We all learned in elementary school science that water freezes at 0 °C (32 °F) – but it’s actually not quite that simple. New experiments from the University of Houston have shown that tiny droplets can remain liquid right down to -44 °C (-47.2 °F), if kept in contact with a soft surface.

The freezing point of water isn’t a hard-and-fast line – it’s more of a starting point where water molecules will begin to freeze. The first ones to switch are those exposed to cold air at the surface, and the ice crystals they form trigger neighboring molecules to freeze too. This process continues until the entire body of water becomes ice.

For any given water droplet, it will freeze somewhere between 0 °C and -38 °C (-36.4 °F). But for the new study, the researchers managed to keep some particularly tiny droplets in their liquid form at temperatures as cold as -44 °C.

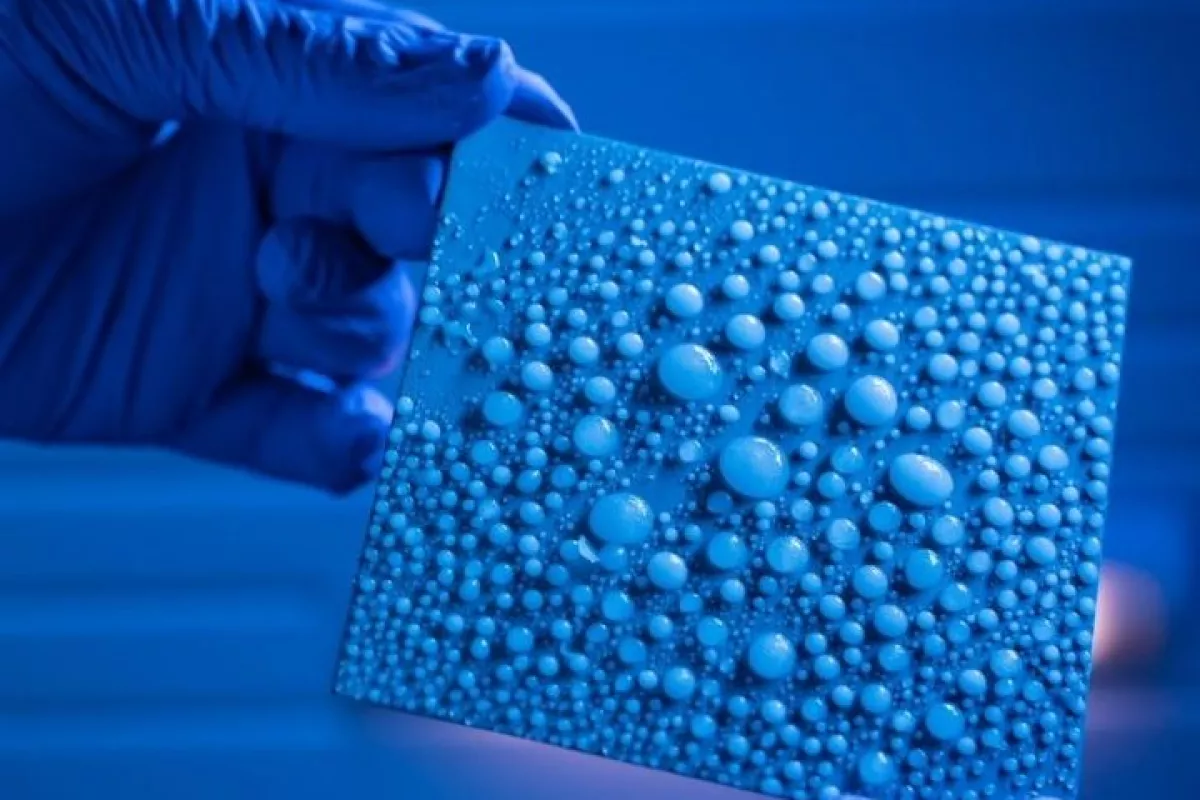

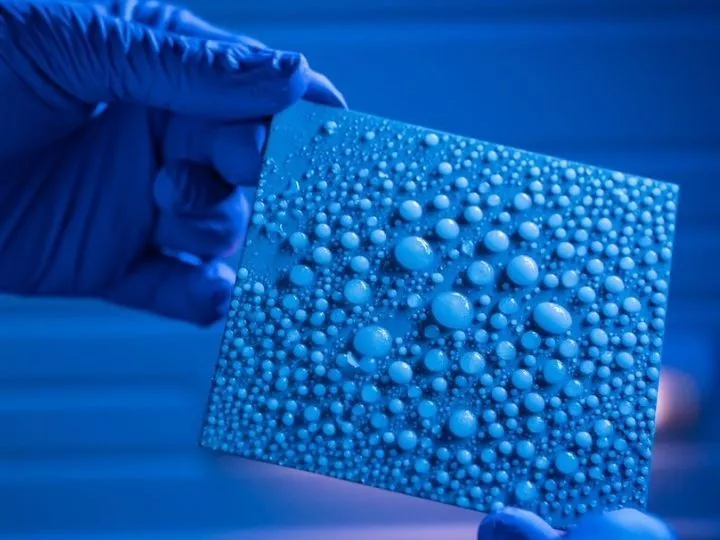

The key, according to the team, is the type of surface that the water is in contact with. Ice crystals form easily on hard surfaces, but softer interfaces, like oils or gels, can suppress that formation for longer. And smaller droplets could stay liquid for even longer than larger ones.

To peer closer at the physics of the water-to-ice transition, the team was experimenting with water droplets just two nanometers across, compared to the usual range of about 100 nm. To do so, the researchers confined water to the pores of a membrane made of anodized aluminum oxide. The nanodroplets were surrounded by octane oil to keep the interface “soft.”

“Experimental probing of freezing temperature of few nanometer water droplets has been an unresolved challenge,” says Hadi Ghasemi, corresponding author of the study. “Here, through newly developed metrologies, we have been able to probe freezing of water droplets from micron scale down to 2 nm scale.”

The team says that the find could help develop new methods to reduce ice formation on the surfaces of aircraft, wind turbines and other infrastructure. It could also lead to improved cryopreservation systems for food or tissues that don’t damage cells through ice crystal formation.

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Houston