For roughly a decade, Microsoft has been perfecting a high-density storage technology that uses glass, lasers, and cameras, and ensures it stays intact for millennia. That's a huge improvement over existing magnetic tape and hard drives used for archiving data, which are good for only up to a decade at the most.

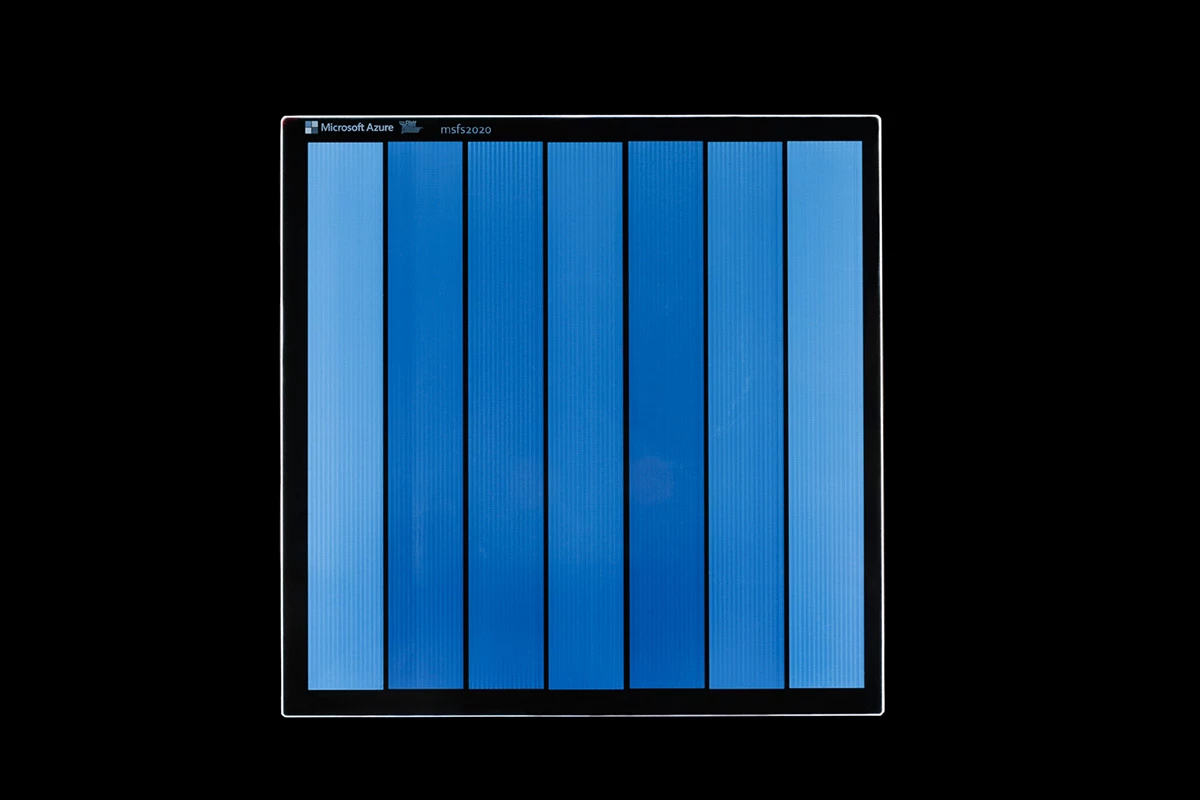

It's called Project Silica, and we've seen it demonstrated a couple of times: holding the 1978 movie Superman on a coaster-sized slide of silica glass in 2019, and with its capacity expanded a hundredfold, from some 75 GB to more than 7 TB in 2023.

The company says it's now made a major breakthrough on the material front. Rather than relying on expensive fused silica glass, its updated encoding method works with ordinary, low-cost borosilicate glass – the same kind that's used in cookware.

That should make the technology far easier to adopt, especially when you consider the sort of applications it could be used for: medical, industrial, and scientific data, archiving the web, datasets for AI, and media libraries from giant publishers of film, music, and literature.

How does Project Silica work?

The tech uses tough glass that's resistant to water, temperature changes, and magnetic interference, which would destroy a normal computer hard drive. Instead of using magnets or chemicals that can fade, a very fast laser (called a femtosecond laser) is used to create tiny, permanent marks deep inside the glass.

These marks are called voxels, which you can think of as 3D pixels. The laser actually changes the physical structure of the glass, so the encoded data is locked in and cannot be easily erased or altered once it is written.

Project Silica writes data in hundreds of layers throughout the entire 2-mm thickness of the glass.

To see how long the data remains intact without actually standing around, scientists at Microsoft use accelerated ageing tests, in which they "bake" the glass at extremely high temperatures to simulate the passing of thousands of years. They found the data remained stable even at 554 °F (290 °C), meaning it will last well over 10,000 years at normal room temperatures.

Lastly, the system uses machine learning to read the voxels back. Even if there are tiny imperfections in the glass or the writing process, the system uses what's known as forward error correction to fill in the gaps and ensure the information is retrieved exactly as it was saved.

What's new with Project Silica?

The team had already achieved all this in previous years. In a paper that appeared in Nature this week, the Project Silica researchers noted they could switch from the fused silica medium to potentially any transparent media, like durable borosilicate glass. With the latest iteration of this tech, the team found that a 120-mm (4.7-in) square piece of glass can store just over 2 TB of data with a write speed of 18.4 Mbits.

This was made possible thanks to a new method of 'marking' the glass to store information – going from birefringent voxels that require a two-step process to create microscopic needle-like structures in the glass, to phase voxels that allow for faster reading and writing with simpler hardware.

The old method encoded data by changing how glass interacts with polarized light. The new "phase voxel" method works differently – it slightly changes the physical structure of the glass itself, which alters how light waves travel through it. The big win here is that it only takes a single laser pulse to create one of these dots, making it simpler and cheaper. The downside is that nearby dots interfere with each other more, but the team solved that using a machine learning model to decode the data accurately.

Those of you reading closely will have noticed the lower storage capacity with this method. That's the trade-off with phase voxels, but it comes with the upside of using simpler reading and writing hardware.

And rather than writing one data dot at a time, the scientists developed a system that splits the laser beam to write many dots simultaneously. They also used the tiny flashes of light that occur as a side effect of writing to automatically calibrate and control the process in real time.

With that, Microsoft is inching far closer to a long-term data storage system we might find use for in the near future than some other promising technologies. That includes tiny high-capacity storage drives which use a new type of magnetic module, and hard disk drives that use 'P-wave magnetism,' an entirely new form of the force in a synthesized crystalline material.

There are plenty of considerations that would go into building out this tech for real-world usage, including the cost of writing and retrieving stored data, and the systems needed to efficiently find what you're looking for among zettabytes stashed in small pieces of glass.

Source: Microsoft