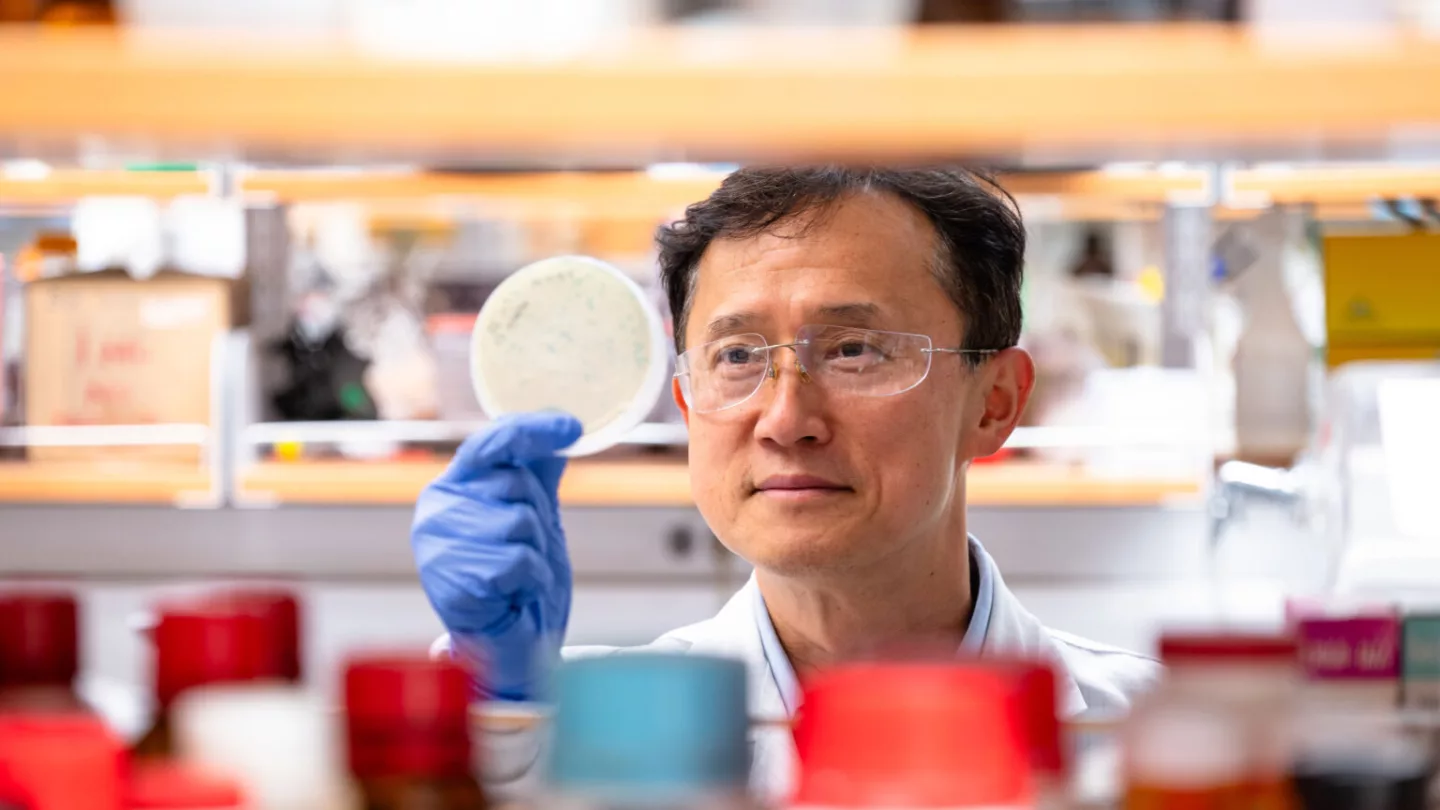

In a paper recently published in the journal Nano Letters, Lee and his team describe genetically engineering a harmless virus that acts like a microscopic aquatic miner by retrieving REEs from mine drainage water, and following a temperature and pH change, delivers them for harvest. Such a method could mean an eventual replacement of the pervasive and hyper-destructive methods of modern mining.

“This is a significant move toward more sustainable mining and resource recovery,” said principal investigator Seung-Wuk Lee, who is also faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Our biological solution offers a greener, low-cost, and recyclable way to secure the critical materials we need for a clean energy future while helping to protect the environment.”

Any country with REE reserves deploying such technology domestically would reduce its reliance on international sources of REEs, thus increasing its economic, industrial, and political independence. Currently, no country produces more REEs than does China, mining an estimated 240,000 tons of REEs and refining 189,179 tons in 2023. That’s 70% of the world’s REE mining and 87% of its REE refining.

In their various states of oxidation, the shiny, metallic REEs can form a range of colorful compounds. While precious, the REEs aren’t exactly atomic celebrities sipping martinis and eating caviar around a glamorous periodic table. So, forget the attention-getting elements such as gold, iron, and platinum, and fix your eyes instead on this substantial crew of exotic refinement: the two transition metals scandium and yttrium, and the 15 lanthanides including promethium, europium, and gadolinium.

So, how does the virus work? Lee’s team transformed a bacteriophage (a type of virus that attacks bacteria without harming humans or the rest of the biosphere) into a micro-mining machine by adding two specialized proteins. One is a lanthanide-binding peptide on the phage’s surface acting as a claw for collecting REEs, and the other, an elastin motif peptide that, when temperature-activated, exits the solution and delivers its REEs.

For an outstanding bonus, the biomining viruses remain effective even after completing their “shift,” meaning they can come back to work whenever they’re needed. They’re easy and inexpensive to grow at industrial scale, too – simply add them to bacteria, and when the bacteria replicate, the virus replicates with them.

According to Lee, the new biomining method is “not only eco-friendly, but also incredibly simple, requiring little more than a mixing tank and a heater.” With it, scientists “can use a programmable, biological tool to perform a complex industrial task that currently requires toxic chemicals and a lot of energy.”

Because of REEs’ ability to enhance miniaturization, efficiency, durability, and performance, the world craves them. Used in consumer electronics such as mobile phones, computers, televisions and monitors, LEDs, camera lenses, fluorescent lights, REEs are also indispensable for countless industrial applications including glass-colourants, lasers, weaponry, MRIs, catalytic converters, polishing powders used in semiconductor manufacturing, fuel cells, rechargeable batteries, and vehicles for land, air, and space.

REEs’ most widespread function in 2023 – about 45%, as the Government of Canada reports – is the manufacture of permanent magnets which make wind turbines and EVs (and the vibrating magnet in your cellphone) possible.