No, not that Turing test – although there's probably a little self-aware humor going on here. The Facebook/Meta CEO is laser-focused on creating VR headsets that deliver visual experiences that are indistinguishable from reality, and the company has taken the unusual step of revealing a slew of prototypes to outline the monolithic challenge this entails.

Meta is already at the forefront of VR. Its Oculus Quest 2 headset is far and away the most complete, intuitive and tightly integrated product in the space. It might not be capable of running the most graphically hardcore VR titles yet, but it's a fully self-contained unit that's comfortable to wear and doesn't need to be plugged into anything to deliver a broad range of immersive VR experiences.

The sheer power and smarts of the Quest 2 are absolutely stunning for a consumer device at the price it sells for, but Meta won't be happy until you can't tell the difference between the real world and the virtual world. In the company's latest "Inside the Lab" roundtable, Zuckerberg and senior team members detailed the technological gaps between the Quest 2 and a future device that'll be capable of passing a "visual Turing test" and completely fooling your visual cortex. And they showed off a range of prototypes, each designed to push toward a particular solution.

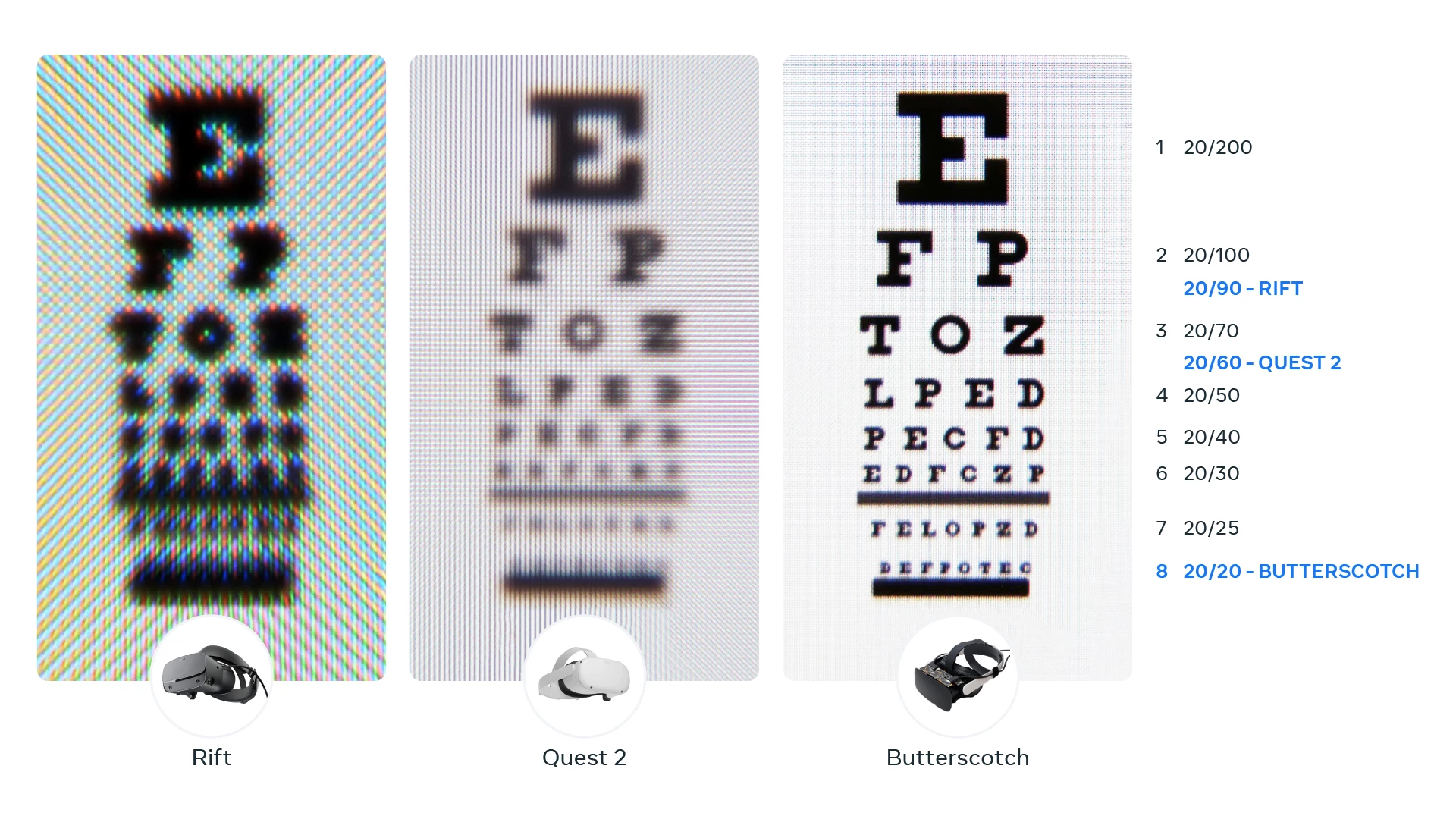

Retinal resolution and the Butterscotch prototype

The human eye at 20/20 vision, says Meta, can distinguish about 60 pixels per degree of field of view. Easy enough for a high-def TV screen, especially one that you're sitting a good distance back from. But VR goggles are right up in front of your eyes, so pixels need to be absolutely tiny, and they also need to cover your entire field of vision – something that's never required of a TV screen. Meta's target resolution is more than 8K for each eye.

The company built its "Butterscotch" prototype to test the effect of super-high resolution on the viewing experience. As you can see, it's massive, bulky and nowhere near production-ready. It can also only handle about half of the Quest 2's current field of view, which itself feels a bit cramped around the periphery. But it delivers 55 pixels per degree of vision, about 2.5 times better than the Quest 2, and it's the best the company has managed thus far.

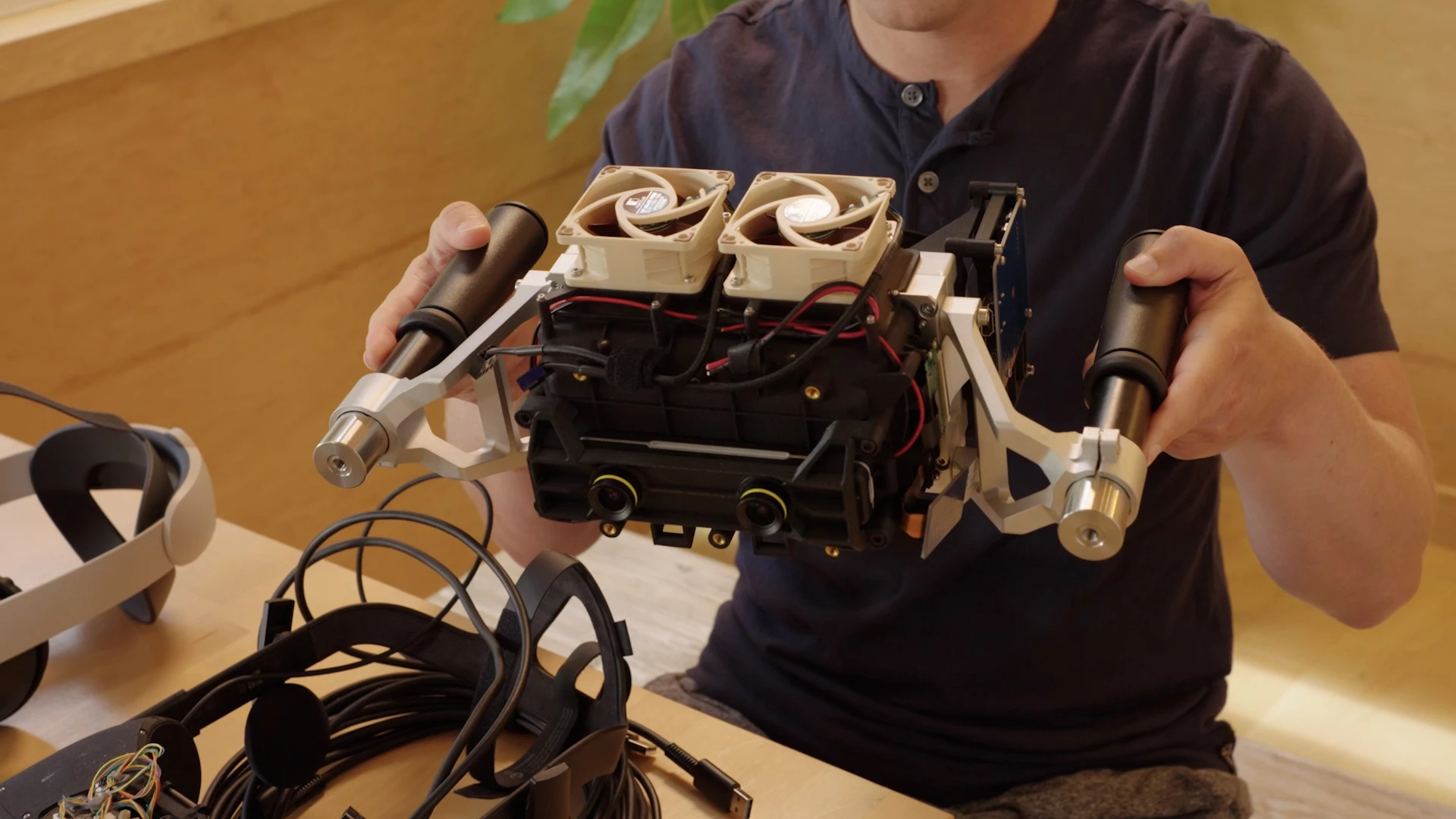

Dynamic range, peak brightness and the Starburst prototype

Every bit as important as resolution is a display's ability to push lots of photons and create a huge difference in brightness between the highlights and shadows in an image. In order for a scene to appear as bright as daylight and fool your visual systems, Meta wants to build a high dynamic range (HDR) display capable of more than 10,000 nits of peak brightness. For comparison, the Quest 2 can push a peak of 100 nits, so there's plenty of room for improvement.

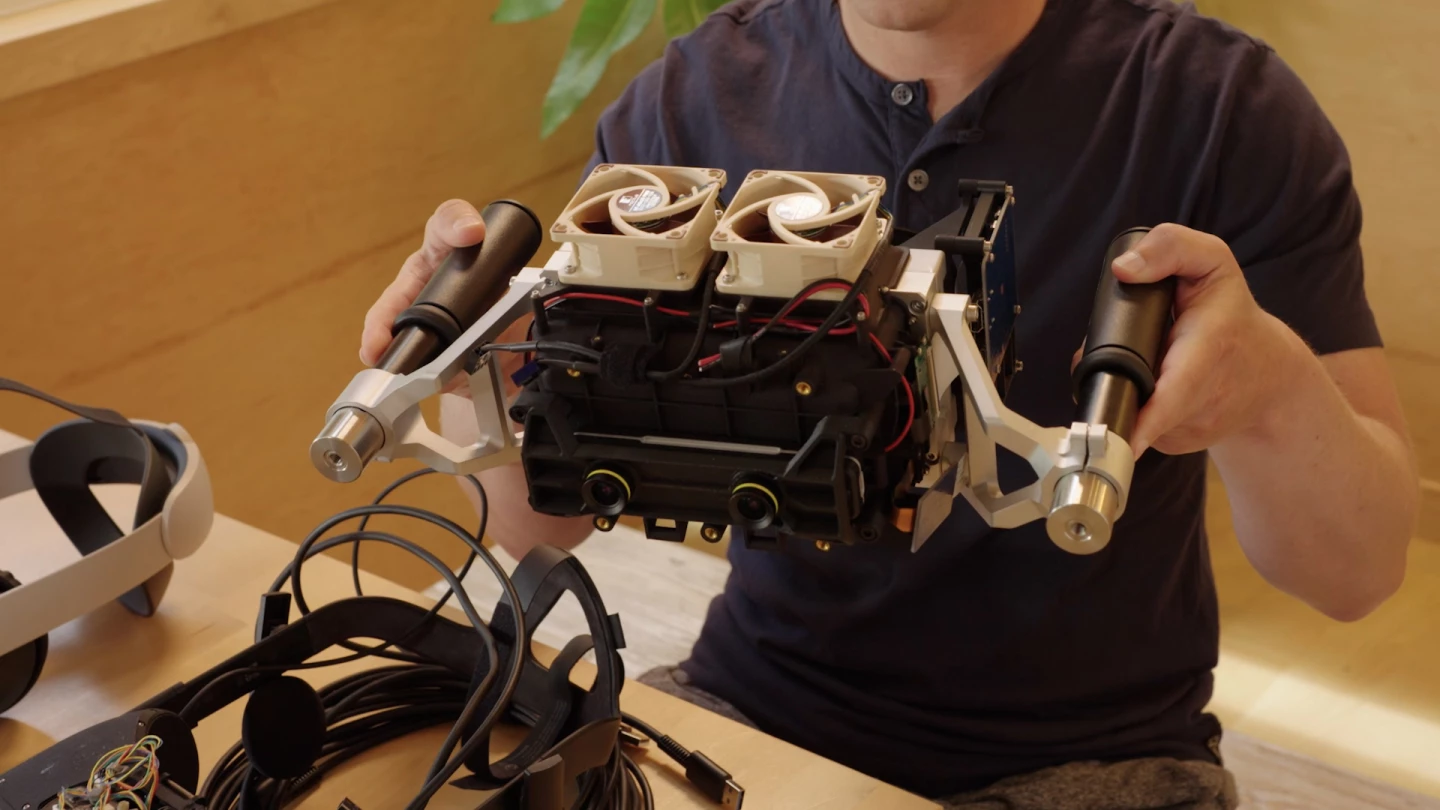

In order to get into the ballpark, Meta created the Starburst prototype, which, according to Zuckerberg, "basically puts an incredibly bright lamp behind the LCD panels." Starburst is super chunky – so big, indeed, that they put handles on it rather than a head strap – but it's one of the brightest HDR displays ever built, maxing out at 20,000 nits.

Varifocal imaging, distortion and the Half Moon prototypes

In the real world, things are different distances away, and as you look at them your eyes adjust their focus accordingly. "Our eyes are pretty remarkable," says Zuckerberg, "they pick up all kinds of subtle cues when it comes to depth and location. And when the distance between you and an object doesn't match the focusing distance, it can throw you off and be a bit uncomfortable. And your eyes try to focus and they can't quite get it right, which can be tiring and can lead to a little bit of blurring."

This is an insanely difficult thing to replicate in VR, because of course the screen stays a constant distance from your eyes. Up until this point, the Oculus headsets have set a single point of focus around 5-6 feet (1.6 -1.8 m) away, but Meta feels it's not going to pass a visual Turing test until it can deliver an image that exercises your eyes the way the real world does.

So Meta set about building a display system that would be able to dynamically change the focal point by mechanically moving a series of lenses as you look around a scene, causing your eyes to focus at the perfect distance to create a more realistic sense of presence. To do this, though, it needs to know exactly what you're looking at. So the Half Moon 0, 1 and 2 varifocal prototypes use eye-tracking to pinpoint where you're looking and set the focus accordingly, while also making real-time corrections to eliminate the image distortion that results when you change the focus.

The latest prototype, Half Dome 3, replaces the mechanical lens system with electronic liquid crystal lenses, making the whole thing much smaller. Testing appears to confirm that these varifocal systems do make the experience more realistic for people, but there's a way to go yet – in particular, the distortion-correction algorithms will need to change depending on eye direction, and it all needs to happen so fast that the human eye can't catch it.

On the positive side, with eye-tracking built in, the team can take some load off the graphics processing system. The human eye can see in exceptional detail in the center of your field of view, where the light falls upon the fovea, a small indentation in your retina where visual acuity is at its highest. But your eye's resolution drops right off going out toward your periphery. So if the system knows where you're looking, it can render a level of detail to suit human physiology, saving energy, heat and processing power by dropping detail around the periphery of your vision in a process known as foveated rendering.

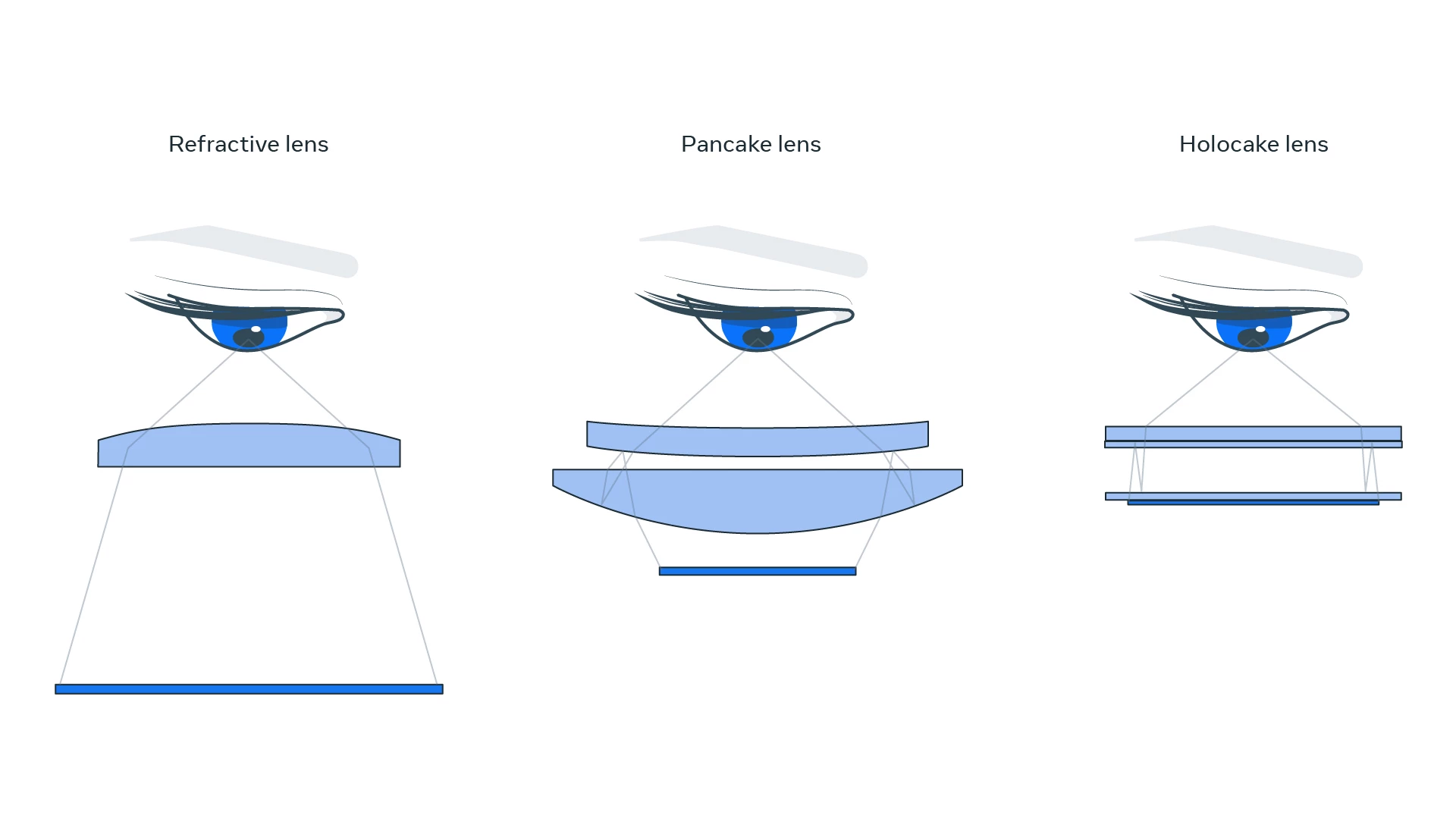

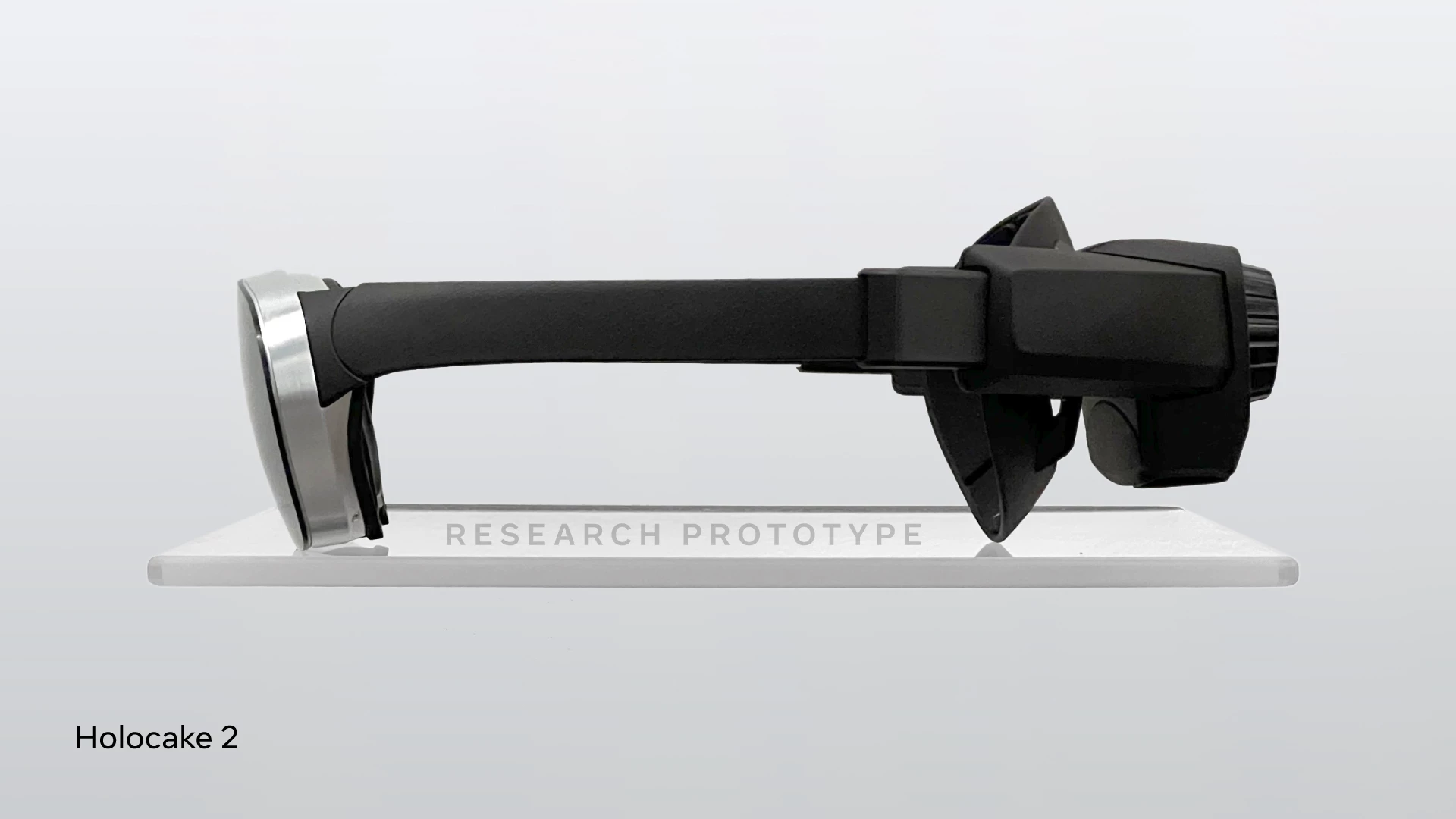

Miniaturization, holographic lenses and the Holocake prototype

Nobody's going to want to spend much time in VR with a brick strapped to their head. The Quest 2 isn't too annoying to wear, but Meta knows it's going to have to get a lot smaller, and it knows that'll be impossible using today's thick optical lenses. Indeed, if there's one thing that's responsible for today's front-heavy face-brick form factors over all else, it's the traditional optics. As a result, Meta has been working on holographic lenses.

"Instead of sending light through a lens, we send it through a holograph of a lens," says Zuckerberg. "And holographs are basically recordings of what happens when light hits something. So just like a holograph is much flatter than the thing itself, holographic optics are much flatter than the lenses that they model, but they affect incoming light in pretty much the same way. So it's a pretty neat hack."

He continues: "The second new technology is it uses polarized reflection to reduce the effect of distance between the display in the eye. So instead of going from the panel through a lens and then into the eye, light is polarized so it can be bounced back and forth between reflective surfaces multiple times. And that means that it can travel the same total distance, but in a much more compact package. So the result is this thinner and lighter prototype than any other configuration."

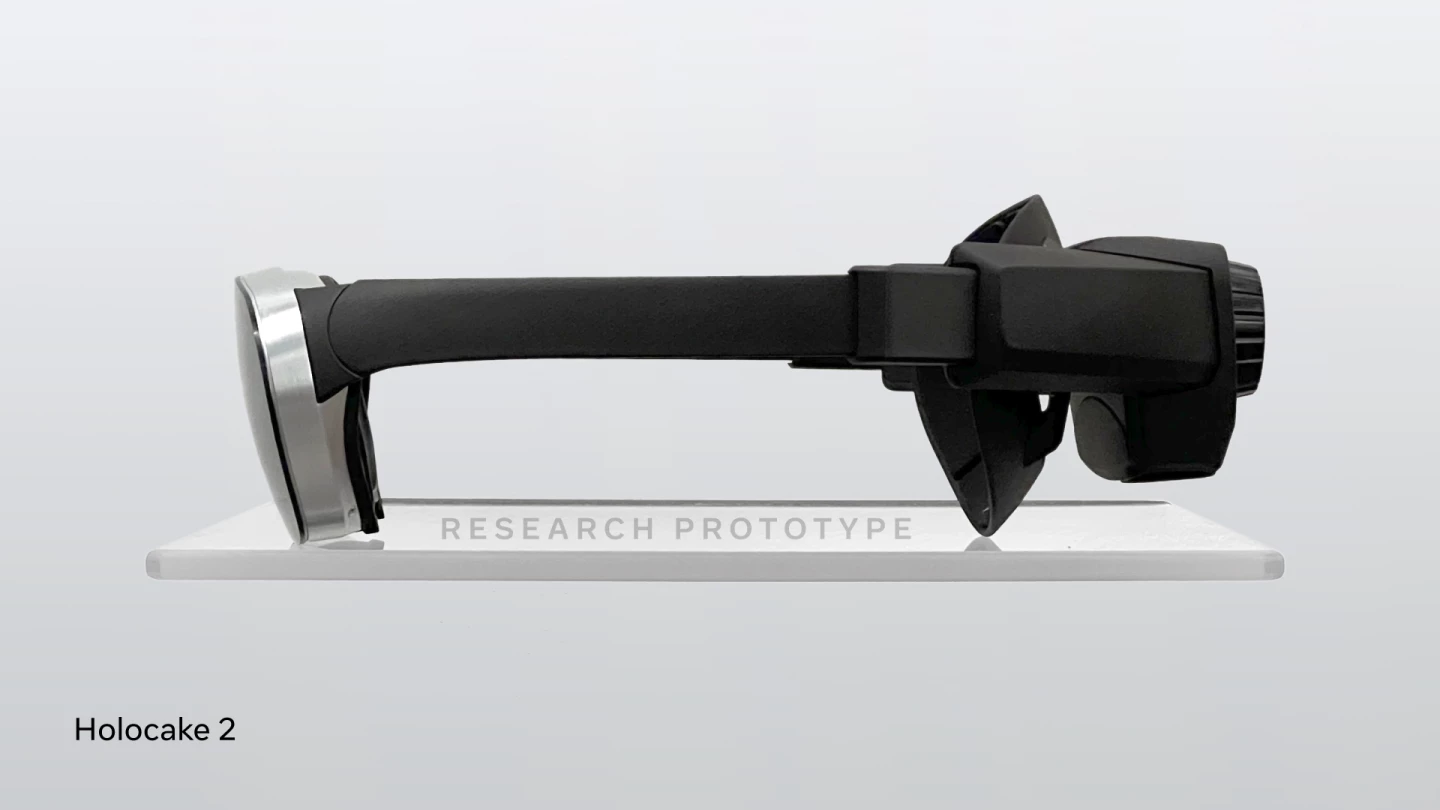

We're not going to pretend we understand optics at this level, but the Holocake 2 prototype goggles are extraordinarily compact. Zuckerberg says these things have around the same end-user performance specs as the Quest 2, but they're barely thicker than a set of Coke-bottle glasses, and don't cover much more of your face than a pair of oversized aviators.

The catch, according to Meta Reality Labs Chief Scientist Michael Abrash, is that in order to make the Holocake 2 prototype into a shippable product, Meta would need to find a specialized laser system that's safe, efficient and cheap enough to put in a consumer product. "As of today, the jury is still out on finding a suitable laser source," says Abrash, "but if that proves tractable, there will be a clear path to sunglasses-like VR displays."

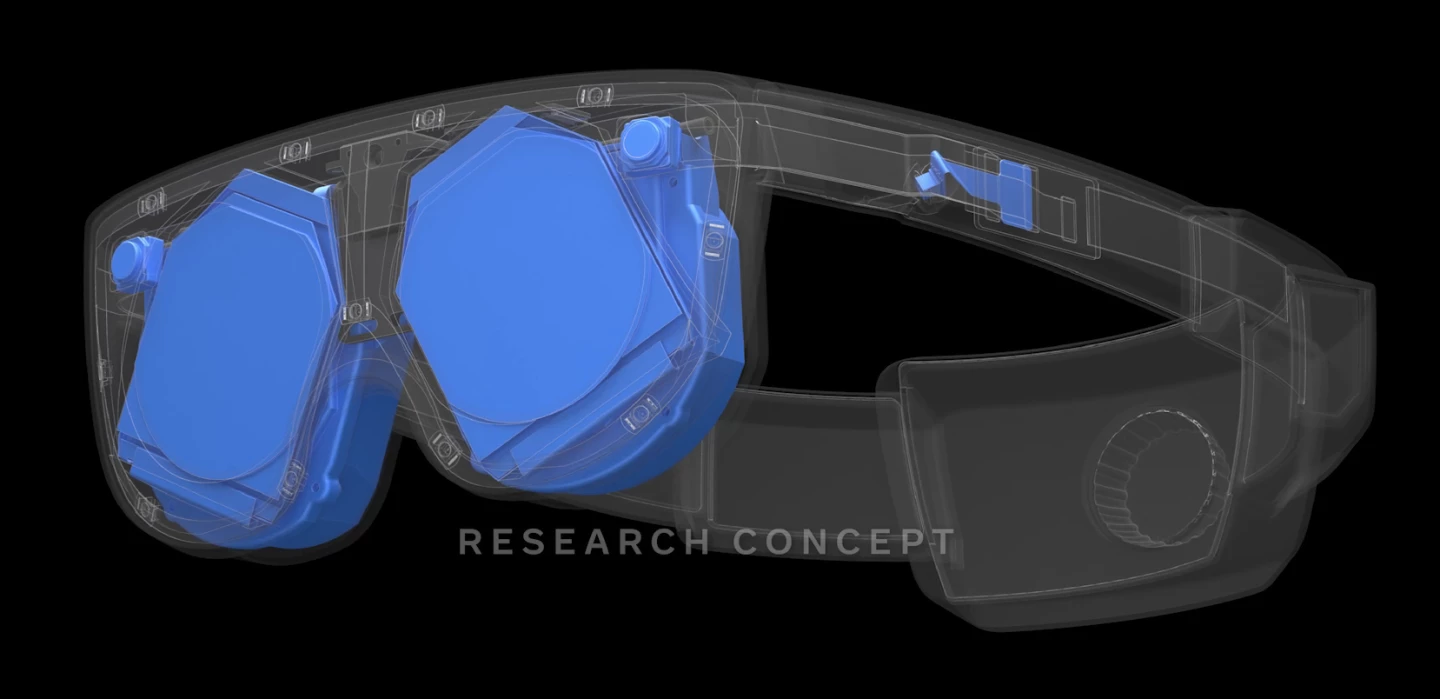

Putting it all together: the potentially upcoming Mirror Lake prototype

All of the above technology, rolled into a single device – one that also has all the onboard cameras and processing required to run this next-gen tech in a standalone headset, plus enough battery for extended sessions, in a form factor much smaller than anything that's currently on the market. That's the dream; that's the future.

The Mirror Lake prototype is a first cut at putting it all together. "Mirror Lake is a concept design," says Abrash, "with a ski goggles-like form factor that takes the Holocake 2 architecture and then adds in nearly all of the advanced visual technologies that we've been incubating over the past seven years, including varifocal and eye tracking."

At this stage, though, it's just a design concept and hasn't been built. Indeed, it might not get built at all; Meta says it's only one of several potential pathways to a fully integrated visual-Turing-test-capable headset.

Addressing the "why?"

"The goal of all this work," says Zuckerberg, "is to identify which technical paths are going to allow us to meaningfully improve in ways that start to approach the visual realism that we need. And if we can make enough progress on retinal resolution, and if we can build proper systems for focal depth, and if we can reduce optical distortion and dramatically increase vividness, then we have a real shot overall at creating displays that can do justice to all of the beauty and complexity of physical environments."

Meta is, of course, all-in on VR and the nebulous concept of the metaverse. And this roundtable, like the last time the company opened up its Reality Labs to talk about nerve-hijacking wrist controllers, was a fascinating opportunity to glimpse Zuckerberg and his team nerding out on the incredibly difficult problems they're trying to solve – even if it's very much a public-facing exercise. It's always a pleasure to see engineers and experts bringing the future forward, and there's a real excitement in this team; they know they're in the perfect place to do things that have never been done before, with a dream budget and a CEO that's fully invested in making this happen.

And as engineers, they must continue to focus on making this gear better. Such is the way of the engineer. But for a different perspective, I think it's worth reiterating that the Quest and Quest 2 are already devices capable of delivering a staggering sense of immersion. Sure, the graphics are a bit chunky, but I'd argue that's not what's holding VR back at this point.

The roadblocks to today's users are still content and queasiness. Truly great VR content is out there, but there's only so many times you can float in space looking at the magnificence of the Earth, or sit in the front row at an MMA fight, or play stand-and-deliver games like SuperHot and Beat Saber, before the awe of the virtual environment wears off.

And other games, that put you in the driver's seat of a spaceship, or let you walk around using a thumbstick like you would on a console, make some folk, myself included, feel nauseous when proprioception doesn't match what your brain believes is happening. Your mind tells you you're accelerating forward, but your body's not on the same page. You begin to sweat, your hands get clammy, and before too long you've got to take the headset off and get a drink of water to settle your guts.

Now, perhaps this is something you can get used to. Maybe it's as simple as popping a carsickness tablet, wearing an acupressure wristband, smoking some cannabis or simply believing it won't happen – some commonly suggested solutions. Meta is also hopeful that its varifocal technology can ease the quease in future VR, having achieved some promising results in their 2017 varifocal study. Or perhaps the social aspect of the metaverse, an advanced form of telepresence that Meta is pushing hard, will be a compelling enough reason to log in.

My point is simply that, as with console games, the quality of the graphics is only one slice of the pie. The experiences need to justify putting on a set of goggles and stepping into VR. And while it's not exactly Meta's job as a hardware manufacturer to focus on that stuff, I'd expect unmissable content to have a greater impact than true-to-life visuals on the future of this space. And it's worth remembering that it's harder to develop and optimize content with extremely high-res, realistic visuals than it is to develop for simpler systems.

Enjoy Zuckerberg and Abrash's presentation on Meta's quest to pass the visual Turing test below.

Source: Meta