Scientists in Australia have demonstrated that clusters of brain cells in a lab dish can be taught to play Pong in an approximation of sentience. This is the first time that these cells have shown the ability to perform goal-directed tasks, and it opens the door for new understandings of the brain.

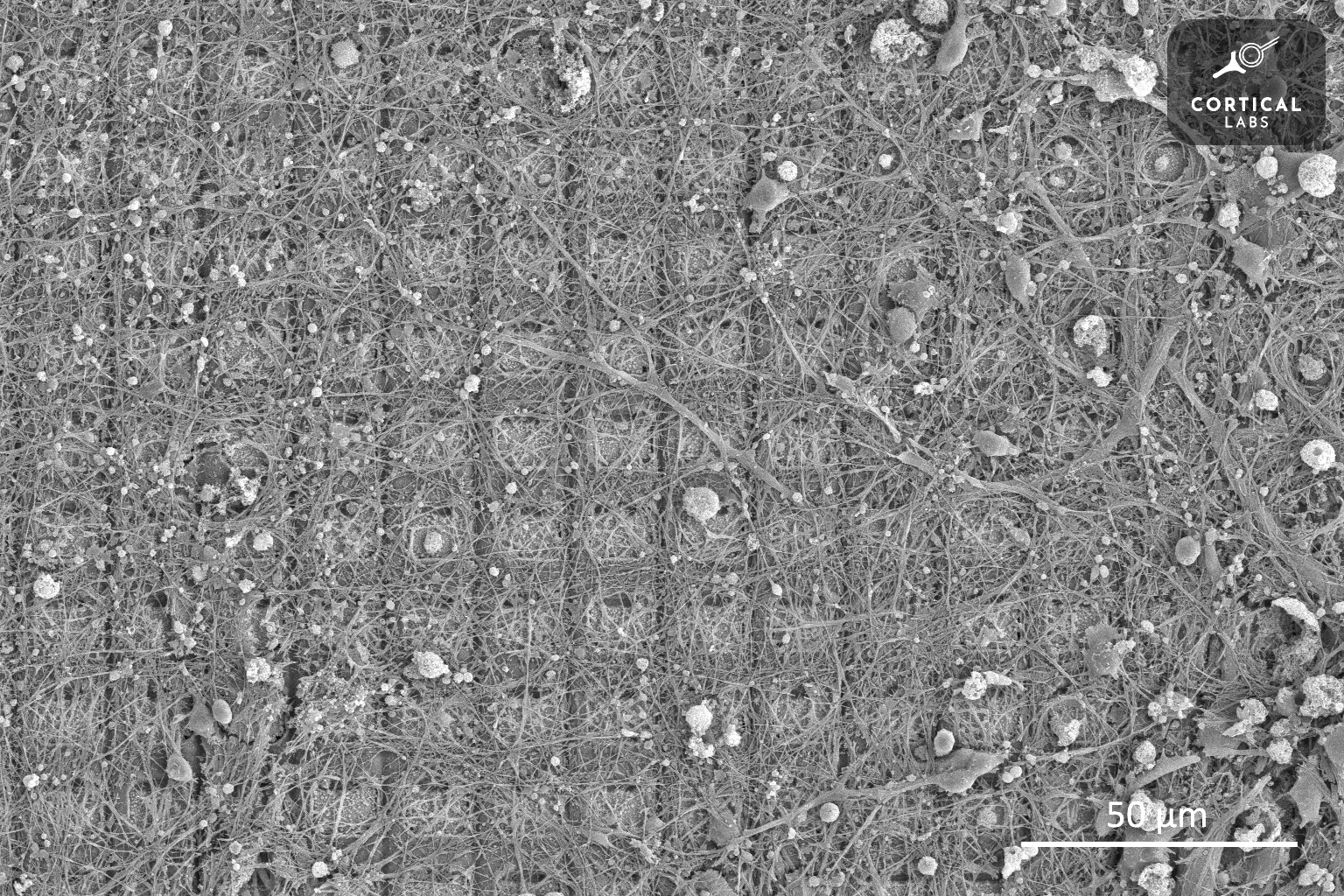

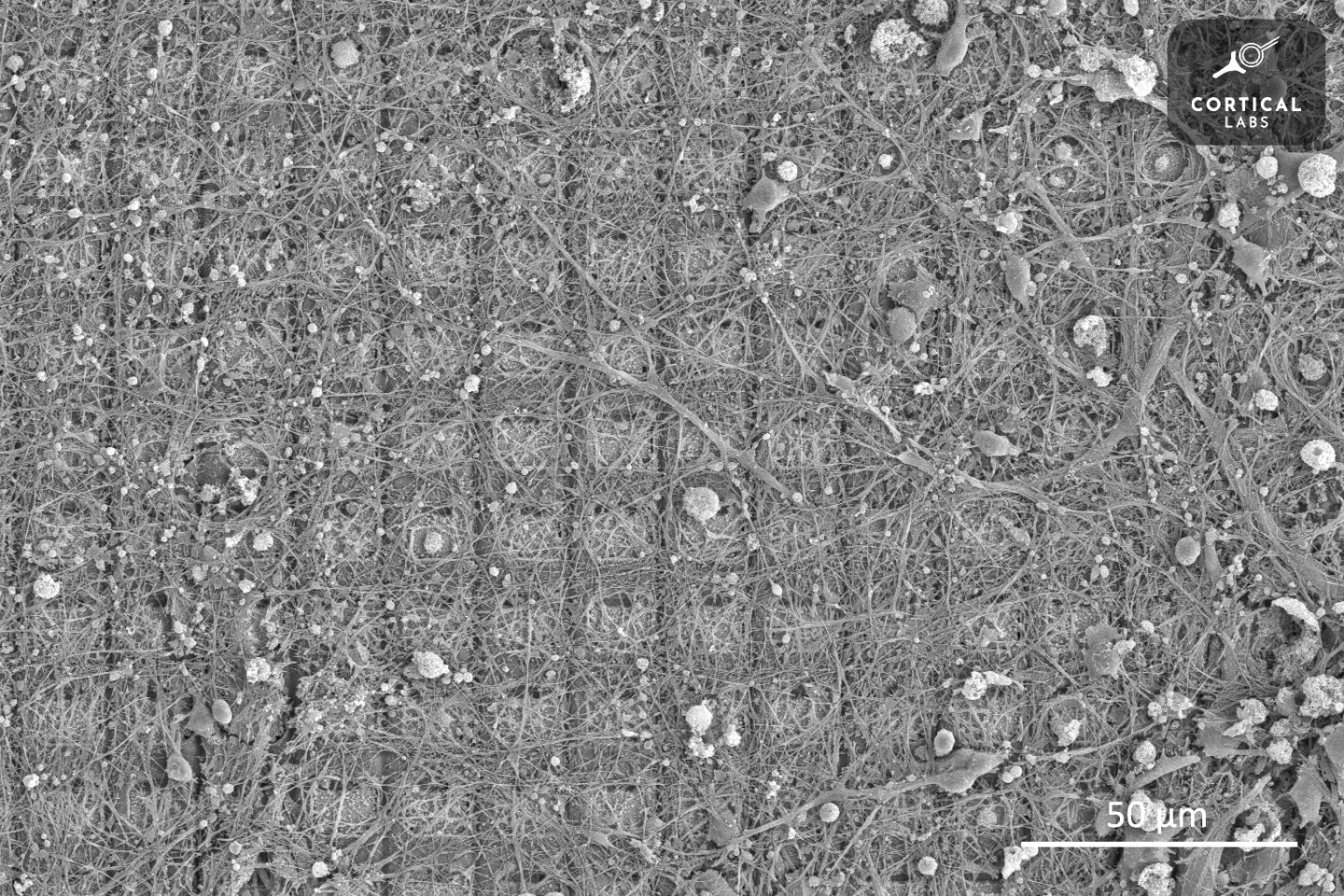

The system, which the team calls “DishBrain,” is more or less exactly what it sounds like – 800,000 human and mouse neurons grown in culture and mounted on arrays of microelectrodes that can read their activity and stimulate them with electrical signals. In previous work, these kinds of setups have been used to study neurological development and disease, but this is the first time these lab-grown brains have been taught to perform a specific task.

The team effectively placed the brain cells in a virtual recreation of the classic arcade game Pong, where the cells themselves acted like the paddle and had to bounce a simulated ball away in time. Electrodes on either side of DishBrain would fire to indicate the location of the ball at any given time, while the frequency of the signals would increase or decrease to indicate the ball’s distance from the paddle. The neurons had to send their signals around to move the virtual paddle and hit the ball.

“This new capacity to teach cell cultures to perform a task in which they exhibit sentience – by controlling the paddle to return the ball via sensing – opens up new discovery possibilities which will have far-reaching consequences for technology, health, and society,” said Dr Adeel Razi, co-author of the study.

Training DishBrain was understandably tricky. Reward and punishment are usually key if you’re going to train an organism to perform a specific task, but that won’t work on these cell cultures because they have no dopamine system to incentivize them. Instead, the researchers took advantage of what’s called the free energy principle.

Essentially, this idea says that cells at this level will always try to minimize the unpredictability in their environment. So, if the brain cells failed to hit the ball with their paddle, the system would deliver an unpredictable stimulus for four seconds, but for every successful hit they would receive a brief, predictable signal before the game continued on, also in a predictable manner. Using this, DishBrain learned to play the game within five minutes.

“The beautiful and pioneering aspect of this work rests on equipping the neurons with sensations – the feedback – and crucially the ability to act on their world,” said Professor Karl Friston, co-author of the study. “Remarkably, the cultures learned how to make their world more predictable by acting upon it. This is remarkable because you cannot teach this kind of self-organization; simply because – unlike a pet – these mini brains have no sense of reward and punishment.”

This experiment may sound a bit spooky and ethically questionable, but other scientists explain that it isn’t a kind of intelligence that we need to worry about mistreating.

“Don’t worry, while these dishes of neurons can change their responses based on stimulation, they are not sci-fi style intelligence in a dish, these are simple (albeit interesting and scientifically important) circuit responses,” said Professor Tara Spires-Jones, UK Dementia Research Institute Programme Lead.

The researchers on the study say that the new work can help improve our understanding of the human brain, using a more accurate model than computer simulations. The next steps are to investigate the effects of drugs and alcohol on the neurons, including whether they impair the cells’ ability to play the game.

The research was published in the journal Neuron.

Source: Monash University via Scimex