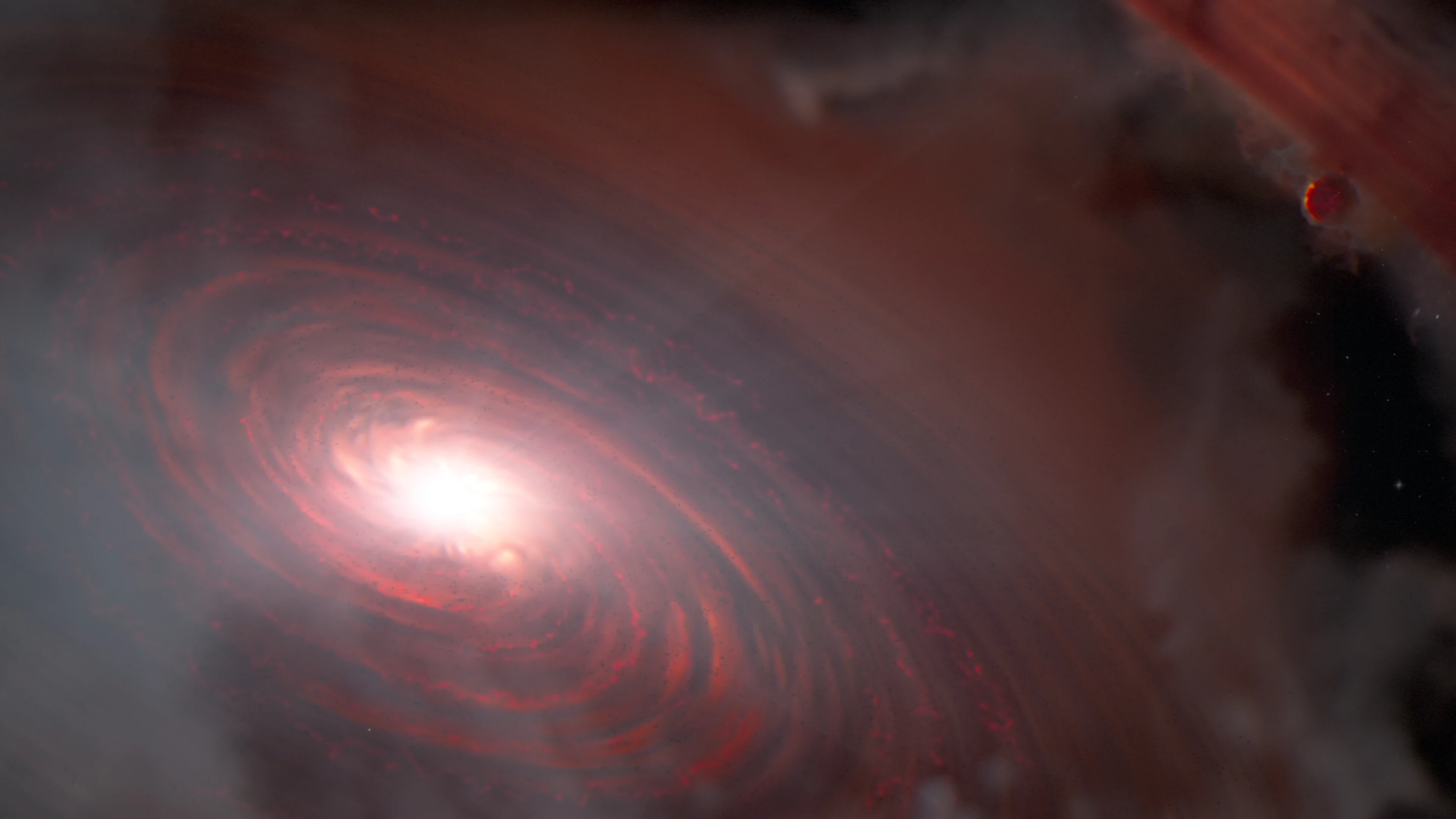

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope has scored another first, detecting evidence of water in a planet-forming disc circling another star where at least two terrestrial-class proto-planets seem to be forming.

The more scientists learn about the universe, the more questions are raised, which can be slightly annoying. Two mysteries that have come up in recent years are, how many Earth-like planets are there in the galaxy where life might exist, and the related problem of how the Earth got its water billions of years ago.

Part of the answer to both of these may come from the system of PDS 70, which is a very young dwarf star located 370 light years away in the constellation of Centaurus. It's already been in the news lately because the planet-forming disc of dust and debris circling within 160 million km (100 million miles) of the star is home to what may be two proto-planets that share the same orbit.

That's already sensational enough, but the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) instrument aboard the James Webb found something else in this region where rocky terrestrial planets form. PDS 70 is estimated to be only about 5.4 million years old with inner and outer planet-forming discs, the outer being home to a pair of Exo-Jupiters.

In the inner disc MIRI found dust combined with the infrared signature of water vapor. This may be in the form of water molecules that are forming out of atoms of hydrogen and oxygen, or it may be ice particles that have migrated in from the colder outer disc.

Whichever it is, the surprise is not only the presence of water, but also how it survives in the intense ultraviolet radiation from the dwarf star. The most likely explanation is that it is shielded by dust or other water molecules.

However, the big takeaway is that this discovery may provide scientists with a clearer explanation of how water appears on terrestrial planets. This will not only help to estimate the number and nature of potentially habitable planets in our galaxy, but may also help resolve the question of how Earth came to be so wet. Was it due to comets and asteroids colliding with the young Earth? Was the water already in its interior as it formed? Or was it a combination of the two?

"We’ve seen water in other discs, but not so close in and in a system where planets are currently assembling," said lead scientist Giulia Perotti of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany. "We couldn’t make this type of measurement before Webb."

The research was published in Nature.

Source: ESA